Abstract Expressionism 1956

by Gary Comenas

Mark Rothko moves his studio from West 53rd Street to 104 West 61st Street. "Modern Art in the United States" exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London. Joan Ward gives birth to Willem de Kooning's daughter, Johanna Lisbeth de Kooning. Time magazine refers to Jackson Pollock as "Jack the Dripper." Jackson Pollock meets Ruth Kligman at the Cedar Street Tavern. Ruth Kligman sleeps with Jackson Pollock in the barn with Lee Krasner in the house. Jackson Pollock and Edith Metzger die in a car accident. Ruth Kligman survives.

Franz Kline about Jackson Pollock: "The reason I miss him - the reason I'll miss him is he'll never come through that door again."

1956 - 1957: Barnett Newman doesn't paint.

Newman completed no paintings in 1956 and 1957 (or if he did, they were abandoned). (MH)

1956: Mark Rothko moves his studio.

Rothko moved his studio from West 53rd Street to 104 West 61st Street, now the home of Fordham University buildings. (RO628n33) His studio would remain at W. 61 St. until at least the spring of 1958 when the building was due to be demolished. In July 1958 he rented a large room to use as a studio in a former YMCA building on the Bowery (RO381)

Elaine de Kooning :

The place [on West 61st Street] was very tiny at that time and I remarked on it. I said, "Mark, I can't understand how you can work in such a small space." And he said, "I'm very nearsighted," which he was. He wore these extremely thick glasses. I said, "How lucky." He told me at that time - that was again in '56 - that he was lonely. He enjoyed my coming there and he enjoyed our discussions. He enjoyed talking about art from 10 o'clock in the morning until five o'clock in the afternoon, which is what we did. And he liked that one-to-one discussion. And he told me that an ideal life that he would conceive would be for - if he and Mel and Bill and I were off somewhere together in some isolated area but meeting every day and seeing each other every day. And toward the end of his life he did have that. He had these close friends that he would visit and so on. Of course, I think his attitudes were not really philosophically grounded. It was chemical. He was a sick man, as a result of that drinking, I think. And probably had had some strokes and so on. And [Theodoros] Stamos, who saw quite a lot of him at that time, felt that he was definitely not all there. (SE)

1956: Mark Rothko sells.

During 1956 Mark Rothko sold eight paintings for $6,805 (after a deduction of 1/3 gallery commission). (In 1955 he had sold six paintings for $5,471 after the gallery deduction.) (RO334)

January 5 - February 12, 1956: "Modern Art in the United States" exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London. (LM32) (Tate)

Exhibition catalogue for "Modern Art in the United States," Tate Gallery, 1956

The exhibition consisted of 209 paintings, sculptures and prints selected by The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

("Impermanent Invasion," Time, January 23, 1956)

Artists included Max Weber, Lyonel Feininger, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, George Bellows, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell and possibly Franz Kline. (Kline's obituary in The New York Times in 1962 mentions that Kline exhibited in a group show of American artists at the Tate in 1956 but doesn't specify the actual exhibition name or dates). (Rothko had refused to lend works to the London show so Dorothy Miller from MoMA borrowed Rothko paintings from collectors for the exhibition. (LM33))

Reaction by the British press was mostly negative. The London Sunday Times referred to the works in the exhibition as "Yankee Doodles" and John Berger wrote in the New Statesman, "These works in their creation and appeal are a full expression of the suicidal despair of those who are completely trapped within their own dead subjectivity." (LM33)

From Time magazine (January 23, 1956):

Londoners, who have long since succumbed to U.S. jazz, slang, movies and musical comedies, gave a less hospitable reception last week to modern U.S. art... As far as the Daily Telegraph was concerned, the abstract paintings of Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still and Robert Motherwell 'bombinate in a void. Nothing is communicated beyond an apparently fortuitous anarchy of pigmentation.' ... The arch-conservative London Times conceded that the abstract-expressionist movement is the 'one development in American art... [that] has gained for the United States an influence upon European art which it has never exerted before.' But as for the works themselves, the Times declared: 'The large, uncompromising canvases... have a monumental impermanence, show a defiance of Art and a kind of strange anonymity. They should be given the favorite American word of 'projects,' and seem intended for abandonment as the frontier advances, for are they not shock troops in the American invasion of painting?

January 29, 1956: Joan Ward gives birth to Willem de Kooning's daughter, Johanna Lisbeth de Kooning. (DK382)

According to Joan, the gossip amongst the art world, apparently spread by Elaine de Kooning, was that Joan had arrived at de Kooning's with "a pitcher of martinis" and that she had become pregnant in order to get Bill. The night she went into labour, she rang her twin sister Nancy and it was Nancy and Nancy's lover, Franz Kline who took her to the hospital. The baby was born an hour or two after midnight and de Kooning showed up in the morning. According to another couple who were there at the time de Kooning looked into the nursery window with his hands behind his back humming and repeating to himself "She's beautiful... she's beautiful." According to Joan, "Once she was born he fell in love forever." (DK383) Johanna lived with her mother but Bill tacked her photograph on his wall "among the reproductions of paintings, magazine ads, drawings and pinups." (DK383)

When Elaine went to the hospital to congratulate Joan, she found out that Joan had been admitted under the name "Mrs. de Kooning." (DK384) Elaine had just had a hysterectomy so knew that she would never be able to have a child herself. (DK385) According to Joan, when Elaine became aware that Joan had been admitted as Mrs de Kooning she joked, 'Oh... Bill and I always wanted to a child" and would tell others at the Cedar that the baby looked like Jackson Pollock. (DK385)

According to Alcopley, when he returned to New York in the spring of 1956 after having spent several years in Europe, Bill took him to see the baby - nicknamed Lisa - at Joan's apartment. When they passed the Cedar, Bill suggested going in for "one drink:"

Alcopley:

He had not one drink but several drinks. It seemed like he paid a few hundred dollars for everyone to have drinks. When we finally arrived at Leroy Street he was dead drunk and Joan was crying. She was afraid to let him hold the baby, but he insisted. So I put my arms under the baby as Bill held her so that she wouldn't fall. (DK384)

Lisa didn't realize that her parents weren't married to each other until she reached the age of twelve. (DK494)

February 14, 1956: Alfred Jensen visits Mark Rothko in his studio. (RO359)

Rothko discussed his own work with Jensen as well as the work of Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Picasso and Milton Avery.

see Alfred Jensen on Mark Rothko

February 15 - 16, 1956: Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt battle it out in court.

In an article entitled "The Artist in Search of an Academy" which appeared in the College Art Journal, Reinhardt characterized types of contemporary artists. One trend was the "cafe-and-club-primitive and neo-Zen-bohemian, the Vogue-magazine-cold-water-flat-fauve and harpers-Bazaar-bum, the Eighth-street-existentialist and Easthampton-aesthete, the Modern-Museum-pauper and international-set-sufferer, the abstract-'Hesspressionist' and Kootzenjammer-Kid-Jungian, the Romantic-ham-'action'-actor." (Reinhardt named Mark Rothko as one of these artists.)

Another type was "the artist-professor and traveling-design-salesman, the Art-Digest-philosopher-poet and Bauhaus-exerciser, the avant-garde-huckster-handicraftsman and educational-shop-keeper, the holy-roller-explainer-entertainer-in-residence." Reinhardt named Newman as such an artist and Newman sued him for libel. When the lawsuit reached the New York Supreme Court it was dismissed and an appeal rejected. (RO342-3)

February 20, 1956: Time magazine refers to Jackson Pollock as "Jack the Dripper."

Pollock was referred to by Time as "Jack the Dripper" in an article about the Abstract Expressionists who Time identified as Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell and William Baziotes.

From "Art: The Wild Ones" [Time magazine, February 20, 1956]:

Advance-guard painting in America is hell-bent for outer space. It has rocketed right out of the realms of common sense and common experience. That does not necessarily make it bad. But it does leave the vast bulk of onlookers earthbound, with mouths agape and eyes reflecting a mixture of puzzlement, vexation, contempt...

The young pioneers reproduced on the following pages took their lead from such European moderns as Kandinsky, Picasso and Paul Klee, and from a slightly less exalted group - Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipschitz, Piet Mondrian, André Masson - who sat out World War II in New York... The methods for doing this—abstraction and distortion—were as old as doddering modern art itself (i.e., almost a century), and had already been explored by older native sons from Arthur Dove to Stuart Davis...

The bright young proconsuls of the advance guard, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, added to this pattern of approach a breathtaking fervency and single-mindedness... The Pollock-De Kooning breakthrough soon found a following, and a label: abstract expressionism. Like most labels, this one has proved inadequate...

The advance guard is advancing in a number of different directions at once, and swiftly outrunning the abstract-expressionist formula. The variety of the paintings shown here—from De Kooning's gustiness to Guston's coolness—is in itself a strong indication of the movement's vitality...

Jackson Pollock's Scent is a heady specimen of what one worshiper calls his "personalized skywriting." More the product of brushwork than of Pollock's famed drip technique, it nevertheless aims to remind the observer of nothing except previous Pollocks, and quite succeeds in that modest design. All it says, in effect, is that Jack the Dripper, 44, still stands on his work...

The works featured in the article, in addition to Pollock's Scent, included Adolph Gottlieb's Blue at Noon, Robert Motherwell's Western Air, Willem de Kooning's Gothic News, Philip Guston's Summer (1954) and William Baziotes' Pompeii and Mark Rothko's Orange Over Yellow.

March 1956: Jackson Pollock meets Ruth Kligman at the Cedar Street Tavern. (JP246)

Kligman wrote about her affair with Jackson Pollock in Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock - a book that sometimes reads more like a Modern Romance comic (or an issue of the National Enquirer) than a serious account of the last days of one of the greatest artists America has produced.

According to Ruth Kligman she met Jackson Pollock the first time she visited the Cedar. She was working in a small gallery in New York at the time and her boss had given her the job of organizing a small show. One of the artists she planned to show rang to tell her that he had to drop out and to meet him at the Cedar so that he could explain.

Ruth Kligman [from Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock:

The taxi went east to University Place and Eighth Street... I lit a cigarette and arrived at a small, crummy-looking bar. There was a large circular sign in neon that said 'Cedar.' I walked in. It was very crowded at the entrance. A long bar extended for about twenty-five feet toward the back, where there were booths on both sides of the room. The walls were painted a pea-soup green. The place smelled faintly of stale urine, but it didn't matter. I was startled at all the activity this time of night. What a different world. A nighttime world I knew nothing about... (RK27)

After Kligman convinced the reluctant artist that he should show in her exhibition, Jackson Pollock entered the bar.

Ruth Kligman:

Suddenly the atmosphere changed. Jackson Pollock came storming into the bar. A general announcement was made. 'Pollock's here.' It was like hearing a trumpet calling everyone to attention; people transformed dramatically in seconds, expressions came alive... Then I laid eyes on Jackson Pollock for the first time. He looked tired out, sad, and his body seemed as though it couldn't stand up on its own. He was leaning against the bar as if for support... Our table was right smack in his line of vision. Strangely, Jackson was looking at me... Then suddenly I saw him on the way to our booth, with a drink in hand. Jackson joined the table. Jackson sat opposite to me. Yes. He had been looking at me. No. He was not interested in anyone else. I was introduced. "Jackson, this is Ruth Kligman. She's new on the scene, she's terrific, she's got a good eye, she's going to be somebody..." (RK29-30)

After their initial meeting, Ruth left the bar without Jackson and "waited patiently for Monday night."

Ruth Kligman:

The night we met was a Monday. I had been told Monday was his day in town, his day to see his analyst, and that he always stopped at the Cedar before driving to his home in Springs. My plans were made. Instead of going there alone, I would call the bar and leave it in the hands of fate... I would try every Monday until I reached him. (RK40)

Ruth rang the bar on a Monday and managed to get through to Jackson. He asked if he could come over and she gave him her address. He arrived and she opened a bottle of wine, telling him about the first time she had seen one of his paintings. According to Kligman, she said "I remember the first painting I saw of yours about two years ago. It was all black and white, and I remember standing in front of it, and something happened to me. I felt the sensation of you, your energy came into my body...I was so moved by your work, your beauty, the mobility, the lyric quality, the torrent, the suffering, it's all there... I felt your tears, I felt your heart breaking, I felt betrayal, and your violence and rage, and my heart was breaking with you." (RK42-3)

And then, again according to Ruth, Jackson started crying until "passion took over."

Ruth Kligman:

His crying went on for a long time... He seemed to be crying for his entire life.. He was crying out to be held, pacified, needed, loved, forgiven, adored, and I said, Yes, I will give you anything you want. I moved toward Jackson. I took his head in my arms and held him close to my chest... He couldn't believe I wanted him and moaned little endearments to me. His smile lightened his face, and then his passion took over. The crying was a disease that allowed him to be his own man. He took me powerfully, with great confidence.... Finally a man who wouldn't take me as a casual affair... (RK44-5)

Jackson and Ruth continued to see each other with Jackson meeting up with her on several occasions after seeing his analyst in Manhattan and speaking to her on the telephone when he wasn't in town. According to Ruth, "he called me every other day, long conversations, sometimes two hours at a time." (RK60)

March 5 - 31, 1956: Franz Kline solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery.

It was Kline's first exhibition at his new dealer's gallery. (FK179)

April 3, 1956: Willem de Kooning's second one-man show opens at the Sidney Janis Gallery on Easter Monday.

Janis was relieved to see that de Kooning had returned to abstraction. (DK387) De Kooning often took a considerable amount of time getting his paintings right and had apparently finished one the works shown at the exhibition on the day of the opening of the show and named it "Easter Monday." (DK380)

According to poet and writer Selden Rodman who was at the opening, the show was a "complete sell-out." Both Jackson Pollock and Franz Klein attended the opening party - and the Cedar Street Tavern afterwards.

Selden Rodman:

I ran into Jackson Pollock less than a week after returning to New York from Taliesin West. There had been a party for Willem de Kooning, following the opening of his show at the Sidney Janis Gallery. The party was in a dive on 10th Street. By the time I arrived de Kooning had moved on, but among the stragglers I found Larry Rivers, Franz Kline and Pollock. Kline said: "Everybody's gone to the Cedar Bar. Let's go." But Pollock wasn't going anyplace. At least not yet. He was dancing. He had a battered brown fedora clamped over one eye, and his face was swollen and badly scratched.

I hadn't seen Pollock since a visit to his home in Springs, Long Island, about four years back, save for a brief encounter at the opening of Matta's show two years ago. On that occasion I had heard him mutter "Technicolor..." in his beard as he went out the door...

With David Smith I walked over to the Cedar Bar. De Kooning was there and ordered drinks for us. He insisted on paying for them, but Smith wouldn't let him. "Wait till you sell a painting, Bill." Smith hadn't been to the opening or heard that de Kooning's show was a complete sell-out. He himself had had a show of his sculpture recently at the Willard Gallery, the net result of which had been one piece stolen... (CW76-78)

May 1956: Donald Blinken buys Mark Rothko's Three Reds (1955). (RO639n22)

May 1956: Jackson Pollock is chosen by The Museum of Modern Art to open a series of exhibitions on artists in mid-career.

Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, Director of the Painting and Sculpture Department at The Museum of Modern Art, originally wanted Willem de Kooning to be the artist who inaugurated the "Works in Progress" series but was overruled by Alfred Barr who thought Pollock was "more deserving." (JP244) The Pollock exhibition was to include up to twenty-five pictures. (PP328)

May 30-September 8, 1956: "Twelve Americans" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition consisted of work by eight painters and 4 sculptors. The painters were: Ernest Briggs, James Brooks, Sam Francis, Fritz Glarner, Philip Guston, Grace Hartigan, Franz Kline and Larry Rivers. The sculptors were: Raoul Hague, Ibram Lassaw, Seymour Lipton and José de Rivera. (S.P., "About Art and Artists: Work of 12 Contemporary U.S. Painters and Sculptors at the Modern Museum," The New York Times (May 30, 1956))

Stuart Preston reviewed the show for The New York Times (June 3, 1956):

Franz Kline's painterly acrobatics never lack for confidence but strike me as rhetorical when compared with Fritz Glarner's thoughtful, delicately wilful overlapping of color... Few can fail to be intrigued by the relentless with which Philip Guston builds up his crescendos of color, from dawn's early lights to a pigeon-blood of climax.

c. June 1956: Jackson Pollock rejects label of "Abstract Expressionism."

Jackson Pollock commented that he didn't care for the label of "Abstract Expressionism" (or "nonobjective" or nonrepresentational") in an interview with Selden Rodman for the book Conversations with Artists. In his book Rodman notes that the interview took place in the Springs "eight weeks before Pollock's tragic death in August 1956." (CW76) During the visit Rodman and Pollock went to see Pollock's neighbour, the artist Conrad ("Corrado") Marca-Relli.

Selden Rodman:

Having noticed Julian Levi's [sic] mailbox on one side of his [Jackson's] house and Corrado Marca-Relli's on the other, I asked him [Jackson] whether he saw much of these artists... Marca-Relli was a close friend, Pollock said. "Shall we walk over and see him?" We walked along the highway, a somewhat hazardous route, since he became involved in trying to tell me why none of the conventional labels fitted his own painting, and as he did so wandered off toward the center of the road - down which Sunday drivers were hitting 60 - gesticulating and paying no attention to them at all except now and then to grab me by the elbow and say, "Look out! This road is dangerous!"

Marca-Relli, who was building an addition to his house, came to the door, and provided us immediately with cans of beer. His beard is black, and perhaps because it is more luxuriant and curly than Pollock's brown one, gives him a more benevolent appearance. I told them that they reminded me of the Smith Brothers and that I'd like to photograph them together on the sofa, which was just big enough for two. I asked Pollock, meanwhile, to elaborate on this business of labels.

"I don't care for 'Abstract Expressionism," he said, "and it's certainly not 'nonobjective," and not "nonrepresentational' either. I've very representational some of the time, and a little all of the time. But when you're painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge. We're all of us influenced by Freud, I guess. I've been a Jungian for a long time."

"When you start a picture," I asked him, "do you have any preconceived visual image in mind, or is the result wholly spontaneous, something that happens in the process of painting?"

When Pollock prepares to answer, he squints, screws up his face, tilts it to one side. "How do I know? I have and I haven't. Something in me knows where I'm going, and - well, painting is a state of being." (CW81-2)

Later in the interview Pollock comments that "The important thing is that Cliff [Clyfford] Still... and Rothko, and I - we've changed the nature of painting." (CW84) When Rodman asks him why he left out de Kooning, Pollock responds, "I don't mean there aren't any other good painters. Bill is a good painter but he's a French painter. I told him so, the last time I saw him, after his last show... You know what French painting is. If you don't, you won't see what I mean. All those pictures in his last show start with an image. You can see it even though he's covered it up, or tried to... Style - that's the French part of it. He has to cover it up with style." (CW85)

Jackson offered to show Selden some of his current work in his studio in order to better explain what he was talking about and Rodman and his wife Maia followed him to the outbuilding he was using as a studio but Jackson was unable to find the key. He then went into the house to ask Lee Krasner if she had a key and returned without one.

Selden Rodman:

In about five minutes he [Pollock] returned shaking his head. "Lee hasn't got one either. There just isn't any key," he smiled wryly. "There's something for the analyst!" he said. "The painter locks himself out of his own studio. And then has to break in like a thief."

Before we could stop him he had smashed a pane of glass.

"Couldn't we force the window?" I said.

He tried, but without success. There were wedges nailed in from the inside.

"Damn!" With his elbow he smashed another pane, and then another, tearing away the wooden strips between them. "Wait, I'll get a hammer and really go to work on this." He ran back to the house while we collected the splintered glass in a pile. Returning with the hammer, he finally managed to raise the lower half of the window and, showing a table covered with dusty sketches out of the way, stepped in. We followed him. The main studio was an extraordinary sight. Huge paintings some of them twenty or more feet long, demonstrated clearly enough what he had meant. They were not French, or even American. They were simply Pollock... Even the patterns of paint on the floor itself, where lines and drops of pigment had spilled over from the edges of the recumbent canvases, were recognizably "Pollock." (CW85-6)

Rodman's wife Maia later recalled that during the time they were in Pollock's studio Rodman went back into the Pollock's home, leaving Maia and Jackson alone in the studio. Pollock began to sob uncontrollably. Pointing to paintings leaning against the studio wall, he said to her "Do you think I would have painted this crap if I knew how to draw a hand?" (JP240)

c. Early June 1956: Ruth Kligman and Jackson Pollock break up.

According to Ruth Kligman, "Jackson came to the city unexpectedly. His doctor had gone to the Cape for the summer, and somehow Jackson tracked me down to my friend's apartment on Fifty-fifth Street, where I was staying... He walked in unannounced, and my friend said later that Jackson had looked like Death. I couldn't go with him. It was over. We went to a bar to be alone and I tried to explain my feelings." (RK72-3)

At the bar Ruth told Jackson that her analyst had advised that she end their relationship. According to Ruth, Jackson then told her that his analyst had told him the opposite - that the relationship was a good idea. When she insisted that they stop seeing each other, Jackson replied (according to Kligman) "I understand; I don't agree but I understand... We'll meet again... if not in this life, then in another." (RK73)

Although in Ruth's account she maintains that she was the one who wanted to end the relationship, she also recounts how devastated she was by the break-up. Fortunately her flatmate was on hand to put her to bed "with a stiff drink and love."

Ruth Kligman:

I got up and ran out of the bar... I ran wildly down Eighth Avenue, holding edges of buildings, the black of my mascara blinding me... I never wanted to leave him, that face of my interior soul sitting at the bar alone. His heart spilling over the table like Dali's watches... I threw myself on the floor of the apartment. The coolness of the cheap linoleum warmed me... My friend found me lying on the kitchen floor, weeping and half asleep from exhaustion. She picked me up, washed my face, and put me to bed with a stiff drink and love. Yes, I needed sympathy for a change. I was not strong and the bones were broken in my aching heart... (RK74)

June 1956: Jackson Pollock at the Cedar.

Fielding Dawson, an ex-student of Franz Kline and a Cedar Street Tavern regular, described a night at the Cedar in June when Jackson was allowed to return after having previously been kicked out ("86'd"). Previously, Kline had pointed to the door of the men's room (which Dawson notes wasn't "very straight on its hinges") at the Cedar and told Dawson that Jackson had, one night, "ripped it off its hinges."

Fielding Dawson [from An Emotional Memoir of Franz Kline]:

... I was sitting at the bar having a beer, and I heard John, the bartender, murmur, "Oh. No." In the small square window of the red front door, I saw a part of Jackson's face; one brightly anxious eye was peering in. John walked down the duckboards towards the end of the bar near the door, and stopped, put his left fist on his hip, and extended his right index finger at the small window. He shook his head. The eye looked hurt. John was tightlipped. I was laughing. The eye disappeared. John muttered out of the corner of his mouth and he is a man who can mutter out of the corner of his mouth, "He'll be back."

We watched the square window. Jackson's eye peeped in. "No!" John yelled. "You're 86 Jackson!" The eye was sad and puzzled. Me 86? The eye got angry. Jackson's face slid across the window; then his whole face was framed by it; mask of an angry smile. "No!" John shouted, shaking his head. "Beat it!" Jackson's eyes became bright and he smiled affectionately. John shook his head. "Whaddya gonna do? I can't say no to the son of the bitch." He sighed. "All right!" he cried and pointed to the window, wagging his finger, "But you've got to be good!... Remember - one trick and you're finished... No cussin', no messin' with the girls." Jackson said, darkly, "Scotch." With the drink in his hand Jackson... made his way toward me... "Okay if I sit here?" I stammered sure Jackson sure, and in my apprehension rather compulsively arranged the pack of matches exactly in the center on top of a new pack of cigarettes. Jackson watched me... He gravely shook his head. Wrong. He crushed my smokes and matches in his left hand.

He gazed back where people sat at tables, eating supper... They had come from the Bronx, from Queens, from New Jersey and from the upper East Side to eat at the Cedar and wait until Jackson finished his fifty minutes with his analyst, and came down to the bar to play... Pity the poor fellow that brought his date in for supper, for Jackson was happy to see her. He immediately sat beside the fellow, glared nastily at him and then gave his full crude nonsensical attention to the girl while the fellow said - something - timidly - "Say, now just a minute -" Jackson turned to him, and looking at the poor guy with a naughty smile, swept the cream pitcher, salt, pepper, parmesan cheese, silverware, bread, butter napkins, placemats, and drinks on the floor..." (FD78-81)

Sunday, June 1956: Ruth Kligman moves to Sag Harbor.

Ruth found a summer job through The New York Times to be a monitor at the "Abraham Rattner School of Art" in Sag Harbor in East Hampton (where Jackson was living in the Springs) in exchange for free accommodation (in Mrs. Boyd's house, 106 Main Street) and painting lessons from Mr. Rattner. (RK72/77) According to Ruth, Jackson managed to track her down and rang her.

Ruth Kligman:

... I thought I had solved everything by taking this job, far away from New York where Jackson couldn't find me. I had told him about the school and the job, and when we broke it off that last time he hadn't said anything about the proximity between Sag Harbor and Springs. And I didn't know. Or did I? (RK79)

Jackson and Ruth began seeing each other again and, according to Kligman, Pollock asked her to marry him during dinner at a seafood restaurant.

Ruth Kligman:

We were both born under the same sign of Aquarius. We both felt it was a predestined fact that we would be together... when Jackson asked me to marry him I was at first startled by the idea, but I realized our relationship was that important... I knew the divorce would take time, and then felt more secure in Jackson's love for me... We ate a huge dinner, went back to my house, and made love. Somehow it didn't work that night. Jackson blamed the drinking. He started crying. "I must stop drinking the goddamn stuff, especially to keep a young wife happy." (RK88)

Summer 1956: Mark Rothko is bedridden for two months. (RO362)

Rothko had originally been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis but as his condition worsened, Herbert Ferber suggested that he consult another doctor - Albert Grokest. But when Grokest visited the artist in his 54th Street apartment, Rothko told him he didn't trust doctors and refused to give him a medical history. As they talked the doctor noticed a "lumpy whiteish mass" in Rothko's ears and diagnosed gout (which can be made worse by being bedridden) rather than arthritis. Rothko was given a prescription for colchine and his condition improved. (RO363)

Albert Grokest:

I don't think he [Rothko] trusted anybody. And it went back to his mother and father starting with them. He had zero trust in his parents, and that led to this extended protracted distrust in the outside world. (RO363)

According to Grokest, Rothko had "been drinking and living high and getting overweight." He thought the artist found food and alcohol "far more consoling than people." (RO363) Grokest, who shared Rothko's interest in music, would remain his physician until the artist's death. Rothko saw him in his office for the first time in November 1956 and then again in February 1957, October 1957, May 1958, November 1958, December 1958, May 1959 and June 1959. Grokest recalled "He would wait until everything was caving in, then we would call on me." (RO364)

Elaine de Kooning:

He [Rothko] was a secret drinker. You know, at parties you didn't feel that Rothko was drinking more than anyone else. He never got drunk, and his secret drinking also did not make him drunk. But he would start at 10 o'clock in the morning. I discovered this when I went to write the article about him, I think in 1956. He offered me a drink at 10 o'clock in the morning and I said, "No, I haven't had breakfast yet." And Rothko said that he took one drink an hour all day long. Of course, that's really deadly drinking, because it makes liquor part of the bloodstream. But he never, ever got high. You never saw Rothko so that you felt he'd had a drink. It was always completely contained. (SE)

Rothko's wife, Mell, was also a drinker. She visited Dr. Grokest in 1957 complaining of numb fingers and told him that she was drinking "heavily." During the next two years she had two serious falls which Grokest thought had to do with her drinking. According to Grokest she stopped seeing him because "she didn't like my emphasis on her substance dependence." (RO369)

Summer 1956: Franz Kline stays in Provincetown with Al Leslie. (FK179)

June - October 1956: Franz Kline's work is shown at the 28th Venice Biennale.

c. July 5, 1956: Ruth Kligman sleeps with Jackson Pollock in the barn with Lee Krasner in the house.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, 1956

(Photographer unknown)

Lee Krasner discovered Ruth and Jackson as they were walking toward the car after they had secretly spent the night together in the barn while Krasner was sleeping in the house. According to Kligman they had been involved in a car accident earlier in the evening on the same night. Jackson had lost control of the car as it "swerved around in a perfect circle, like a swivel." Kligman later claimed that she had a premonition after the accident that her and Jackson would "die together in a car accident." (RK94)

Lee caught them the next morning after they left the barn. Kligman reacted with childish glee.

Ruth Kligman:

Halfway toward the car we saw Lee on the back porch... Her face distorted with anger, her body shaking. She stared at me, trying to utter something coherent, stuttering and finally screaming at us, calling out, "Get that woman off my property before I call the police!" ...We ran to the car laughing like two children being scolded by the big bad mother. It was the funniest scene, at her expense; all the way to Sag Harbor we were laughing hysterically. (RK95)

July 9, 1956: Jackson Pollock asks Ruth Kligman to move in after Lee Krasner decides to leave for Europe.

Ruth Kligman:

I didn't hear from him [Pollock] for three days. Then the call came. "Lee's leaving, she's going to Europe.. When I returned to the house that morning, she was in a hysterical condition, out of control. I tried to talk to her, tell her it was over, but she didn't believe me... She said 'Either you stop seeing Ruth or I'm leaving,' so I said go... She's leaving the day after tomorrow... I'll call you tomorrow. Be ready with your things the day after. I'll let you know where I'll pick you up..." (RK96)

July 12, 1956: Lee Krasner goes to Europe.

Ruth Kligman moved in with Jackson in the Springs for a brief time during Krasner's absence. (PP328) Although Pollock talked about getting back to work, he never did. In the meantime Lee was sending postcards and letters from her European trip - "It would be wonderful to get a note from you" she wrote to Pollock, also telling him that she visited a flea market with John Graham, Van Gogh's "last painting place" in the south of France and planned to continue to visit Venice to stay with Peggy Guggenheim but Guggenheim refused to see her. By the end of July she was back in Paris staying with the painter Paul Jenkins and his wife on the Rue Decrès. (JP247)

July 1956: Jackson Pollock and Ruth Kligman attend Clement Greenberg's dinner party.

Greenberg was renting a house for the summer in East Hampton.

Ruth Kligman:

I was so excited about meeting Clem. he was a very famous and influential art critic and writer who was close to Jackson for years. I also knew that Clem was a good friend of Lee's. I was nervous about what to wear, and what to say, yet really looking forward to the evening. I wanted Clem to like me... The house was near the town, and we arrived late... I was introduced all around, and their casual attitude toward my presence must have been studied. They were all dressed in blue jeans and with no style. I felt overdressed... It was again as though I were invisible, as though I were talking to myself. I was totally ignored. Jackson did nothing to help me out. He didn't even include me in the conversation. I felt like a piece of furniture. Toward the end of this nightmare, Clem became personal with Jackson and asked him his plans about me and what his intentions were toward his wife. He was really quite abrupt with Jackson. I waited for Jackson to retaliate, waited and waited, but he just sat there taking the blows... Then Clem became brutal. I don't know exactly what the words were, but it was an insult. He was strong and rash. Jackson got up quietly and without a word walked toward the door. "Come on, Ruth, we're leaving." (RK122-3)

Early August, 1956: Jackson Pollock tells Ruth Kligman that Lee Krasner is coming back.

Ruth Kligman:

He [Jackson Pollock] had the morning mail. I immediately spotted the pale blue airmail stationery. He held the letter in his hand and sat there reading it over and over.

"Good morning, darling. What can I get you? What is that letter?"

"It's from Lee. She's been in Venice and Paris and is coming back soon."

"When?"

"After Labor Day, or whenever I say. She's waiting for the word from me." (RK150)

Tuesday, August 7, 1956: Ruth Kligman tells Jackson Pollock she is going to New York for a few days.

Kligman had decided to go to New York after attending another party with Pollock in East Hampton where, once again, she was ignored.

Ruth Kligman:

We arrived at a rather large, imposing East Hampton house with lots of cars parked all over... He walked in to what seemed like thunderous applause - everyone stood up and cheered... He was surrounded, instantly surrounded. Jackson, Jackson. I was ignored... Women gleefully sat at his feet, on the arm of his chair; rich people patted him on the back, he was soaring... I became black. I was stuck with his despair. I drank... He was the Star, he knew how to move, to get what he wanted. Everyone else was his supporting player. I was so jealous. I wanted that power to command, to control, to lead. I watched him through my glazed eyes. (RK167)

She made the decision she needed a short break from Jackson by the Tuesday after the party. According to Ruth, Pollock initially didn't want her to go but she convinced him it would be a good idea.

Ruth Kligman:

I needed his approval and could not go if he did not approve. My plans were made. I would leave on a Thursday and say I had to see my analyst on Friday and return on Saturday. That would give me two entire days alone in New York... I called a friend when Jackson was in town and asked her if she could put me up a couple of nights. Her answer was yes, and the most important problem was solved. When Jackson came back I told him my plans. "I must be in New York on Friday because my analyst has just arrived from Europe and I would like to see him. I just spoke to him on the phone, and he will see me this coming Friday." I talked fast and casual at the same time. (RK171)

Jackson was suspicious. Why had Ruth made her plans secretly? He suggested that he drive her to Manhattan on Friday, then wait for her to see her analyst and drive her back to the Springs the same day. She said, no, she wanted to visit her family. She would take the train. (RK171-2)

Thursday, August 9, 1956: Ruth Kligman arrives in New York.

Jackson took Lee to the train station and saw her off, waiting in his car until the train pulled out. She arrived in Manhattan later that day.

Ruth Kligman:

I walked toward Fifth Avenue and up. The afternoon was brilliant, everything glowed from the sun. There was a motion to the crowds and an energy that exhilarated me. I felt very calm and in tune with myself. I loved Fifth Avenue, my shops, my favorite hotel in the world, the Plaza. I loved the limousines and the well-dressed women near Bergdorf's, the good-looking me that glanced at me and were going somewhere. I often wondered what kind of lovers these men were, the ones that wear suits and ties in the summertime and have expensive lunches. Were they good lovers underneath their well-cut suits? (RK176)

Friday Afternoon August 10, 1956: Ruth Kligman has lunch with Edith Metzger.

Twenty-five year old Edith Metzger worked as the receptionist at the beauty parlor that Ruth went to regularly in New York. They had become friends.

Ruth Kligman:

... since I was eighteen or so, I had liked the ritual of beauty parlors... I loved getting set and sitting under the dryer reading Vogue or movie magazines and putting mascara on while still under the dryer, because somehow the heat from the dryer made the mascara work better and my eyelashes would be thicker and longer... I became friendly with the receptionist at the beauty parlor. I didn't know but later found out she was the mistress of Nicky, the owner, whom she adored. Her name was Edith. She was about twenty-one or twenty-two, and we got to be friends. She lived somewhere in the Bronx with her mother and her youngest brother. She was rather secretive about herself. All I knew was that she had been born in Germany, and because they were a Jewish intellectual family, they had to leave because of the war... Neither of us had a father. Her father was killed during the war, and I had never lived with mine... She talked about her affair with her boss, which was the reason she kept that job... He was married with two little girls and a very nice, attractive wife... I approved of their relationship [Edith and Nicky]. I encouraged it, and gave her courage to go on when she weakened... (RK65-6)

Over lunch Ruth admitted to Edith that she had lied to Jackson about her reasons for coming to New York and asked Edith to come with her when she returned to the Springs the next day to spend the weekend with her and Jackson. Although initially reluctant, Edith finally agreed to go saying she was "so anxious" to meet Jackson. (RK181)

Friday Evening August 10, 1956: Ruth Kligman has a date with a Jewish comedian.

The night before she returned to the Springs, Ruth had a date with a Jewish comedian who she already knew. According to Kligman, she arranged the date "on the spur of the moment" after arriving back in New York.

Ruth Kligman:

Cheating on Jackson! Away from him for two days and already I had another date... He was a stand-up comedian telling me all the jokes, at the same time he told me how pretty my eyes were... I felt good being with him, it was different from being with Jackson. I felt my own age. This seemed more contemporary, more real. Yet the other was my reality. I needed Jackson's strangeness, that conflict... Jackson was the ultimate mystery, my deep love, my archetypal lover and father. We were historic together. We were the great romantic couple of our time. (RK182-3)

August 11, 1956 (Morning): Ruth Kligman returns to the Springs.

Ruth returned to the Springs, accompanied by Edith Metzger, on the 7:05 train from New York. They were met at the East Hampton train station by Pollock. On the way back to the house, Jackson stopped at Cavagnaro's where the two women drank coffee and Pollock drank beer. He continued to drink through the afternoon. At one point Ruth took Edith to see Jackson's studio.

Ruth Kligman:

Jackson had not been working. He went to the studio only if some visitor was important enough. Then he would show his work. I walked in front of Edith. The sun was coming through the large overhead skylight. I was taken aback, as I had been the first time I walked in... We were overwhelmed. His largest canvases covered the walls, every inch of space was covered by his work... Tears came to Edith's eyes, soft small drops on her cheeks. She started to talk.

It was as though Edith went into a trance. Suddenly out came the story of her very early life in Germany. Stories I had never heard of her background...'My father's best friend was killed by the Nazis, and many of my family. We were lucky we escaped to America, but my father couldn't take it. Somehow he couldn't take the life here. Germany and the Nazis had shattered his will, had left him a broken man, a man without resources. "Ruth, I loved him so much and was never happy, he never made it." She was crying; I went to her and put my arms around her. I told her to cry and let it out. (RK194-5)

August 11, 1956 (Night): Jackson Pollock and Edith Metzger die in a car accident. Ruth Kligman survives.

By the evening, and numerous drinks later, Jackson was feeling better. After making Ruth and Edith a steak dinner he told Lee that they had been invited to Alfonso Ossorio's house. Ossorio had just returned from Europe and was having "some kind of musicale" at his home. (RK197) Edith was reluctant because of the cold shoulder she had experienced from guests at previous parties they had attended in the Hamptons, but eventually it was agreed that they should go. On his way to the car Jackson staggered and Edith asked Ruth if he was "all right? I mean, are you sure he can drive? He's been drinking all day." After reassuring words from Ruth they got in the car - all three in the front seat. (RK199)

Ruth Kligman:

We drove toward East Hampton. Jackson drove fine, then suddenly started driving very slowly, then slower and slower. Finally he came to a full stop in the fork of the road.

"What's the matter, Jackson? Are you all right?"

"I'm fine. I just want to stop for a moment."

Just then a police car pulled up. An officer walked over. He recognized Jackson and the car. They knew each other.

"Good evening, Mr. Pollock. Is there anything the matter?"

"Hello there," Jackson alerted, "nothing's wrong, we were just talking. How are you?"

"I'm fine. How are you? Do you need any help?"

"No, thank you. We're visiting friends in East Hampton."

Edith and I were as still as mice, not knowing what to do or say. I realized he was drunk.

Edith whispered to me, "Ruth, he's drunk. Let's go home."

"Take it easy. He knows what he's doing. Don't worry."

... After the cop left we started again on our way to East Hampton. Again he couldn't make it. Again he started to fall asleep. He drove about twenty miles per hour, his great head falling, his eyes glassy, moaning incoherently. I wished to God I knew how to drive.

"Jackson, please let's go home"... We got him to stop. He turned around in front of the Cottage Inn, a roadhouse bar, a dancing place frequented by Negroes. It was Saturday night; there were a lot of cars around.

Edith quickly got out of the car. "I'm going to call for help or call a cab; I must do something." She was panicked. She was right, but I called her back.

Jackson got furious. "She can't go in there, get her back." Then he mumbled drunkenly, something about involvement with Negroes, some disapproving puritanical remark.

"Edith, get back in the car. Come on! Don't go in there!"

"But Ruth, he's drunk. I don't want to drive with him. I'm afraid."

"No, he's not, he's fine, I promise you, we're going home. Come on! Get In!"

... I finally coaxed Edith to get back in. We started on our way home. Jackson was fully awake, fully conscious. He was angry, annoyed at us, and began to speed.

Edith started screaming, "Stop the car, let me out!" She was pleading with him. Again she screamed, "Let me out, please stop the car! Ruth, do something. I'm scared!"

He put his foot all the way to the floor. He was speeding wildly.

"Jackson, slow down! Edith, stop making a fuss. He's fine. Take it easy. Please. Jackson, stop! Jackson don't do this." I couldn't reach either of them.

Her arms were waving. She was trying to get out of the car.

He started to laugh hysterically.

One curve too fast. The second curve came too quickly. Her screaming. His insane laughter. His eyes lost.

We swerved, skidded to the left out of control - the car lunged into the trees.

We crashed. (RK199-201)

The car had crashed into two small elm trees. All three were thrown from the car. Jackson and Edith were both dead. Ruth survived.

Clement Greenberg tried to locate Lee Krasner in Venice to tell her the news but was unable to find her. He rang Paul Jenkins in Paris to ask if he knew where Lee was. Paul told him she was there with him, standing right next to him. As Greenberg told Paul what had happened Lee overheard the bad news. "Jackson is dead" she screamed, crying uncontrollably. (JP248-9) She returned to New York immediately. (PP328)

Jackson's death made the front page of The New York Times and was covered in most of the major newspapers and magazines. Time magazine referred to him as the "shock trooper of modern painting." Life magazine captioned its obituary "Rebel Artist's Tragic Ending." (JP250)

August 12, 1956 : Willem de Kooning learns of Jackson Pollock's death. (JP/PP/DK393)

De Kooning was staying with Joan Ward on Martha's Vineyard at the time. The artist Herman Cherry, who was staying in a rented home down the road and knew de Kooning from the Cedar, broke the news.

Joan Ward:

Bill was painting on the porch and I was inside. Herman, with his face down to his knees, says, "Bill here?" I said, "Yeah, he's out on the porch." He went out with heavy shoulders sagging. I heard voices going on. About ten minutes later they come in, Bill looking rather startled, rather like the White Rabbit, you know, "What am I supposed to be doing here." Then he said, "I guess we better tell Joanie. Jackson Pollock was killed last night in an automobile accident." (DK393)

Pollock's old mentor, Thomas Hart Benton, learned the news of Pollock's death from Cherry and de Kooning. The Bentons were sitting on their porch in Chilmark when the two arrived. Thomas and his wife were devastated by the news. De Kooning and Cherry offered to fly them to the funeral but Benton replied that he "couldn't take it." His wife Rita showed Cherry and de Kooning a stack of clippings about Pollock that she had saved over the years and kept in a drawer. (JP251)

Cherry charted a plane to attend the funeral and de Kooning went with him. Elaine had returned from Europe on August 13th (JP250) and joined them for the flight back to Martha's Vineyard. Her arrival came as a shock to Joan who had not heard from Bill and was not aware when he would be arriving back or that he was bringing Elaine with him.

Elaine and Bill stayed at a house rented by the sculptor David Slivka. After two days, a friend of Joan's who was staying with her decided they would give a party to "put on a good face." (DK395) Although Elaine attended the party, Bill did not. When Joan saw her, she asked a friend to tell her to leave. The following day Joan's friend saw Cherry and de Kooning at a gas station and de Kooning got out of Cherry's car and into the friend's car and they returned to Joan's house where Joan and Bill started quarreling. The next day Elaine visited the house, accusing Joan of wearing a fake wedding ring. Joan responded, "It's no phonier than yours." Elaine called her "a little girl from Scranton." Joan replied that she wasn't from Scranton "for god's sake" and said "Somebody from Brooklyn isn't going to tell me what to do" and picked up Lisa (her daughter by de Kooning) and shut herself in the bedroom. Elaine went to the airport and took a plane to Provincetown. (DK396)

In Manhattan, the Cedar Street Tavern regulars drank to Pollock the night after his death and shared stories about his life.

Fielding Dawson:

The evening following the morning Jackson was killed I went in the Cedar and Franz [Kline] was at the end of the bar, crying, slumped on a barstool. He'd stayed up with a bunch of painters telling stories, laughing and drinking to Jackson, and somebody said "Jackson would have liked it," which might have been true, but there was no doubt, when Franz was talking, Franz would be the man to listen to, and surely Franz joined in to soothe the shock.

By nightfall he was exhausted. I stood beside him drinking a beer, and he looked up, saw me looking at him tenderly. He touched me, and later, I asked him, perfectly, what he thought Jackson had done.

Franz responded softly as tears ran down his cheeks.

"He painted the whole sky; he rearranged the stars, and even the birds are appointed."

He looked up in misery and pointed down at the front door of the bar, and said huskily,

"The reason I miss him - the reason I'll miss him is he'll never come through that door again."

Then he really let it come." (FD87-8)

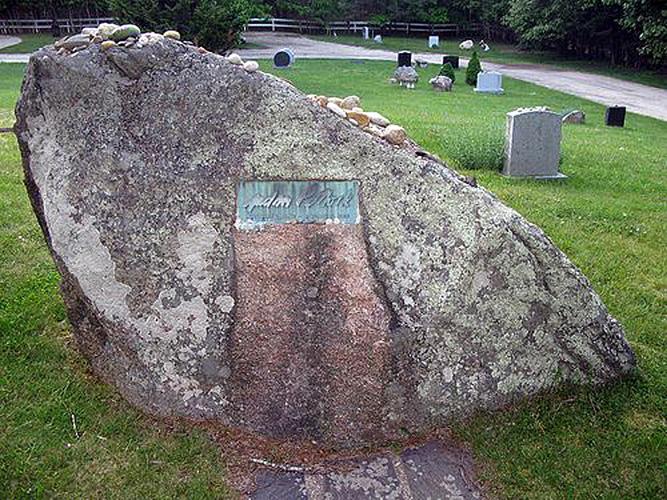

August 15, 1956: Jackson Pollock's funeral is held.

Jackson Pollock was buried in Green River Cemetery in the Springs. Later a boulder would be erected on the grave to mark it. (JP251)

The funeral was held at the nondenominational Springs Chapel located near to Pollock's house. About 200 people attended. One of the guests at the funeral was Jackson Pollock's mother. At the age of 81 and suffering from phlebitis, she had managed to survive her son. (JP251) Lee Krasner asked Clement Greenberg to deliver the eulogy but he declined - he didn't want to praise "this guy who got this girl killed." No friends spoke at the funeral. A brief service was conducted by a Presbyterian minister who had never met Pollock. (JP251)

Jackson's neighbour Conrad Marca-Relli later recalled that after the funeral he, Willem de Kooning, and some other guests were at his (Conrad's) home when Jackson's dogs appeared.

Conrad Marca-Relli:

"Jackson's dogs came into my house because they were looking for their master. It gave me the creeps. I said something and Bill said, 'It's all right. That's enough. I saw Jackson in his grave. And he's dead. It's over. I'm number one.' I said, 'Bill come on. This is something else.' (DK395)

Art dealer Eleanor Ward was also at Conrad's home at the time. De Kooning had gone into the garden and she had followed him. When she returned she told the others that de Kooning was crying. (DK396)

After the funeral Lee Krasner returned to her and Jackson's home in the Springs and then moved to Manhattan where she would remain for the next two years. As the executor (and the main beneficiary) of Jackson's will, she sold his paintings slowly, at high prices. The price for a Pollock painting rose quickly after his death. A friend of Krasner, John Little, would later comment "The three greatest dealers in the U.S.? Pierre Matisse, Leo Castelli and Lee Krasner." (JP253)

Around December 1955 Jackson's dealer Sidney Janis had tried to sell Pollock's Autumn Rhythm to the Museum of Modern Art for $8,000 but the offer had been rejected due to the high price. After Pollock's death Alfred Barr of MoMA rang Janis and asked him again about the picture. Janis conferred with Lee Krasner and wrote to Barr that Krasner was now asking $30,000 for the work. Barr was "so shocked" by the increase that he never answered Janis' letter. Instead the work was sold to the Metropolitan Museum. According to Janis, "We sold Autumn Rhythm almost immediately to the Metropolitan Museum for $30,000." (RO341) Pollock's high prices were also reflected in what dealers now got for the work other Abstract Expressionists. Janis recalled "we had a little less trouble selling a de Kooning for $10,000 than we had a month earlier trying to sell one for $5,000." (JP253)

c. November 1956: Donald Blinken buys Mark Rothko's Blue over Orange.

Blinken had previously purchased Rothko's Three Reds (1955) in May 1956. In 1958 he would also acquire Number 9, 1958 and in 1962 or 63, Number 117, 1961. When he purchased Blue over Orange in 1956, he also bought an untitled watercolour dated 1946. (RO639fn22)

Friday, November 30, 1956 at 9:30 p.m.: "An Evening for Jackson Pollock at The Club" takes place.

From Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible by B.H. Friedman:

... many of his [Pollock's] friends and admirers gathered to speak with some of the personal passion that was lacking at the funeral. The Club's postcard announced that "James Brooks, Willem de Kooning, Clement Greenberg, Rube Kadish, Frederick Kiesler, Franz Kline, Corrado di Marca-Relli and others will speak" and that Harold Rosenberg would be chairman. Though the announcement suggested a panel discussion, the evening had a much more informal character... Kadish spoke about their schooling in California, their early ideas about art, and Jackson's love of rocks, stones, elemental shapes.... Brooks recalled the years on the Project when he was particularly close to Jackson's brothers and then the years when Jackson used to stay with him and his wife at 46 East 8th Street and finally the purchase in 1949 of a place in Montauk from which, on Fridays for the next five summers or so, the Brookses would drive to East Hampton to take care of their shopping and laundry and sometimes to see a movie and almost always to have dinner with the Pollocks... Grace Hartigan repeated de Kooning's remark about Jackson's breaking the ice. Greenberg responded, "Broke the ice for whom?" suggesting that he thought de Kooning was not part of the same tradition as Pollock but more closely identified with Cubism. De Kooning explained that the had used a typically American phrase about a typically American guy, that he had not meant that Pollock's esthetic leadership was unique or exclusive but part of a moment in history, and that what Pollock had opened up was the recognition of American artists and a market for their work... Of the announced speakers Conrad Marca-Relli didn't appear, and Franz Kline was the only one of them who never said a word; he was [as] silent as Lee Pollock. (JF252-3)

December 19, 1956 - February 3, 1957: "Jackson Pollock" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

Originally planned as the inaugural exhibit of a series of exhibitions by artists in mid-career, the show became a memorial retrospective consisting of thirty-five paintings and nine watercolours and drawings from 1938 - 1956. (PP328)

Jackson Pollock's grave, Green River cemetery