Abstract Expressionism 1941

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

Mark Rothko: "Large pictures take you into them... I think that small pictures since the Renaissance are like novels; large pictures are like dramas in which one participates in a direct way."

1941: Essays on a Science of Mythology by Carl Jung and Karl (Károly) Kerényi is published.

1941: Richard Pousette-Dart paints Symphony No. 1, the Transcendental.

The work measured 90 x 120 inches. (approx. 3 ft. high and 10 ft. length) At the time that Pousette Dart created his ten foot painting "other painters shook their heads over the futility of working on such a scale unless it was a commissioned work," according to Martica Sawin in Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995) . (SS372)

Abstract Expressionist canvases became increasingly larger. Jackson Pollock's canvases from 1942, for instance, are much larger than his previous work. Male and Female is a six foot high vertical canvas. The Moon Woman is just under six feet and Stenographic Figure, a horizontal painting, is about 5 1/2 feet long. (JP125) Eventually the canvas would be extended into the room with the installations of Red Grooms, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg during the late fifties/sixties.

Mark Rothko [Pratt Institute lecture 1958]:

Large pictures take you into them. Scale is of tremendous importance to me - human scale. Feelings have different weights; I prefer the weight of Mozart to Beethoven because of Mozart's wit and irony and I like his scale. Beethoven has a farmyard wit. How can a man be ponderable without being heroic? This is my problem. My pictures are involved with these human values. This is always what I think about... I think that small pictures since the Renaissance are like novels; large pictures are like dramas in which one participates in a direct way. The different subject necessitates different means. (RO396)

c. Late 1940/Early January 1941: Mark Rothko and his wife move to mid-town. (RO153)

Mark Rothko and Edith were living in their new mid-town apartment by early January 1941. Milton Avery referred to their new apartment as "a nice big apartment" that was "really swell" in a letter dated January 13, 1941. Their new apartment was on 28th Street near Fifth Avenue. Presumably, Edith's successful jewelry business was their main source of income at the time. (RO153)

After Rothko and Edith temporarily separated in 1940, Rothko returned to live with his wife and to work for her jewelry business. Edith had the front part of the loft as her jewelry workshop and Rothko painted in the back. According to their friend, Sally Avery (wife to Milton Avery), Edith "didn't want him [Rothko] to paint because he didn't sell anything." (RO170)

January 1941: Franz Kline moves again.

Franz Kline and Elizabeth moved from 71 West 3rd Street to 430 Hudson Street (second floor). (FK176)

January 22 - April 27, 1941: "Indian Art of the United States" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

Jackson Pollock attended the exhibition and watched Navajo artists doing sand paintings on floor of the gallery. (PP319)

Late January 1941 - March 1941: A series of four lectures on Surrealism are given at the New School for Social Research by Gordon Onslow Ford.

Among the people who attended Ford's lectures were Matta, William Baziotes, David Hare, Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage, Robert Motherwell, Frederick Kiesler, Nicolas Calas, Jimmy Ernst, Robert Lebel and, according to some accounts, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Arshile Gorky. (According to Onslow Ford, Gorky was a regular visitor to his Eighth Street apartment). (SS158)

From the flyer for the lecture series:

Surrealist Painting: an adventure into Human Consciousness; 4 sessions, alternate Wednesdays, 8:20 to 10 p.m. $4. Far more than other modern artists, the Surrealists have adventured in tapping the unconscious psychic world. The aim of these lectures is to follow their work as a psychological barometer registering the desire and impulses of the community. (SS156)

The lectures were accompanied by small exhibitions in an adjacent room at the New School, hung with the help of Howard Putzel. The first exhibition opened on January 22 and was devoted to Giorgio De Chirico. Following that was an exhibition of ten paintings by Max Ernst and Miro on February 5th. The exhibition for the February 19th lecture was devoted to Magritte and Tanguy. The fourth exhibition, hung for the March 5th lecture, was a group show of Surrealist painting during the last four years and included works by Delvaux, Brauner, Paalen, Seligmann, Matta, Onslow Ford, Jimmy Ernst and Esteban Frances. A garbage can with "Dali" written on it was by the front door. (SS157)

Concluding remarks from the March 5th lecture:

Tonight I have given you a brief glimpse of the works of the young painters who were members of the Surrealist group in Paris at the outbreak of the war. Perhaps it is not be chance that all of us except Brauner and Dominguez have managed to find our way to these shores... I am overjoyed to tell you that I hope soon André Breton will be with us and that Pierre Mabille has got as far as Martinique and will come here the moment it appears possible for him to make a living. I think I can speak for all my friends when I say that we are completely confident in our work and slowly but surely with the collaboration of the young Americans we hope to make a vital contribution to the transformation of the world. (SS165-6)

Jimmy Ernst:

One evening at the Jumble Shop after one of Gordon Onslow Ford's lectures we were all sitting around. Matta and Gorky were there. Gorky didn't have much use for Matta personally and they were always at each other's throat, particularly since Gorky then was seemingly heavily influenced by Matta in his approach. Matta, referring to a prior visit to Gorky's studio, said "There's something in the upper right-hand corner of the last painting - how did you do that?..." Gorky said, "Well, first you take a glass or a palette and you squeeze paint on that, then you have brushes, then you have a little cup with turpentine and some oil. You dip the brush in the cup and in the paint and you transfer it to the canvas." Matta said, "Yes, but how did you do it?" "That's how I did," said Gorky. (SS167)

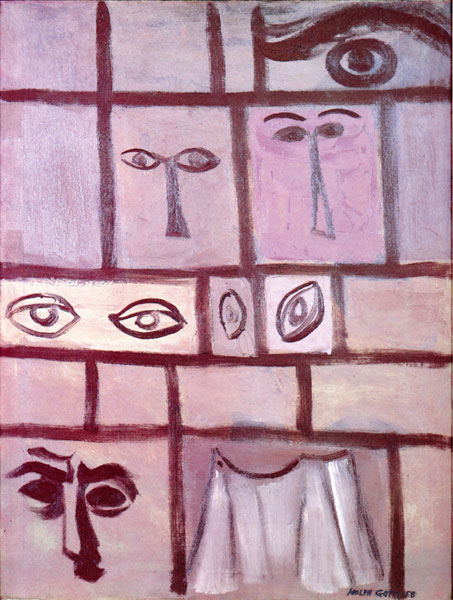

1941: Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko paint myths.

According to Adolph Gottlieb he and Rothko adopted mythological themes after a discussion they had in 1941. Gottlieb later recalled saying to Rothko, "'How about some classical subject matter like mythological themes?' And we agreed... Mark chose to do some themes from the plays of Aeschylus, and I played around with the Oedipus myth, which was both a classical theme and a Freudian theme." (AG35)

According to Barnett Newman, the subject of myths was brought up after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (see below). Newman recalled that after the attack he commented to Adolph Gottlieb that "painting was finished" and that it was Gottlieb "who first broached the idea that we needed a new subject matter ... We respected the Surrealists but disagreed with their Marxist and Freudian approaches. Our orientation was more mythic. Gottlieb and I looked to primitive art. Our interest was in breaking out of art history as we knew it." (IS286)

Mary Davis Mac Naughton ("The Pictographs" in Adolph Gottlieb: A Retrospective (NY: The Arts Publisher, Inc., 1981):

Gottlieb arrived at myth in 1941 in various ways. He may have noticed [John] Graham's mythological titles like "Zeus" on paintings in a one-man show in the spring of 1941 at the Artists Gallery. But it was undoubtedly through reading Freud that he focused specifically on the Oedipus myth, to which he alluded in several works of the early forties, including Oedipus and Eyes of Oedipus of 1941, Oedipus Pictograph Totem of 1942, Hands of Oedipus and Eyes of Oedipus of 1945. In 1941, as America plunged into war, Gottlieb was pulled toward the Oedipus myth because he found in it a powerful statement of man's tragic nature. Through Freud he saw Oedipus as a symbol of man's eternal conflict within himself and against society. (AG35)

Oedipus, 1941, Adolph Gottlieb, oil on canvas 34 x 26"

Although Gottlieb said that he and Rothko started painting myths after a conversation in 1941, Rothko's Antigone, probably his first painting with a mythological title, has been attributed to 1938. However, it is possible that it was painted later than that. Rothko dated most of his paintings from memory, years after painting them. The first time that Antigone was shown was in January 1942 at Macy's department store. (AG52n39)

February 1941: Arshile Gorky meets his future wife, Agnes Magruder.

They would marry less than a year later - see September 15, 1941 below. (HH321)

March 1941: The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors begins a series of annuals.

The annuals were supplemented by smaller shows including exhibitions at the Smith College Museum of Art, the Yale University Museum, the Wadsworth Antheneum, the Institute of Modern Art (Boston), the Lotus Club, the National Arts Club. (RO155)

March 1941: Twelve Jackson Pollocks are destroyed.

The Federal Art Project disposed of more than six hundred and fifty watercolours which were kept in storage by incinerating them. Among the paintings were works by Milton Avery and both Jackson and Sande Pollock. The twelve destroyed works by Jackson Pollock included Sunny Landscape, Baytime and Martha's Vineyard - paintings completed during his summers with the Bentons at Chilmark. (JP81)

March 10 - May 3, 1941 "New Acquisitions: American Painting and Sculpture" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

It included Arshile Gorky's Argula which, according to Gorky biographer, Nouritza Matossian, was "hung in a place of honour." (I am assuming this is the same exhibition that Matossian refers to as "Recent Acquisitions" and Hayden Herrera refers to as "New American Acquisitions." (BA307/HH291))

The painting was donated to the museum by Bernard Davis. According to another Gorky biographer, Hayden Herrera, "Argula (1938) is the first painting that clearly belongs to the Garden in Sochi series. For the first time the bi-lobed boot shape - which I believe is a butter churn, although it surely has other meanings as well - hangs from a vertical black line. In Khorkom, butter churns made of a goatskin were suspended from the rafters or from a wooden structure with three or four legs... Flanking the boot/butter churn in Argula are ideographic female figures... They recall the women with upraised arms in Gorky's drawing based on Picasso's Women Playing at the Edge of the Sea and they also bring to mind the sprightly female celebrants flanking a central motif in a groups of Garden in Sochi precursors from the late 1930s and early 1940s including Tracking Down Guiltless Doves and Composition." (HH290)

Matthew Spender [From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky]:

Gorky did not utter a word before he was about five years old. He had no disability as far as any of his family could tell: he was merely slow. One story has it that his uncle Krikor forced him into speech by taking him up onto the roof and telling him to jump off. His first words, then, were "No, I won't." Another story has it that a thirteen-year-old cousin tried to frighten him into speaking. Little Manuk [Gorky] took up a stick to defend himself. His cousin pretended to be wounded. He cried out, "An gu la," "He is crying." Bewildered, Gorky ran to his mother Shushan, repeating the words.

In the 1940s [attributed to 1938 by Herrera and Matossian] Gorky named a painting Argula. After this work was sold and given to the Museum of Modern Art, Gorky received a letter asking him what the title meant. He replied, "No specific scene but many incidents - The first word I spoke was Argula - it has no meaning. I was then five years old. thus I call this painting Argula as I was entering a new period closer to my instincts." (MS15)

March 25, 1941: André Breton emigrates from France.

The Bretons, the Lams and Victor Serge departed on a ship, the Capitaine Paul-LeMerle, bound for Martinique. (SS137)

Beginning of April, 1941: André Masson emigrates from France.

A week after Breton left France, Masson followed on the Carimare, a ship also bound for Martinique. During their time in Martinique Breton and Masson collaborated on a small book, Martinique: Snake Charmer. (SS136)

Masson would arrive in the U.S. in May 1941 (see below).

Spring 1941: John Graham solo exhibition at the Artists Gallery.

Included was Graham's Zeus. (AG35)

April 7, 1941: Mark Rothko complains about the Artists' Coordinating Committee at a meeting of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors.

From Mark Rothko: A Biography by James E.B. Breslin:

As the federation's representative to the Artists' Coordinating Committee, an organization of fourteen artists' societies, Rothko - "the earliest anti-Stalinist I knew," according to George Okun - actively participated in the federation's battles with the official left. In 1936 the Artists Coordinating Committee had pressured TRAP into taking on more artists (leading to Rothko's appointment), and then in 1937 had persuaded the Federal Art Project to hire artists (like Rothko) who had been terminated by TRAP. By 1941, however the committee was chaired by Hugo Gellert, a doctrinaire Marxist, author of Karl Marx's Capital in Lithographs (1933) and Comrade Gulliver (1934), whose "policy," Rothko reported at one federation meeting, "seems to be not to notify unsympathetic groups of meetings (non-communists)." "Mr Rothko objected to [Gellert's] having chosen three [symposium] speakers where 14 societies were involved. Mr. R[othko] saw to it that representatives from all 14 societies [will] come to next meeting on Monday." "Elections are constantly delayed," Rothko complained. The federation, he contended, had to decide "what to do to counteract Mr. Gellert['s] complete control" and to form "a plan to carry on [the committee's] work if we force a change in control." (RO156)

April 22 - May 19, 1941: Dali exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA307)

1941: Yves Tanguy and Kay Sage move to Woodbury, Connecticut.

A few years later they would buy a farmhouse in Connecticut in the same area that Arshile Gorky would later move to.

May Day, 1941: Arshile Gorkys' wife-to-be Agnes Magruder marches under the banner of the Chinese Communists.

According to Agnes (nicknamed Mougouch), Gorky "was very enthusiastic about my politics" and helped her to lay out a Communist magazine Agnes was working for as a volunteer - China Today - whose offices were located on 23rd Street, around the corner from Willem de Kooning's studio. (BA301/307)

May 1941: Marc Chagall emigrates from France.

Chagall escaped from the Nazis with the help of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee. He and his family arrived in Spain first (on May 7) and then LIsbon (May 11) before settling in the United States. (CL6)

May 1941 : André Masson arrives in the United States.

Upon his arrival a customs official impounded a box of drawings Masson had brought with him. The inspector was offended by a drawing in which a landscape and cave doubled as the body of a woman with a small figure entering her vagina. When the official objected Masson responded by telling him he had no mythology and the drawings were impounded.

The Massons initially stayed at the Hotel van Rensselaer on East 11th Street where he wrote a thank you letter to his patron Saidie May in Baltimore in which he commented "I think I would be dead if I had stayed there [in France]." In his letter Masson also gave his first impression of New York: "New York pleases me, but it's devouring me. I hope to live in the country." By June 22, when he wrote her again, he was living in Washington, Connecticut in a home that the Massons rented for the summer. In the autumn they stayed first with Eugene and Marie Jolas at Lake Waramaug and then rented a converted barn in New Preston for the winter. (SS140-141)

Masson returned to France in October 1945. (DB)

May 22, 1941: Jackson Pollock undergoes a psychiatric examination to determine his eligibility for military service.

On May 3, 1941, Jackson's psychoanalyst, Dr. de Lazlo, had written to the draft board that he found Pollock "to be a shut-in and inarticulate personality of good intelligence, but with a great deal of emotional instability who finds it difficult to form or maintain any kind of relationship." Although the doctor did not diagnose schizophrenia, she noted that "there is a certain schizoid disposition underlying the stability." She recommended that Pollock be given a psychiatric examination which he underwent on May 22nd at Beth Israel Hospital. During the exam he told the doctor he had been institutionalised three years earlier and the government requested proof which Dr. de Laszlo supplied. Pollock was classified 4F. (PP319/JP104-5)

Spring/Summer 1941: Robert Motherwell travels to Mexico with Matta.

The trip had originally been planned by the Seligmanns who were considering moving to Mexico. They invited Seligmann's pupils Robert Motherwell and Barbara Reis to join them. At the last minute the Seligmanns had problems with a transfer of funds from Europe and were unable to go and the Mattas went on the trip instead. While in Mexico Motherwell began painting The Little Spanish Prison and also met the artist Wolfgang Paalen. (IS90)

see Robert Motherwell, Matta and Wolfgang Paalen in Mexico

c. June 1941: André Breton arrives in the United States.

Breton and his wife left France on a boat to Martinique on March 25, 1941. They were able to get space on a ship to New York from Martinique at the end of May. Stanley William Hayter later recalled meeting the Bretons when their ship arrived in the U.S. and taking them to the sidewalk terrace of the Brevoort for a pastis. (SS139) Kay Sage had found an apartment on Eleventh Street for the Bretons. On June 24, 1941 Jacqueline Breton sent a letter of thanks to Varian Fry in Marseilles: "America is truly the Christmas tree of the world." (SS140) Fry, an American Quaker living in Marseilles, worked for the Emergency Rescue Committee which had been set up to locate leading intellectual and political refugees in order to help them escape the Nazi threat by them apply for visas, by providing them with financial assistance if required and, in some cases, providing them with a hiding place until they were able to emigrate. (SS117/183)

(Note: According to Franklin Rosemont in his introduction to the 2008 edition of Martinique: Snake Charmer, Breton arrived in "early July." However, if Jacqueline Breton wrote her thank you letter on June 24th, the Bretons must have arrived in June rather than July. )

1941: Adolph Gottlieb begins painting Pictographs.

Adolph Gottlieb:

In the forties, I was involved with an all-over sort of image in which there was no single focal point. There may have been a multiplicity of focal points. I was involved in what I call the 'pictograph,' and this consisted of frames, or irregular rectangular shapes, filling the canvas. It was all somewhat linear. The lines were drawn out at all four edges, so that there appeared to be no beginning and no end. The idea was of having disparate images juxtaposed, which would take on a meaning that was different from the isolated image by itself. (JG257-58)

see Adolph Gottlieb's Pictographs

1941: Barnett Newman and his wife move to 343 East 19th Street. (MH)

1941: Barnett Newman's wife gets a master's degree in education from New York University.

Annalee would eventually become the acting chairman of her department at Bryant High, but would later say about her teaching career, "For me it was no career. It was just a job. A job to earn a living so I could free my husband... We were two people who had a single cause." (MH)

Summer 1941: Barnett Newman and his wife take classes at Cornell University.

Barnett and Annalee attended botany and ornithology classes at the University in Ithaca, New York. (MH)

Summer 1941: Philip Guston paints Martial Memory. (MM32)

June 22, 1941: Germany invades the Soviet Union.

The invasion began at 4:00 in the morning. An hour later, Joseph Goebbels read a statement by Hitler on national radio which promised that the mobilisation of the German army would be the "greatest the world has ever seen."

June 30 - July 27, 1941: Paul Klee exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

July 7, 1941: The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors discuss "Esthetics."

The "esthetics" of a work was not linked to advancing a political message (such as the war effort) or a material goal (such as advancing one's career). It was more of a matter of art for art's sake. (RO157)

July 14, 1941: Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst arrive in the United States from Lisbon.

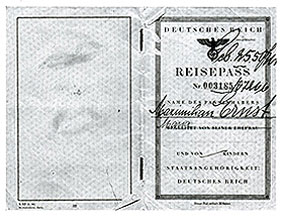

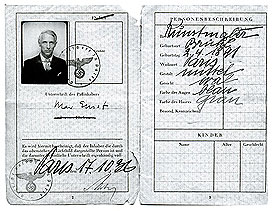

Max Ernst's passport - issued by the German Reich in Paris in 1936

Unlike the other Surrealists who arrived by ship, Guggenheim and Max Ernst arrived by plane - on a luxurious Pan Am Clipper, just two years after it made its first transatlantic flight in 1939. Beds were available for passengers and dinner was served on real china with real silver. (MD210-11)

After closing her Guggenheim Jeune gallery in England in the summer of 1939, Peggy made (unsuccessful) plans to open a museum of modern art in England with Herbert Read agreeing to work as the director of the museum. (MD185-6) Armed with a list of artists provided to her by Read she traveled to Paris to buy some art. (She crossed off some of the names of the list, including Matisse, Cézanne and Henri Rousseau, who she thought weren't modern enough. (MD187)) At a time when Europe was preparing for war she went on a buying spree. After Great Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, the plans for a museum were dropped. She hid her collection temporarily at the Musée de Grenoble and moved to Grenoble in autumn 1940. While she was in Grenoble Kay Sage (Tanguy) wired her from the U.S. asking her to "help rescue and finance" five Europeans trying to escape from France: André Breton, his wife Jacqueline Lamba, their young daughter Aube, Max Ernst and "Dr. Mabille" (Pierre Mabille) - all of whom were in Marseilles with the Emergency Rescue Committee. Peggy agreed to help all of them except Mabille. (MD205)

Peggy visited Breton and the others at Air Bel twice and ended up having a sexual relationship with Max Ernst who she would later marry in the United States. (MD208) While she was in Marseilles she was visited by a plainclothes policeman who asked if she was Jewish. She told him she was American. He asked her if her name was Jewish. She responded that her Grandfather was Swiss. He ordered her to come to the police station with him. She followed the policeman out of her room where the policeman's supervisor was waiting. The supervisor told the policeman to leave her alone. (MD209)

She left from Lisbon as Lisbon was the only European city where flights were still departing. Guggenheim and Ernst arrived at the La Guardia Marine Air Terminal on July 14 where they were met by Max's twenty-one year old son Jimmy Ernst (who was then working in The Museum of Modern Art's film department) and Gordon Onslow Ford and his wife Jacqueline. (MD211/12)

[Note: de Kooning: An American Master and the chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock gives Guggenheim's arrival date as July 13, 1941. (PP319/DK160)

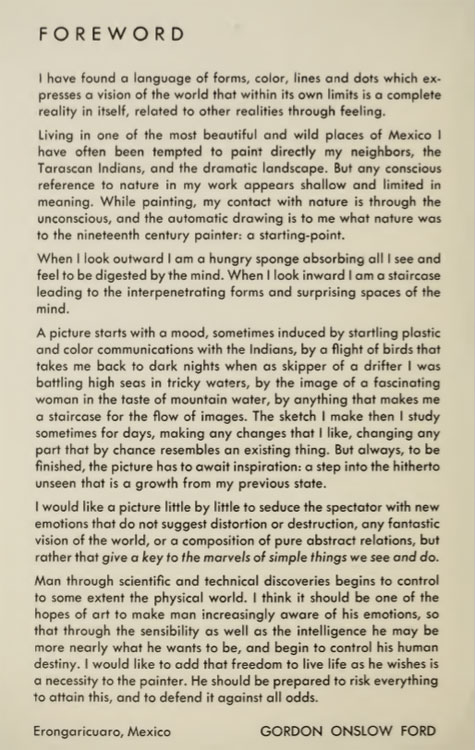

1941: Gordon Onslow Ford and Jacqueline Johnson move to Mexico.

In 1946 Ford had a solo show of his Mexican paintings at the Nierendorf Gallery at 53 East 57th Street in New York (January 22 - February 16, 1946). He explained his approach to painting and his view of Mexico in the four page brochure that accompanied the exhibition.

Gordon Onslow Ford, "Foreword," Exhibition brochure, Nierendorf Gallery, NY (January 22 - February 16, 1946)

Autumn 1941 - 1945: Philip Guston moves from Woodstock to Iowa.

Philip Guston became the Artist in Residence at the State University of Iowa. About a year a half after moving a daughter was born which Philip and his wife named Musa, the same name as his wife. (MM32-33)

August 1941: The Seligmann's stay in Londonderry, Vermont.

They had previously visited Meyer Schapiro and his family in Londonderry and returned in August to stay at a nearby guest house. (SS189)

August 9 - 24, 1941: Arshile Gorky solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

The exhibition included the following works: Portrait of My Mother (1921) (charcoal drawing), Portrait of My Sister (1923) ( oil), Torso (1926) (oil), Still Life (1929) (oil), Still Life (1929) (oil), Mougouch (1933) (pen and ink), Composition (1933) (oil), Image in Xhorkom (1934) (oil), Xhorkom (1935) (oil), Composition (1937) (oil), Head Composition (1938) (oil), Portrait (1938) (oil), Painting (1938) (oil) (lent my MoMA), Nostalgia (1939) (oil), Painting (1939) (oil), Berevano (1941) (gouache), Composition (1937) (oil), Enigmatic Combat (1937) (oil) (lent by Jeanne Reynal). (BA525/549)

The exhibition was arranged by Jeanne Reynal who met Gorky at a dinner with Margaret La Farge Osborne, a friend of Isamu Noguchi. Gorky and his wife-to-be, Agnes Magruder, went to San Francisco in advance of the show's opening - driven cross-country by Noguchi. In order to pay for the journey, Gorky approached Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art and asked if she knew anyone who would buy a painting. She bought one herself, paying for it in two installments of $75. (BA309) Jeanne had promised Gorky that he could stay at her boyfriend's farm. According to a letter that Gorky sent to his sister Vartoosh, Reynal purchased a Gorky painting for $500 and "she invited all of us to go and paint there this summer."

In the same letter Gorky also mentions unsuccessfully approaching his early patron Mrs. Metzger for funds: "As you know, my acquaintances here will pay no more than $25 or $50 for my paintings so that when I sell a painting I am unable to paint another one with this money because supplies are so expensive. Two weeks ago I approached Mrs. Metzger, who for 14 years has been waiting to buy a painting, and when I explained to her my pronounced need for money, she replied, 'We are all in a similar situation.'" (BA308)

The drive to San Francisco was a long one and Gorky wasn't particularly impressed by middle America. At one point, while they were driving over a Bridge crossing the Mississippi, he told Noguchi to stop the car and started to walk back to New York. He was also not very keen on the food he ate at the American diners en-route . Looking at canned soup and the waitress serving it, Gorky asked "How come these girls know how to paint their faces so well, but they can't make a soup?" About the other food being served he commented, "They fry everything but the ice-cream." (BA309)

Once they got to San Francisco, they learned that Reynal had split up with her boyfriend so staying on his farm was out of the question. Gorky wrote to Vartoosh on July 20, 1941 that "in all my life I had never before made such an error. It appears that my friends wanted me along for the purpose of reducing their traveling costs." (BA310)

While in San Francisco, Agnes discovered she was pregnant. Gorky was overjoyed, saying that they could get married and have the child but Agnes did not want to get married under those circumstances. She decided on an abortion and managed to get the name and address of a doctor who could give her one in San Francisco. Abortion was still illegal in California. (BA311)

After the abortion Gorky became depressed. According to his friend, John Ferren, who had shown up in San Francisco after a hiking trip in the Sierras with Kenneth Roxroth, Gorky "seemed very depressed... He seemed very disturbed, upset about something." Agnes regretted her decision, later saying that Gorky "always wanted to have a child and I'm very sorry I didn't just have it, and wasn't so stubborn about myself. In a funny way, I wasn't in love with him [Gorky], I just loved him." According to Jeanne Reynal, Gorky didn't paint for "three months" with the exception of gouache he painted for her to use as a design for a mosaic. (BA311)

Things gradually improved in San Francisco as Gorky was introduced to more people there. He became friendly with Fernand Léger who was teaching at nearby Mills College and also befriended the Russian architect Serge Chermayeff. (BA312) He wrote to Vartoosh, "Since my last letter, which was so discouraging, everything appears to have improved. I have met many people who in turn have introduced me to lots of others..." At the end of the letter he asked his sister and her husband, "Vartoosh dear, by the way what do you think about this war and how do things look in the Soviet Union? I ask both of you to give me your views." (BA311)

Gorky and Agnes stayed in San Francisco for about three months - from c. July 1941 - September 1941. (Letters to Vartoosh from Gorky in San Francisco are dated July and Gorky and Agnes drove to Chicago at end of September. (BA314/317))

August 10, 1941: A letter by Samuel Kootz is published in The New York Times about the future of American painting: "we are on our own."

Samuel Kootz [from the letter]:

Under present circumstances the probability is that the future of painting lies in America... We can expect no help from abroad today to guide our painters into new paths, fresh ideas. We have them hermetically sealed by war against Parisian sponsorship - that leadership we have followed so readily in the past - we are on our own... I probably have haunted the galleries during the last decade as much as have the critics... My report is sad. I have not discovered one bright white hope... Subject matter, that's the only thing the galleries are showing... True, some years ago, we had a rash of class-struggle painting, but the boys didn't have their ideas straight, and they killed what they had by shamelessly putting those ideas in the same old frames - they made no effort to invent new techniques to express their thoughts... Yet no new talent has come forward to challenge them... now is the time to experiment. You've complained for years about the Frenchmen's stealing the American market - well things are on the up and up. Galleries need fresh talent, new ideas. Money can be heard crinkling throughout the land. And all you have to do, boys and girls, is get a new approach, do some delving for a change - God knows you've have time to rest. (SG65)

August 22, 1941: An article appears in the New York Sun with Gorky's comments about his Riviera Club murals.

According to Gorky biographer, Matthew Spender, "after the summer [of 1940], Willie Muschenheim at last landed him [Gorky] a mural commission, at a new club in Fort Lee, New Jersey, owned by a man called Ben Marden." (MS198-9) A reproduction of an abstract mural design by Gorky for Marden's Riviera Club in Fort Lee is published in Spender's book, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky with the date of 1940. (HH199) According to Nouritza Matossian, "in the winter of 1941 Gorky traveled each morning to Fort Lee in New Jersey to work on the mural." (BA295) According to Hayden Herrera, "through Noguchi and Willie Muschenheim, Gorky was commissioned in fall 1940 to paint murals for nightclub impresario Ben Marden's Riviera Club..." (HH314).

According to Matossian, Gorky wrote to his sister, Vartoosh on December 28, 1941: "As you know I was going to do a relatively large mural painting for the architect here, and he liked it very much. But the architect wrote to me that due to the war situation. Mr Marden wants to wait several months to see what conditions here will be. Frankly, I worked an exceedingly long time on those pictures, that is the sketches, but what can one do? Actually, I toiled on them for two months and now a few words turn everything topsy-turvey." (BA319)

The letter to Vartoosh gives the impression that the murals were not finished by the end of 1941 and that he had toiled on them for "two months." If he received the commission in the fall of 1940, it seems unusual that they remained unfinished by the end of 1941 and that Gorky had only worked on them for "two months" during that period. He does not say in his letter to Vartoosh that he has been working on them for more than a year. On August 22, 1941, The New York Sun published an article on the murals with comments by Gorky which give the impression that they were finished by that time:

Arshile Gorky [from Malcolm Johnson, "Cafe Life in New York: The New Murals at Ben Marden's Riviera as the Artist Sees Them," New York Sun, August 22, 1941]:

I call these murals non-objective art, but if labels are needed this art may be termed surrealistic, although it functions as design and decoration. The murals have continuity of theme. The theme - visions of the sky and river. The coloring likewise is derived from this and the whole design is contrived to related to the very architecture of the building.

I might add that though the various forms all had specific meanings to me, it is the spectator's privilege to find his own meaning here. I feel that they will relate to or parallel mine.

Of course the outward aspect of my murals seemingly does not relate to the average man's experience. But this is an illusion! What man has not stopped at twilight and on observing the distorted shape of his elongated shadow conjured up strange and moving and often fantastic fancies from it? Certainly we all dream and in this common denominator of everyone's experience I have been able to find a language for all to understand. (HH317)

Ben Marden's Riviera nightclub (and what remained of the murals) was torn down during the 1950s. (HH317)

September 1941: Art by soldiers in Army Camps at Contemporary Arts. (SJ)

September 15, 1941: Arshile Gorky marries Agnes Magruder.

They were married in Virginia City, Nevada during their trip to San Francisco. (BA549) His new wife's family owned a farm in Virginia where Gorky and Agnes would spend the summer of 1943. In 1944 they moved there for nine months. Then, after returning to New York for two months, they lived temporarily in a home in Connecticut owned by David Hare. (DK210-11)

Arshile Gorky [from a letter to Agnes]:

I am blessed in being able to love you, blessed be the day when the great sun guided me to you. Without you, love, I should have been flung into an outer darkness, where bones rot, and where man is subject to the same law as beasts - final destruction, the humiliation of extinction... Goodnight, dear heart, sweet - sister, mother. Think that we are together in the same bed. (BA307)

See Agnes Magruder and Arshile Gorky

September 30, 1941 - July 28, 1943: "New Acquisition: Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night" at The Museum of Modern Art.

End September 1941: Arshile Gorky and his new wife visit Chicago. (BA314)

They traveled by Greyhound bus to chicago and stayed with Gorky's sister Vartoosh and her husband (Mooradian). Four nights later they returned to New York. (BA314/316)

c. November 1941: Lee Krasner meets Jackson Pollock.

John Graham was planning a show at McMillen Inc. and wanted to include both Pollock and Krasner (as well as Willem de Kooning). McMillen Inc. was an antique and fine-furnishings company on East 55th Street. The idea was to pair established Europeans with new American artists. (JP106)

Although the show took place in early 1942 (JF53), according to Pollock biographer Deborah Solomon, "When Lee Krasner learned in November 1941 that John Graham planned to include her in the show 'American and French Paintings,' she was ecstatic that her work would be hanging in the same room as that of her idols Picasso and Matisse. But she was also curious: Who was Jackson Pollock and why didn't she know him?... She asked her friends in the American Abstract Artists group if they had ever heard of Jackson Pollock. No one had. Then one night she was attending an opening at the Downtown Gallery when she ran in to the painter Louis Bunce, a former schoolmate of Pollock's at the League. Pollock, he told Lee, was a very good painter who lived right around the corner from her, on Eighth Street. Lee was then living in a studio on East Ninth. The next day Lee walked over to his apartment. At the top of the stairs she was met by Sande Pollock, who pointed her to his brother's studio. Jackson must have been surprised by this woman in his doorway, who told him boldly, 'I'm Lee Krasner and we're in the same show.'" (JP107-8) Krasner later recalled her impression of Jackson's paintings in his studio - "To say that I flipped my lid would be an understatement. I was totally bowled over by what I saw." (JP108)

Lee Krasner:

I was terribly drawn to Jackson and I fell in love with him - physically, mentally - in every sense of the word. I had a conviction when I met Jackson that he had something important to say. When we began going together, my own work became irrelevant. He was the important thing. (JP109)

After visiting him in his studio, Krasner later remembered meeting him five years earlier at an Artists' Union party. Soon after meeting Pollock for the second time, they began to see each other on a regular basis. Previously she had been involved with a Russian émigré artist, Igor Pantuhoff, who studied under Hans Hoffman. Igor and Lee had lived together for two years sharing an apartment with Harold and May Rosenberg.

Lee Krasner:

Igor couldn't understand what Hofmann was doing... With their accents - Igor's Russian and Hofmann's German - they couldn't understand each other. So Igor just decided one morning that he was taking a bus across the country and going to become a great portrait painter. (JP114)

Pantuhoff left New York without telling Lee. She moved out of the room she had been sharing with him and set up her own studio on Ninth Street. (Igor would later become known as a "big eye" painter during the 1960s - painting kitsch portraits featuring large doll-like eyes.)

1941: "Directions of American Painting" at the Carnegie Institute.

302 paintings were included from nearly 5,000 submitted. American Scene painter Charles Burchfield was one of the jurors. Artists included Tosca Olinsky, Frank Kleinholz (Abstractionists), Dorothea Tanning and Jack Tworkov.

(SG220n56)

Late 1941: Arshile Gorky teaches camouflage.

On September 3, 1940 Gorky wrote to his sister Vartoosh that he planned to advertise that he was opening an art school. He had asked Edmund Greacen, the director of the reopened Grand Central School of Art, if he could use a classroom to teach camouflage. Greacen asked him to wait a few months to see if there would be sufficient enrolment as so many young men were being drafted. According to Gorky biographer Hayden Herrera, "The job teaching camouflage did not come through until the following autumn." (HH314) The following autumn would have been the autumn of 1941. However, Gorky biographer Nouritza Matossian indicates that Gorky "prepares camouflage course and publishes leaflet" in 1942 in her chronology of the artist's life. (BA549) Another Gorky biographer Matthew Spender notes that "the camouflage courses at the Grand Central School started late in 1941" (MS233) and that Gorky first asked Edmund Graecen about a job teaching camouflage in late 1939. (MS197)

Gorky enlisted the help of Frederick Kiesler (who would later design Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery) while researching camouflage and Kiesler filled several pages of drawings in one of Gorky's notebooks. (MS197) One idea Gorky had was to camouflage the entire city of New York in case of war. (BA321) The brochure for the class indicated a registration fee of five dollars and a course cost of fifteen dollars a month. (MS234) Gorky noted in the brochure, "An epidemic of destruction sweeps the world today... What the enemy would destroy, however, he must first see. To confuse and paralyse this vision is the role of camouflage." (BA321)

One of the students in the camouflage course was future gallerist Betty Parsons. She recalled attending a class of 20 - 30 people meeting twice a week for 3 to 6 months. (BA322)

October 1941: Arshile Gorky and Agnes visit Agnes' parents in Philadelphia. (BA318)

October - November 1941: Surrealist issue of View magazine.

Nicholas Calas was the guest editor. The largest section of the magazine was an interview of Andre Breton by Calas. Also included were drawings by Ernst, Sage, Matta, Dominguez, Lam and Tanguy and an article by Kurt Seligmann titled, "An Eye for a Tooth." (SS190-91)

October 2, 1941: J. Edgar Hoover writes to the NY office about the American Artists Congress.

According to Rothko biographer James E.B. Breslin, "On October 2, 1941 J. Edgar Hoover wrote to the FBI office in New York to complain that he had received 'no information' in response to his ordered investigation of the American Artists' Congress." (RO154)

November 12, 1941: The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors search for Patrons.

The Federation agreed to "concentrate on Patrons now - Businessmen later." (RO157) During a previous meeting they had compiled a list of 700 potential patrons to be part of a "Committee of Sponsors" and sent trial letters to 200 of them. Later they developed a plan for inviting businessmen (including Bernard Reis) to join the Ways and Means Committee as associate members (and $100 contributors). (RO157)

November 12 - December 30, 1941: "Annual Exhibition of Paintings by Artists under Forty" at the Whitney. (BA549)

Included Arshile Gorky's painting Garden in Sochi. (BA549)

November 14, 1941: The Atlantic Charter is announced.

The agreement between the Great Britain and the United States called for the defeat of Germany and promised self-determination for all countries, but it did not commit the Americans to military involvement in the war. No signed copies of the document are known to exist. According to one of the officials with Churchill's party, H.V. Morton, this was because Churchill and Roosevelt never actually signed it.

November 19, 1941 - January 11, 1942: Joan Miró and Salvador Dali exhibitions at The Museum of Modern Art.

The Museum of Modern Art lists both exhibitions as running concurrently. Arshile Gorky was known to have attended both. (BA318)

December 6, 1941: Great Britain declares war with Finland, Rumania and Hungary.

The government announced that from December 7th they would be at war with the three countries due to their refusal to cease hostilities against the Soviet Union.

December 7, 1941: The Japanese attack Pearl Harbor.

As a result of the attack, America finally ended its policy of isolationism and entered World War II.

Several weeks earlier, on November 17, 1941, the U.S. Ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, cabled the State Department warning them that Japan had plans to launch an attack on Pearl Harbor but his warning was ignored.

Barnett Newman:

I was sitting with [Adolph] Gottlieb in Union Square right after Pearl Harbor. I said that painting was finished. Adolph was more optimistic. It was he who first broached the idea that we needed a new subject matter... We respected the Surrealists but disagreed with their Marxist and Freudian approaches. Our orientation was more mythic. Gottlieb and I looked to primitive art. Our interest was in breaking out of art history as we knew it. (IS286)

December 8, 1941: Industrial camouflage exhibition at the Advertising Club opens.

Edward Alden Jewell reported in The New York Times, "The first exhibition that reported directly upon a phase of war technique itself was the admirably presented 'industrial camouflage' show at the Advertising Club. By coincidence, but none the less with startling effect, it opened twenty-four hours after Pearl Harbor." (SJ)

December 1941: Robert Motherwell returns to New York from Mexico.

New York would be Motherwell's primary residence for the next twenty-eight years. He abandoned his university studies permanently soon after his return in favour of becoming an artist. (RM131)

December 17, 1941: The Artists' Societies for National Defense meet.

Sometimes referred to as The Artists for National Defense, the group consisted of various artists' groups (including the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and the American Artists Congress) and urged "the creation of a government bureau whose sole purpose would be to commission art directed toward increasing civilian and military morale." (RO156) On January 19, 1942 they established the Artists' Council for Victory, an umbrella organization for twenty-three artists' societies.

December 31, 1941: The Hays buy a Rothko myth painting.

Mark Rothko and his wife spent New Years Eve with the writer H.R. Hays and his wife Juliette. As the Hays were about to leave their apartment Rothko called them and said that he and Edith were too broke to go. The Hays offered to pay and took them to the Stork club and the Hotel Pierre. Over dinner they said they wanted to buy a picture of his that they had seen at his studio and had "astonished" them because it was a "drastic change" from his earlier work. It was The Last Supper, one of Rothko's new works based on mythology. (RO159)

Two other works by Rothko based on mythology, Antigone and Oedipus, would be part of the Macy's exhibition/sale in January 1942. A Last Supper, The Eagle and the Hare, Iphigenia and the Sea and The Omen of the Eagle would be included in the "New York Artist-Painters" exhibition in 1943.

Adolph Gottlieb:

Rothko and I temporarily came to an agreement on the question of subject matter... Around 1942, we embarked on a series of paintings that attempted to use mythological subject matter, preferably from Greek mythology." (RO163)

According to Milton Avery's wife, Sally, their decision to paint myths was at a time when Gottlieb, Rothko and Barnett Newman were "obsessed with the idea of getting attention." (SW)

Sally Avery:

... it was really when they were so obsessed with the idea of getting attention and they decided to do these myth paintings, you know, Gottlieb and Rothko and Barney Newman. They were all going to do paintings based on myths. And that's the way they were going to attract attention. And they called Milton up and they wanted him to join them, but he said, "I'm not a joiner and I'm not interested in that.'" And Milton was really...he was really sort of...and he wasn't really interested in getting famous. I mean it was just a by-product of what he did rather than the main thing. He was really just interested in the next painting he was going to do... Well, Newman hadn't really started so much then. He was like a spokesman. He wrote about it. And it was only after he had written about it for a while that he decided he would get in the act too. (SW)