André Breton: Surrealism, Dada and the Abstract Expressionists

by Gary Comenas

Page 1

to page 2

to page 3

When Time magazine reviewed the "Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in 1936, they described André Breton, the "founder" of Surrealism, as someone "who frequently dresses entirely in green, smokes a green pipe, drinks a green liqueur and has a sound of knowledge of Freudian psychology." (MF)

Although Breton did have a predilection for the colour green - art dealer Julien Levy later recalled that Breton "never removed his green jacket and vest" (MA273) - he had not actually been to the United States by the time of MoMA's exhibition and Time magazine's description of him. The founder of Surrealism arrived in the U.S. in the summer of 1941 - one of the later arrivals of a group of European artists aligned to the Surrealist movement who immigrated to the U.S. during World War II. Wolfgang Paalen, Kurt Seligmann, Matta (née Roberto Sebastian Antonio Matta Echaurren) and Yves Tanguy had all arrived two years prior to Breton - in 1939. (Paalen would move from the U.S. to Mexico the same year that he arrived. (WC)) In 1940 Gordon Onslow Ford and Kurt Seligmann arrived. Breton, André Masson, Max Ernst (accompanied by his wife-to-be Peggy Guggenheim) all arrived in 1941. Marcel Duchamp arrived in 1942 (MD). (It was Duchamp's seventh stay in the U.S. - a dated list of his U.S. trips prior to 1942 can be found at here).

THE EMERGENCY RESCUE COMMITTEE

Breton and other emigrating artists were helped by the Emergency Rescue Committee (sometimes referred to as the American Rescue Committee) in Marseilles - an organization that had been set up in the U.S. with financial contributions from private individuals in order to rescue cultural and political refugees threatened by Hitler's advance into Europe. Varian Fry, a Harvard educated Quaker, arrived in Marseilles during the summer of 1940 to oversee their operations in France - the same summer that the German forces occupied the country. (SS116) At the time of the occupation Breton was enlisted in the French Army. On September 16, 1939 he had written a letter of introduction on behalf on Wolfgang Paalen to Leon Trotsky's secretary in Mexico in which he noted that he (Breton) would soon be in uniform as part of a medical staff attached to a pilot training school near Poitiers. (SS66/7). By August 1940 Breton was in the city of Salon having traveled there after being demobilized in Gironde. On August 10, 1940 he wrote to Kurt Seligmann in New York from Salon suggesting that he (Breton) give a series of lectures in New York in order to obtain an exit visa from France. (SS114/5) He then left Salon and moved south to Montargis temporarily (where he wrote Plein Marge) before making his way to Marseille where he joined Varian Fry and other artists attempting to leave France. (FR/SS119)

The Emergency Rescue Committee office in Marseilles - L to R: Max Ernst, Jacqueline (Lamba) Breton,

André Masson, André Breton and Varian Fry (in glasses)

(Photographer: Ylla)

On December 3, 1940 Breton, who had been a member of the French Communist Party from 1927 - 1935, was arrested in Marseilles and held for four days. Vichy premier Henri Philippe Pétain was due to visit the city the next day. The official report on Breton described him as a "dangerous anarchist sought for a long time by the French police." In February - March 1941 the publication of two works by Breton - the Anthologie de l'Humeur Noir and his poem Fata Morgana were banned by the Vichy government. Breton finally left France, accompanied by his wife, Jacqueline Lamba, and their child on a transatlantic steamer which departed from Marseilles on March 24, 1941. (FR) One of his fellow passengers on the ship was the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Claude Lévi-Strauss:

"The scum, as the gendarmes described us, included among others André Breton... Breton, by no means at his ease in such a situation, would amble up and down the rare empty spaces on deck, looking like a blue bear in his velvety jacket. We were to become firm friends in the course of an exchange of letters which we kept up throughout our interminable journey; their subject was the relation between aesthetic beauty and absolute originality." (FR)

When the ship reached the port of the Fort-de-France in Martinique after about a month at sea, Breton was sent to a concentration camp in Lazaret by the Vichy authorities in Martinique who had been warned about the "dangerous agitator." Although he was released a few days later he remained under surveillance during the three weeks he stayed on the island. (FR) On April 30th André Masson arrived at Fort-de-France from Marseilles. (Masson would contribute both text and illustrations to Breton's book Martinique: Snake Charmer.)

André Masson [from La Mémoire du monde (1974)]:

"One day, while strolling on the island's Atlantic coast, where the lianas in bloom blended with the foam of the ocean waves, Breton, to my great astonishment, spoke to me of Paradise. Not that of the theologians... No, a true Paradise, here on Earth... Reviewing the paradisiacal utopians, we went from the famous 'withering away of the state' to the 'end of History,' lingering long over Charles Fourier, whom I have always called the Douanier Rousseau of socialism." [Breton's Ode à Charles Fourier would be published in c. 1947]. (FR)

Breton and his wife finally left Martinique on May 16, 1941, arriving in New York in June after a brief stop in the Dominican Republic where they visited the Spanish Surrealist Eugenio F. Granell. (FR) On June 24, 1941 Breton's wife wrote a letter of thanks to Varian Fry for helping them get out of France, describing America as "the Christmas tree of the world." (SS140) (Unknown to the Bretons at the time was the fact that throughout their stay in the U.S. they were kept under close watch by the F.B.I. (FR))

Breton would live in the United States for about 4 1/2 years, returning to France in about May of 1946. (From December 1945 to March 1946 he visited Haiti, Martinique and the Dominican Republic). (FR) It was a time in New York when, according writer Robert Lebel, "everybody met everybody. The influence was collective and this is how it spread. Each one met someone through another one. The Reises had a party at least once a month; everyone met at Peggy Guggenheim's parties - Pollock, Baziotes, and Rothko... Later the Americans hid their Surrealist paintings, but when we saw Pollock during the war he was like a little boy in front of Max Ernst." (SS197)

The "Reises" were New York accountant Bernard Reis and his wife, Becky. Bernard was the accountant and treasurer of VVV, the magazine that Breton produced during his stay in the U.S. (HH477) Reis would later act as a advisor to Abstract Expressionists Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell and Mark Rothko and also advised Peggy Guggenheim as she went about opening a gallery to house her art collection. Guggenheim and her lover, the Surrealist Max Ernst, arrived in New York about a month after Breton but, unlike Breton, traveled by air on a luxurious Pan Am Clipper plane just two years after its maiden transatlantic voyage. (Guggenheim and Ernst would marry later in the year in Virginia.) In January 1942 Breton contributed an essay on Surrealism to Guggenheim's catalogue of her collection and came up with the idea of including photographs of the eyes of the artists whose work was included in the collection to accompany their biographies in the catalogue. (MD223) Originally Guggenheim hoped to open a nonprofit museum to house her collection but Bernard Reis suggested that she add a 'for-profit' element (a gallery) from which she would be able to deduct expenses. (MD224) She opened her Surrealist art gallery, Art of This Century on October 20, 1942.

TRUTH AND AUTOMATISM

At the Reis' frequent gatherings Breton would often lead the guests in a game of Truth in which they were expected to answer personal questions (often about sex), with complete honesty. (MD224) The game was treated seriously. Violators of the rules were fined. (MD224) In addition to Breton, artists who attended the Reis' parties included Kurt Seligmann, Max Ernst, André Masson, Arshile Gorky, David Hare, Fernand Léger, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Pavel Tchelitchew and Matta. Matta, an on-again off-again follower of Breton, held his own gatherings of artists where Surrealist techniques such as automatism would be explored.

Matta:

"Automatism is a method of reading 'live' the actual function of thinking at the same speed as the matter we are thinking about; to read at the speed of events, to grasp unconscious material functioning in our memory with the tools at our disposal, with the language we possess, if possible grasping instantly, all at once, one and once make it. Automatism means that both the irrational and the rational are running parallel and can send sparks into each other and light the common road... Automatism is purposeless on purpose." (PF6-7)

Artists who gathered at Matta's studio to explore automatism included Robert Motherwell, and (briefly) Jackson Pollock.

Irving Sandler [art writer]:

"Matta had a perverse love-hate attitude toward André Breton and his coterie. Bob [Robert Motherwell] recalled: 'Matta wanted to show them up as middle-aged, gray-haired men who weren't zeroed into contemporary reality.' ... Matta then tried to put together a group of young artists who would be daring in their exploration of automatism... At first he enlisted Esteban Francis, Gordon Onslow-Ford, and Bob. But he wanted more New Yorkers in his group, and he asked Baziotes, whom he recently met, to recommend artists he knew on the Federal Art Project. Baziotes suggested Pollock, de Kooning, Peter Busa, and Gerome Kamrowski. Baziotes and Bob visited them, and Bob 'taught' them the theory of automatism, or so he claimed. De Kooning was not interested in the surrealist 'adventure,' but Pollock, who drank through the meeting, liked the idea, although he would not join a group. Then Matta capriciously gave the whole thing up. Only Arshile Gorky was accepted into the Surrealist inner circle." (IS90)

Jackson Pollock, William Baziotes, and Gerome Kamrowski produced several collaborative works around 1940/41 in which they experimented with an 'automatic' technique of painting.

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

"One evening in the winter of 1940-41, [William] Baziotes brought Jackson Pollock over to [Gerome] Kamrowski's studio, and the three artists began experimenting with quick-drying lacquer paint that Baziotes had bought at Arthur Brown's art supply store. They spread some cheap canvases out on the floor and began brushing and then dripping the paint onto them. In the process of 'fooling around,' as Kamrowski called it, they all worked on the same canvases and during the course of the evening produced a number of collaborative spontaneous works. All three artists already had some knowledge of Surrealism and were familiar with the concept of 'pure psychic automatism,' and they were trying to find ways in which the new quick-drying paint developed for commercial use could be put to this end. When Kamrowski moved out of that studio... he threw out most of these experimental canvases but kept one as a kind of souvenir, and this three-man canvas [Collaborative Painting] has surfaced in a number of recent exhibitions as a kind of proto-abstract expressionist work. Although each artist made use of dripped paint and a gestural approach in combination with other techniques during the next few years, it wasn't until 1946 that dripping lacquer began to be the basis for an entire painting and that Pollock reached what Kamrowski referred to as 'his greater freedoms.'" (SS169)

DADA

The result of automatic painting or drawing was visual images arranged randomly, by chance - a concept which had previously been explored by the Dada movement which Breton had been involved with prior to founding Surrealism. Dadaist Jean (Hans) Arp had produced a series of collages in 1916 whose elements were arranged by chance. (TJ23)

Georges Hugnet [from The Dada Spirit in Painting (1932/34)]:

"... it seems fitting to mention some of Arp's experiments which were of far-reaching importance because they were in line with activities that were later to play a large part in the theory of prospecting in the land of the unconscious. Each morning, whether inspired or not, Arp repeated the same drawing, and so obtained a series showing variations which indicated the curves of automatism. He also experimented with chance, putting on a piece of cardboard pieces of paper that he had cut out at random and then coloured; he placed the scraps coloured side down and then shook the cardboard; finally he would paste them to the cardboard just as they had fallen." (RD134)

Arp's collages were "Untitled" but subtitled "According to the Laws of Chance." Arp later wrote that the "law of chance which comprises all other laws and surpasses our understanding... can be experienced only in a total surrender to the unconscious." (LZ37)

Three years before Arp's collages, Marcel Duchamp had created Three Standard Need Weavings (1913) using a similar random technique.

Georges Hugnet [from The Dada Spirit in Painting (1932/34)]:

"This was the experiment: Duchamp took three threads, each a meter long, and these he let drop successively, from a height of one meter, on three virgin canvases. He then scrupulously preserved the contour of the fallen threads, fixing them with a little varnish; the result was a dessin du hasard, a chance design or drawing... Again and again we encounter Duchamp, both in Paris and New York, and in Picabia and Man Ray, this obsession, in various forms, with the laws of chance..."(RD140)

André Breton, as a writer and poet, experimented with automatism through automatic writing. In May/June 1919 He produced, in collaboration with Philippe Soupault, a text written 'automatically' titled Les Champs magnétiques. (WB) In The Dada Spirit in Painting, Hugnet noted the influence of Breton's use of written automatism on visual automatism when referring to the Surrealist Max Ernst: "The works of Max Ernst, collages or imaginary paintings, based on technical inventions that are a pictorial application of automatic techniques similar to those used by Breton and Soupault in their book, Les Champs magnétiques, bring to Dada painting a new and very personal vision which foreshadows Surrealism." (RD178) Les Champs magnétiques was first published in Breton's Littérature magazine, a Dada- friendly journal published from 1919 to1924 in France. (The first issue was February 1919.) (HB/WB)

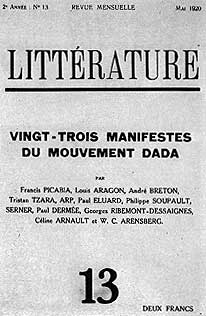

Cover of Littérature, vol. 2 no. 13, Paris 1920 edited by Louis Aragon, André Breton and Philippe Soupault

Georges Hugnet [from The Dada Spirit in Painting (1932/34)]:

"Louis Aragon, André Breton and Philippe Soupault were contributors to various advance guard magazines, among others Sic... In 1919 they founded Littérature... These men, whom we shall call the 'Littérature group,' represented a poetic and critical position between Rimbaud and Lautreamont on the one hand and Jarry and Apollinaire on the other; they supported the effort to liberate the mind in progress since the second half of the nineteenth century... they were immediately attracted to the activity proposed by Dada... they saluted Dada, a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the post-war economic and moral crisis, a savior, a monster, which would lay waste everything in its path. They felt that it would be an offensive weapon of the first order. Thus, through the word Surréalisme, borrowed from Apollinaire and already full of meaning, was regularly used by the Littérature group and their friends, their magazine, for want of an alternative course at the moment, gave itself to Dada, a scarecrow erected at the crossroads of the epoch." (RD165/167)

TRISTAN TZARA

Although Breton initially embraced Dada and would borrow from it for Surrealism, his relationship with the movement became strained after the arrival in Paris at the end of 1919 of one of Dada's founders, Tristan Tzara (born Samuel Rosenstock on April 16, 1896 in Moinesti, Romania). Tzara edited his own Dada magazine, simply titled Dada, in Zurich (the first issue was July 1917 (RD34)) and also contributed to Breton's Littérature magazine beginning with the second issue. One of the first Dada events that Tristan participated in after arriving in Paris was organized by Breton and the Littérature group - the "Premier Vendredi de Littérature" which took place on January 23, 1920 at the Palais des Fêtes. Tzara promised to read a new manifesto at the event but instead read a newspaper article. According to Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes in History of Dada (1931), "when Tzara, after announcing a manifesto, merely read a vulgar article taken out of some newspaper, while the poet Paul Eluard and Theodore Fraenkel, a friend of Breton, hammered on bells, the public began to grow indignant and the matinée ended in an uproar." (RD109) The uproar included cries of "Back to Zurich!" from the audience. (DC441) During another event, the Dada Festival, which took place on May 26, 1920 at the Salle Gaveau, Tzara couldn't get his "Vaseline symphonique" to work. Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes recalled about the "symphonique" - "though scarcely very musical, it encountered the open hostility of André Breton, who had a horror of music and suffered from being reduced to the role of an interpreter." (RD111)

The "open hostility" of Breton mentioned by Ribemont-Dessaignes may also have had something to do with an insulting unsigned letter Tzara received prior to the Festival which was suspected to be from Breton or the Littérature group.

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes [from History of Dada (1931)]:

"It was also at Picabia's, between the Maison de l'Oeuvre Dada demonstration [March 27, 1920] and the next [the Dada Festival on May 26, 1920], that we experienced the repercussions of a strange event known in the Dada archives as the 'affair of the Anonymous Letter.' Tristan Tzara had received a highly insulting unsigned letter, and its terminology led one to suspect that it had been written by either one of the Dadaists or one of their close enemies. Through application of the Hegelian-Dadaist dialectic, we came successively to the conclusion that the letter had been written by one of the members of the Littérature group, by Breton or Aragon, or possibly even by Philippe Soupault, Theodore Fraenkel or Francis Picabia, or, finally, by Tristan Tzara, who perhaps had written the letter to himself in order to foster demoralizing suspicion amid his own group." (RD111)

The relationship between Tristan Tzara and Breton's group of Dadaists became strained even further after negative comments made by Tzara during a mock Dada trial organized by Breton in 1921 and Tzara's failure to endorse a Dada congress which Breton attempted to organize not long after the trial. The "Trial and Sentencing of M. Maurice Barrés by Dada," took place at the Salle des Societies Savantes in the Rue Danton on Friday evening, May 13, 1921. (RD116) Maurice Barrés was a liberal writer who, during World War 1, became a staunch nationalist. Breton set himself up as judge for the mock trial and published the proceedings in Littérature. (PJ354)

Georges Hugnet [from The Dada Spirit in Painting (1932/34)]:

"The Littérature group put on the most subversive meeting, from the moral point of view, in which Dada had ever been involved. The 'Barrès trial' forced Dada to take a position on several concrete questions. On Friday, May 13, [1921] in the Hall of Learned Societies, Maurice Barrès was "indicted and tried by Dada." André Breton, president of the tribunal, had drawn up a stern and scathing indictment... In announcing the verdict, Breton declared 'Dada, judging that the time has come to endow its negative spirit with executive powers, and determined above all to exercise these powers against those who threaten its dictatorship, is beginning, as of this date, to take appropriate measures.... Dada accuses Maurice Barrès of offense against the security of the spirit.' ... The tone of the verdict is somewhat different from that of the usual Dada writing... Practically speaking, the result of the new extravaganza was general dismay, expressed, as far as the critics were concerned, in a threat never again to mention Dada in their columns. Once again Dada had been unable to reply categorically: the role of judge did not suit it at all." (RD184-5)

Although Tzara participated in the trial he used his testimony to attack it, declaring "I have no confidence in justice, even if this justice is made by Dada." He referred to both the accusers and the accused as "a bunch of bastards... greater or lesser bastards is of no importance." (PJ354) When Breton attempted to get Tzara's support for his idea of a Congress of Paris (with Breton as the director), Tzara refused to get involved. (The initial committee for the Congress consisted of seven people - Breton, Georges Auric, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay, Amédée Ozenfant, Jean Paulhan and Roger Vitrac.) (PJ372fn69)

Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes [from History of Dada, 1931]:

"Breton's personal reactions led him to conceive of a grandiose undertaking in which he would have played the leading role. This was to be a super-congress of all intellectuals wielding influence on the state of the modern mind, in order to determine what was modern and what was not, in short, a grand congress of the mind... But the Dadas were not in agreement. Tristan Tzara, in particular, supported by Ribemont-Dessaignes, raised numerous objections because of the dogmatic aspect such an undertaking would assume... With him Paul Eluard, Theodore Fraenkel, Ribemont-Dessaignes and Erik Satie withdrew. But the publicity which the Congress of Paris had received prevented Breton from retreating. So he persisted and, despite the defection of the greater part of Dada - it is true that he had the support of Picabia who had become anti-Dada - he continued his work as director of the Congress. But new difficulties arose, and certain members of the committee resigned. To add to all this the poet Roger Vitrac, head of Aventure magazine, on which Breton counted heavily, fell ill. This finally discouraged Breton: he abandoned the undertaking on which he had so set his heart.

The bitterness Breton felt led him to cast the main responsibility for the failure on Tristan Tzara and to indulge in open vengeance. He published in Comoedia several articles in which, scorning Dada amorality, he adopted a bourgeois point of view toward Tzara's conduct. He specifically accused Tzara of not being the father of Dada and of having defrauded Serner by claiming authorship of the Dadaist Manifesto of 1918... In writing of Tzara, he used pejoratively such terms as 'arrived from Zurich,' just as Picabia had called him a 'Jew'... Finally, he called Tzara a publicity-mad imposter, and concluded with a pathetic appeal in favour of himself who 'proposed to consecrate his life to ideas.'" (RD119)

Page 1

to page 2

to page 3