American Expressionism 1950

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

Willem de Kooning: "Maybe... I was painting the woman in me. Art isn't a wholly masculine occupation, you know. I'm aware that some critics would take this to be an admission of latent homosexuality... If I painted beautiful women, would that make me a non-homosexual?"

1950: Barnett Newman makes his first sculpture.

The sculpture, Here 1, was made of wood and plaster. (MH)

1950: Robert Motherwell marries Betty Little. (HM)

January 10 - 30, 1950: "New Paintings by Adolph Gottlieb" at the Kootz Gallery. (AG173)

January 23, 1950: Barnett Newman's first solo exhibition opens at the Betty Parsons Gallery.

Tony Smith and Mark Rothko helped with the installation. Press response was generally negative and one of the paintings was vandalized. Thomas Hess wrote in Art News that "Newman is out to shock, but he is not out to shock the bourgeoisie - that has been done. He likes to shock other artists."

One painting sold - End of Silence - to a college friend of Newman's wife. After gallery deductions, Newman earned $84.14 from the sale. (MH)

During the same year (1950) Newman's work was also exhibited in "Post-Abstract Painting, 1950, France-America" at the Hawthorne Memorial Gallery in Provincetown, Massachusetts and in "American Painting" at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. (MH)

January 23, 1950: A party is held at the Club for Barnett Newman after his first one-man show at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (NE158)

January 27, 1950: The Museum of Modern Art acquires Number 1A, 1948 by Jackson Pollock. (PP324)

According to Deborah Solomon's biography of the artist, Jackson and his wife Lee Krasner attended a reception for the painting at the museum which was exhibited in January. (JP199)

January/February 1950: Barnett Newman exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (RO286)

February 2, 1950: "Party and Painting/Planning the Future" at the Club with speaker Harold Rosenberg. (NE158)

February 9, 1950: Film program at the Club with speaker Rudy Burckhardt. (NE158)

February 17, 1950: André Malraux's Voices of Silence symposium at the Club.

Robert Motherwell supported/ Barnett Newman opposed ("it was de Gaullism, making all art political") (NE158)

February-19 March 1950: "Seventeen Modern American Painters: The School of New York" exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

The exhibition would travel to the Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills, California from January 11 - February 7, 1951. It included Jackson Pollock's Number 3, 1949: Tiger (1949). Robert Motherwell wrote the preface for the catalogue. He titled the preface "The School of New York."

Robert Motherwell:

I mean ultimately at the end of 1949 and the beginning of 1950 I invented the term "School of New York." I was asked to write the preface to the first showing on the West Coast and in trying to find common denominators among the various people (including some people that we now would not regard as Abstract Expressionist), I realized that one couldn't make aesthetically a common denominator; but that what everybody did have in common in the sense that there was a School of Paris or in those days a Boston School of Jewish Expressionist painters, there was a New York School. But the word "New York" was meant in another sense. There is no such thing as Abstract Expressionism. They're a collection of individuals working with certain aspirations or whatever. (SR)

Milton Resnick:

Ad Reinhardt and Motherwell had decided to have a group of artists and call them the New York School. The first meetings were held at Ad Reinhardt's studio somewhere near NYU. There were like twenty people there. [Motherwell] said, 'There's no use having a New York school unless we know who you are.' Motherwell was a banker's son with a lot of influence at The Museum of Modern Art. He had power and connections. At that meeting, I couldn't believe it. I thought it was crazy to suggest that we could be a New York school... I wasn't saying much because I was thinking, 'This is a lot of shit.' But I did say something and Motherwell said, 'Milton, I couldn't have said that better myself.' That was the last straw. That son-of-a-bitch college boy thinks he knows something. So when we left I felt as if Bill and I were of the same mind... And I said 'That's the first time I heard about the pot of gold and the rainbow and the gold is right there to begin with.' So Bill said, 'You're a fucking nihilist. You don't want to be in.' We were standing in front of the Cedar Bar. And I said, 'You go in. I'm not going in with you.' That was the first time we saw differently. (DK304)

February 23, 1950: New Aesthetics/Talk on Dewey: America and Money Culture at the Club with speaker William Lipkind. (NE158)

1950: Mark Rothko exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery.

Eleven paintings were included ranging in price from $500 to $1,500, with the average price being about $1,100.00. (RO609)

1950: Elaine de Kooning meets Mark Rothko and Jeanne Reynal.

Elaine first met Rothko at parties.

Elaine de Kooning:

He's one of those people that once I knew him, I seem to have known him always... but I know I didn't seem always to have known him before 1950 and that was the advent of the Artists' Club [the Club]. It also was the year that I met Jeanne Reynal who was a mosaicist, a wonderful artist who was much better known as a collector, to the detriment of her reputation as an artist... Gorky was her big artist, but she also collected [Isamu] Noguchi and she had Mark Rothko and Barney [Barnett] Newman. I would meet Rothko at parties. Jeanne Reynal gave the most superb parties. She'd have perhaps 18 people and have drinks before dinner - wonderful, luxurious drinks - and wine with dinner and drinks after dinner. And the walls were covered with Gorkys and then she had a superb painting by Mark Rothko. And later she bought some paintings of Bill's [Willem de Kooning]. So I would meet him often at Jeanne Reynal's and also at the Artists' Club, and at parties of Yvonne Thomas's. Yvonne Thomas had a huge apartment up on Park Avenue and she also gave wonderful parties. So it was a great period for parties. Really scintillating, sparkling parties when the conversation was just absolutely wonderful. And Mark Rothko was very social, very smooth socially. He had kind of an aloof manner. He would stand up very straight with his head tilted back looking down and with a little archaic Greek smile on his face and make these dry little wisecracks. And I found him very witty and also a very attractive man. He had an atmosphere of sensuality that I found very appealing. So I would say I met him in 1950. (SE)

Rothko and Elaine became friends as a result of a letter she sent him after seeing an exhibition by him.

Elaine de Kooning:

I saw the first show, the breakthrough. His earlier work in the '40s that was influenced by [André] Masson and had those contours and had a tension to his work. But then when he came out with the first paintings of the floated-on areas, the turpentine washes where there were no contours and the edges were indistinct, one color floated over another. And I was absolutely captured by the magic of the presence of the colors, the fact that they did not inhabit shapes. That interested me very much. The shapes, they weren't really shapes. They inhabited areas and the areas were approximate. It was, to me, very enthralling. So I wrote Rothko a letter explaining my response to his work, and he told me that he was very touched by the letter, that it meant a great deal to him, that it was the most intelligent sense of a response that he had received to his paintings because, of course, they had been covered by critics. So from the day of that letter forth, we were fast friends. He was always very flirtatious with me. And his relation to certain women was one of - you know - the kind of flirtation that's not intended to lead anywhere, but up in the air is that sense of, wouldn't it have been wonderful? (SE)

When asked to compare Rothko's persona with that of Arshile Gorky, Elaine thought Rothko had a "very healthy self-worship:"

Elaine de Kooning:

... they [Arshile Gorky and Mark Rothko] were very different. Gorky had a role in mind that he played, but Rothko was hypnotized by his own role and there was just one. The role was that of the Messiah - I have come; I have the word. I mean, Rothko had a very healthy self-worship and he did feel that he had discovered some great secret. He felt that this was of universal import. Gorky in one way seemed more arrogant, but on the other hand, Gorky also had streaks of humility. He had tremendous reverence for other artists. Rothko became totally involved in his own mythology, more than anyone I know except Barney Newman. They both were tremendously involved with their self-image. (SE)

1950: Clyfford Still returns to New York.

Still left the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco where he was teaching and returned to New York. (RO223)

c. February 1950 - January 1951: Emmanuel Navaretta lives with Franz Kline for approximately eleven months.

Kline refused to take rent from Navaretta and gave him the bed, with Kline sleeping on the couch. (FK178)

February 28 - March 20, 1950: "Black or White: Paintings by European and American Artists" at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery.

Included Robert Motherwell.

March 2, 1950: "Modern Style" at the Club with speaker Heinrich Blücher.

Blucher was married to Hannah Arendt who was a friend of Willem de Kooning. (NE158)

March, 1950: Jackson Pollock begins painting Untitled (Mural) for the Geller House in Lawrence, Long Island. (PP324)

March, 1950: Jackson Pollock's therapist dies.

Dr. Edwin Heller died in a car accident ending his successful treatment of Pollock's alcoholism. (PP324) In November Jackson started drinking again, ending the longest period of sobriety he would have as an adult.

March 25, 1950: "Spatial Form in Modern Literature" at the Club with speaker Joseph Frank.

March 28 - April 24, 1950: "Selected Paintings by the Late Arshile Gorky" exhibition at the Kootz Gallery. (AG50fn4)

Adolph Gottlieb wrote the introduction to the exhibit.

Adolph Gottlieb [from the introduction]:

For him [Gorky], as for a few others, the vital task was a wedding of abstraction and Surrealism. Out of these opposites something new could emerge, and Gorky's work is part of the evidence that this is true. (AG29)

March 29, 1950: Mark Rothko, recovering from a "breakdown," leaves New York for a five month tour of Europe. (RO283)

From Mark Rothko: A Biography by James E.B. Breslin:

[Rothko] traveled to Europe partly to recover from what Annalee Newman described as his "breakdown" of 1949. Mrs. Newman thought Rothko's collapse occurred because her husband's Betty Parsons exhibit in January/February of 1950 established that 'he had found what he was looking for but Rothko had not." Actually, Rothko had found what he was looking for and had exhibited sixteen of his new paintings at Parsons in the show immediately preceding Newman's. Rothko's depression had more to do with the death of his mother than the progress of Newman's art. But it is quite possible Rothko was disturbed by the first public showing of Newman's "zip" paintings, since Newman, hitherto the polemical spokesman for his painter-friends, had suddenly emerged as their equal and rival. Still, the five letters Rothko wrote to the Newmans from Europe sound friendly enough, and Rothko's depression before leaving - also recalled by Robert Motherwell - likely resulted from a variety of personal and social tensions that came with his new importance in the art world. (RO286)

Rothko's mother had died about a year and a half before his European trip - in October 1948. In March 1949 Rothko had shown his multiforms at Parsons' gallery.

Rothko and his wife, Mell, spent three weeks in Paris, three weeks in the South of France in Cagnes-sur-Mer, eight or nine days in Venice, four weeks in Italy (Florence, Arezzo, Siena, Rome), returned to Paris for two weeks and then went on to London for three or four weeks. (RO283-4) Writing to Barnett Newman on April 17, 1950, Rothko gave his opinion of Paris: "The city is extremely engaging to the eye in 2 respects because of the grandeur, largeness and abundance of monuments which are the more impressive because of their ugliness - and then the many streets and alleys in which crumbling paster and dangling window shutters form a continuous pastiche of textures. A street of buildings in good repair is unendurable. But morally one abominates a devotion to such decay and to the monuments which commemorate nearly everything which I, and France, too much abhor." (RO284) Later, in 1956, Rothko would comment, "I traveled all over Europe and looked at hundreds of Madonnas but all I saw was the symbol, never the concrete expression of motherhood." (RO285)

March 30, 1950: "On Marino Marini" at the Club, sponsored by Willem de Kooning. (NE158)

The evening was a homage to Marini whose statue of a horse and rider had recently beeen purchased by the Museum of Modern Art.

April 10, 1950: "On Buckminster Fuller" at the Club, sponsored by Harry Holtzman. (NE158)

An informal evening and party.

April 12, 1950: "Mozart recordings" at the Club with speaker Max Margulis. (NE159)

April 13, 1950: A talk on Paris at the Club with speaker K. Costello.

April 15, 1950: Mark Rothko's Number 8, 1949 appears in Vogue magazine.

In an article discussing the "many-picture wall" versus the "one-picture" wall, the "one-picture" wall was represented by a full page photograph of Rothko's work which "not only dominates the wall (it is eight feet high by five feet wide), but animates the whole room with a glowing sense of space and light and liberated shapes." (RO302/SG204/248n31)

April 1950: A symposium on the new art is held at Studio 35.

The three day symposium at Studio 35, "Modern Artists in America," was organized by Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt. Among the people attending were Alfred Barr from the Museum of Modern Art, David Smith, Ralph Rosenborg, James Brooks, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, Willem de Kooning and Milton Resnick. One of the topics covered was what to call the bourgeoning abstract art movement in New York. Names suggested included Abstract-Expressionist, Abstract-Symbolist, Abstract-Objectionist. Brooks thought that 'direct' or 'concrete' art might be a 'more accurate' term for the art being produced. De Kooning commented, "It is disastrous to name ourselves." (DK304-5)

It was at the end of the symposium that Adolph Gottlieb suggested that the artist protest the juries selected for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's national contemporary art competition. (RO271) An "open letter," written mainly by Adolph Gottlieb (and hand delivered to The New York Times by Barnett Newman (IS28)) was produced, signed by fourteen painters at the symposium (including Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Hedda Sterne and Theodoros Stamos), plus four additional painters (including Jackson Pollock and apparently Mark Rothko who was in Europe at the time). (RO271) [Note: According to art writer, Irving Sandler, the letter was "signed by eighteen painters and supported by ten sculptors." (IS28)]

Newman had rung Pollock in the Springs not long after the painter had left New York. Krasner answered the phone and at first told Newman that he was in the barn he used as a studio and couldn't be disturbed. Newman told her it was urgent. He was ringing from Adolph Gottlieb's apartment on State Street in Brooklyn where he was meeting with Rothko, Reinhardt and others to finish drafting the letter of protest. Although Krasner was angry that they had not asked her to sign the letter, as she was an artist too, she got Jackson who sent a telegram the same day expressing his support: "I endorsed [sic] the letter opposing the Metropolitan Museum of Art 1950 juried show." (JP202)

April 20, 1950: "Psychology and the Artist" at the Club with speaker Paul Goodman. (NE159)

April 27: "The Oppositions of Sensibilities and Subject Matter" at the Club with speaker Thomas B. Hess.

Philip Pavia: "Hess predicted that the Club would collapse from so much conflict." (NE159)

Late April - May 1950: "Talent 1950" exhibition at the Kootz Gallery.

(Howard Devree, "American Roundup; Four Group Shows of Contemporary Art In Its Variety - Tamayo's Painting," The New York Times, April 30, 1950 (Sunday), Section: Drama-Music, Fashion-Screen, p. X8)

The exhibition featured one work each by twenty-three artists chosen by Clement Greenberg and Meyer Schapiro. It included work by Robert Goodnough, Larry Rivers, Esteban Vincente, Friedebald Dzubas (aka Friedel Dzubas), Harry Jackson, Alfred Russell, Elaine de Kooning and Franz Kline.

(FK88)

Greenberg would later comment "We rescued Kline." Greenberg thought "his paintings were bad, but he did good drawings." John Ferren who lived in the same building as Kline later recalled Kline's surprise that Greenberg liked his black and white work. (FK88)

May 6, 1950: Mark Rothko writes to Richard Lippold inquiring about a job. (RO287)

Rothko wrote to Lippold from Cagnes-sur-Mer inquiring about "an opening in your school" in Trenton, New Jersey. In his letter he wrote that "certain developments in our circumstances" (probably a reference to Mell's pregnancy) had made it necessary for him to look for a teaching job, noting that "I have long thought it the best solution for the artist." (RO287) Rothko did not get a position at Lippold's school, but would be offered an assistant professorship at Brooklyn College in December (see December 1950 and February 1951).

May 11, 1950: "New Directions" at the Club with speaker Samuel Kootz. (NE159)

May 18, 1950: "Culture and Belief" with speaker Father Lynch, introduced by Robert Motherwell.

Philip Pavia (describing the evening): "Organized religion and art. Must art have a social union? Very popular speaker, and friend of art dealer John Myers." (NE159)

May 22, 1950: Artists protest the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the The New York Times.

(Note: A footnote in Jackson Pollock, published by The Museum of Modern Art, indicates that the letter "was excerpted in the May 21, 1950" issue of The New York Times. (PP329 fn33). It was actually the May 22nd issue.) ("18 Painters Boycott Metropolitan; Charge 'Hostility to Advanced Art'," The New York Times, May 22, 1950)

The article was headlined "18 Painters Boycott Metropolitan; Charge 'Hostility to Advanced Art.'"

As detailed in the article, the open letter to Roland L. Redmond, the president of the Metropolitan protested that the jurors selected for the December exhibition were "notoriously hostile to advanced art" and the choice of jurors "does not warrant any hope that a just proportion of advanced art will be included." The letter proclaimed "The undersigned artists reject the monster national exhibition to be held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art next December, and will not submit work to its jury," adding "We draw to the attention of those gentlemen the historical fact that, for roughly a hundred years, only advanced art has made any consequential contribution to civilization." The group also picketed the museum. (DK305)

The letter continued: "We draw to the attention of those gentlemen the historical fact that, for roughly 100 years, only advanced art has made any consequential contribution to civilization."

The artists who signed the letter were: Jimmy Ernst, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Hans Hofmann, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Richard Pousette-Dart, Theodoros Stamos, Ad Reinhardt, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Willem de Kooning, Hedda Sterne, James Brooks, Weldon Kees and Fritz Bultman. Sculptors who signed the letter were Herbert Ferber, David Smith, Ibram Lassaw, Mary Callery, Day Schnabel, Seymour Lipton, Peter Grippe, Theodore Roszak, David Hare and Louise Bourgeois.

Barnett Newman told the journalist for The New York Times that although they were critical of the membership of the five regional juries they were specifically opposed to the New York group, the "national jury of selection" and the "jury of awards."

The New York group of jurors were Charles Burchfield, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Leon Kroll, Ogden Pleissner, Vaclav Vytlacil and Paul Sample. The national jury consisted of Mr. Hale, Mr. Pleissner, Maurice Sterne, Millard Sheets, Howard Cook, Lamar Dodd, Francis Chapin, Zoltan Sepeshy and Esther Williams. The jury of awards included William M. Milliken, Franklin C. Watkins and Eugene Speicher.

First prize was $3,500, second $2,500, third $1,500 and fourth $1,000.

May 23, 1950: The New York Herald Tribune attacks "The Irascible Eighteen" for "distortion of fact."

The protest letter sent to The New York Times was also covered in articles in The Nation, Art News, Art Digest and Time. (RO271) Life magazine became involved. They sent a photographer to photograph "The Irascible Eighteen" on November 26th. Jackson Pollock came down to Manhattan to participate in the photo session. (JP202)

Spring 1950: Willem de Kooning paints Excavation.

According to de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, de Kooning began painting Excavation in "early spring of 1950" (DK293) and completed it "in May 1950." (DK305).

Summer 1950: Mark Rothko refuses to provide a self-statement for The Tiger's Eye and the Magazine of Art.

In August (presumably from Europe) Mark Rothko wrote to Barnett Newman giving his reasons for his refusal to provide the statements: "I have nothing to say in words which I would stand for. I am heartily ashamed of the things I have written in the past. This self-statement business has become a fad this season." (RO241) Rothko had contributed an untitled artist's statement in the October 15, 1949 issue of Tiger's Eye. (RO607fn26)

June 1, 1950: Mark Rothko's wife find out she's pregnant. (RO287)

The child would be Rothko's first. The pregnancy was confirmed in Rome. On June 30th he wrote to Barnett Newman, "We are so happy about it, so happy, that we are leaving the practical considerations until we reach home." (RO287)

June 1, 1950: Hans Arp (in person) at the Club, introduced by Robert Motherwell. (NE159)

June 8, 1950: "Painter as Editor" at the Club with speaker John Stephan (co-editor of Tiger's Eye with his wife Ruth).

Philip Pavia: Stephan was a "leader of the Surrealists [who] brought in ideas of the oriental and Zen." (NE159)

June 1950: Willem de Kooning begins Woman I .

Woman I was not the first "Woman" that de Kooning painted - there had also been a Woman in c. 1944, a Woman in 1948, and various other "Woman" paintings during his lifetime.

According to de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, "In June 1950, not long after sending Excavation to Venice, de Kooning placed two seven-foot-high sheets of paper on the painting wall of his Fourth Avenue studio and began the drawings that would lead to one of the most disturbing and storied paintings in American art, Woman I." (DK309) The work would not be completed by de Kooning until 1952.

From de Kooning An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

With Woman I, de Kooning, emboldened by his abstract works, reopened his attack on half-buried problems, both formal and emotional. While painting Excavation, he had become fascinated with Mesopotamian figures, themselves excavated from the distant past, and with other ancient deities. "I had seen a picture of a Mexican goddess," he said, "to whom hearts were sacrificed." Such an image seemed to him contemporary as well as ancient, a powerful Everywoman of many guises. Following upon the great success of Excavation, de Kooning became haunted by her shifting countenance... Woman I, like his earlier figures, came to him in pieces. If he liked one section that he thought did not work with the rest of the composition, for example, he continued his practice of using charcoal to trace its forms onto thin paper, which he would then attach to a different part of the canvas to see how it looked. Or he might retain the tracing for later use. Sometimes he would paint over the attached tracing, experimenting with color and form.. The struggle with Woman I stretched into the fall of 1950... and extended into the spring of 1951. (DK309-11)

Willem de Kooning:

Maybe... I was painting the woman in me. Art isn't a wholly masculine occupation, you know. I'm aware that some critics would take this to be an admission of latent homosexuality... If I painted beautiful women, would that make me a non-homosexual? I like beautiful women. In the flesh - even the models in magazines. Women irritate me sometimes. I painted that irritation in the Woman series. That's all. (CW102)

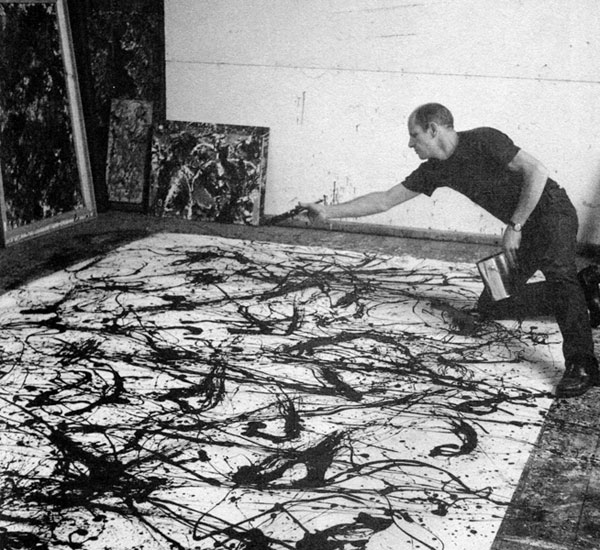

June 1950: Jackson Pollock is photographed painting for Art News - sort of.

Jackson Pollock pretending to paint Number 32, 1950

(Photo: Rudy Burckhardt)

Art News was planning a feature story - "Pollock Paints a Picture," with the object being to follow the making of a painting from the first stroke to the last. Pollock had promised, by telephone, to create a painting in the presence of a writer and photographer. Robert Goodnough and photographer Rudy Burckhardt visited Pollock in his studio. A painting he had already started (later to be titled Number 32, 1950) was lying on the floor of the barn he used as a studio. "I can't decide whether this painting is finished" he commented. He picked up a brush and told Burckhardt, "I'll pretend I'm painting." He pretended to paint the large canvas (approx. 9 ft. high and 15 ft. long) while Burckhardt photographed him moving a dry brush across the canvas. (JP206)

c. June 8, 1950: Bruno Alfieri compares Jackson Pollock to Picasso in L'Art Moderna. (PP329fn39)

The article was titled "Piccolo discorso sui quadri di Jackson Pollock (con testimonianza dell'artista)" (approx. translation: Small discourse on the pictures of Jackson Pollock (with testimony of the artist). (PP324/PP329fn39)

Pollock couldn't understand Italian but was impressed by the fact that Alfieri used his name and that of Picasso in the same sentence: "E al confronto di Pollock, Picasso, il povero Pablo Picasso... diventa un quieto e conformista pittore del passato." (Picasso compared to Pollock seemed like a quiet conformist, a painter out of the past.)

The rest of the article was less positive. Time magazine used the negative comments from the article in a news item on November 20, 1950 (see below).

June 8 - October 15, 1950: Alfred Barr chooses Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning (Excavation) and Arshile Gorky for the Venice Biennale. (PP324)

Six artists were chosen to participate in an exhibition of younger American painters in the U.S. Pavilion to accompany a retrospective of John Marin. Barr chose Willem de Kooning (Excavation), Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock. Pollock showed three paintings - Number 1A, 1948; Number 12, 1949; and Number 23, 1949. Alfred Frankfurter, editor of Art News at the time, chose the other three artists - Hyman Bloom, Rico Lebrun and Lee Gatch. (Gatch had exhibited as part of The Ten in their second exhibition at the Montross Gallery which took place December 14, 1936 - January 2, 1937.)

When Barr explained his choices in the June 1950 issue of Art News, he noted that "several names have ben used to describe this predominant vanguard: 'symbolic abstraction,' 'abstract expressionism,' 'subjectivism,' 'abstract surrealism.'"

Aline Louchheim, reporting on the Biennale, complained in the September 10th issue of The New York Times that "Europeans do not bother to give our pavilion very serious consideration." Although Marin had "received passing praise" Louchheim noted that "even the most intelligent critics... spent little time looking at Gorky and de Kooning." Pollock was "a special case." According to Louchheim his "detailed description of how he works (dripping paint, etc. on to canvas spread on the floor) has been assiduously translated and is grounds for violent arguments pro and con all abstract and automatic art." (JF155)

June 22, 1950: "Existentialism" with speaker Professor William Barrett of NYU.

Philip Pavia described the event as a "tough evening." (NE159)

Summer 1950: Jackson Pollock, Tony Smith and Alfonso Ossorio discuss a Catholic Church.

Pollock, Smith and Ossorio discussed the design and construction of a Catholic church to be built on Long Island at various times through 1952, but the plan was never realized. (PP324)

July 1, 1950: Jackson Pollock meets Hans Namuth. (JP207)

Pollock was at the opening of the exhibition "Ten East Hampton Abstractionists" at the the Guild Hall in East Hampton. Included in the show were works by Pollock, Lee Krasner, James Brooks, John Little, Wilfred Zogbaum, Buffie Johnson and other artists who had moved to the area. Namuth, a photographer from Harper's Bazaar, introduced himself and told him that he was renting a house for the summer in Water Mill. Namuth told Jackson he admired his work and would like to photograph him although not necessarily for Harper's Bazaar. Jackson agreed to do it. When Namuth rang the following week to make an appointment, Jackson promised Namuth that he could photograph him starting and possibly finishing a painting, just as he had promised Art News earlier in the year. When Namuth arrived Pollock told him that the painting was actually finished and that he did not plan to do any more work that day. Namuth asked if he could see Pollock's studio and Pollock and Krasner took him into the studio. A still-wet large painting was lying on the floor. Namuth viewed the canvas through his viewfinder and suddenly Pollock picked up a brush and started to paint. Namuth started shooting - the session lasted about half an hour with Namuth photographing Pollock as he was painting.

When Namuth brought the developed photos to Pollock the next weekend, Pollock asked if he had more. He didn't. So, throughout the summer Namuth returned to the Springs on the weekends to take more photographs. (JP208-9) He ended up taking 200 photographs of Pollock working on One: Number 31, 1950 and Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950. (PP324/PP329fn36) The photographs would be published in 1951.

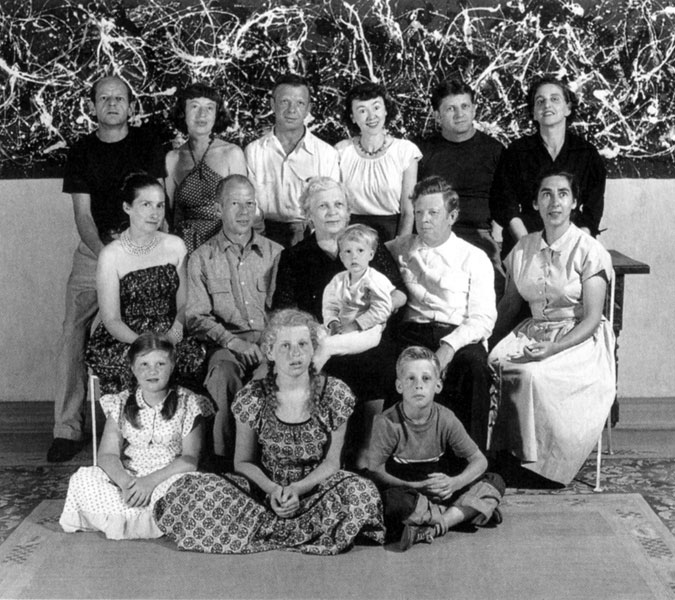

July 1950: The Pollocks have a family reunion in the Springs.

The Pollocks. The Springs 1950. In front of Number 2, 1949.

(Photographer unknown)

Jackson's mother arranged the reunion after she found out that her son Frank, a rose grower, would be traveling to New York from California to attend a convention. Jacksons's other brothers - Charles, Jay and Sande also attended. Charles had become an art professor, Jay a printer and Sande was living with his mother Stella. It was the first time in seventeen years that the family had a get-together. (JP203)

During their stay Pollock seemed obsessed with the article in L'Art Moderna which had compared him to Picasso. While the family socialized in the living room, Pollock stayed in the kitchen pouring over the article. When one of his relatives came in he would ask if they spoke Italian. His sister-in-law, Alma, asked "Is Picasso more important than your family?" Pollock and Krasner gave her a dirty look. When Jackson's brother Frank said casually that he was thinking of staying another day, Krasner reminded Jackson (out loud) that Betty Parsons was coming the following day. It was the last reunion the family would have. (JP204)

July 6, 1950: "Platonism: The Idea of Beauty" at the Club with speaker Father Lynch. (NE159)

July 20, 1950: "Club evening/Members only" at the Club. (NE159)

July 22 - August 12/15, 1950: Jackson Pollock exhibition in Venice.

The solo exhibition from Peggy Guggenheim's collection of Pollock's work ran at the Museo Correr in Venice while the Biennale was also taking place. Pamphlets and publications about the exhibition give two ending dates - August 12 on some and August 15 on others. (PP329n37)

Twenty paintings, two gouaches, and one drawing by Pollock were shown, including Alchemy, Croaking Movement, Enchanted Forest, Eyes in the Heat, Full Fathom Five, The Moon Woman, Reflection of the Big Dipper, Sea Change, Two, and The Water Bull. (PP324) The Water Bull and Reflection of the Big Dipper had been given by Guggenheim to the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam which lent them for the show. (PP329n38)

A smaller version of the show traveled to the Galleria d'Arte del Naviglio, Milan. (PP324)

August 1950: Franz Kline gets a job as an art instructor at a summer resort.

David Orr got Kline the job of speaking on contemporary art to guests at the Schroon Crest resort at Schroon Lake near Pottersville, New York. He received room and board and had use of a small studio but was not paid a salary. (FK178)

August 1950: Barnett Newman moves to a new studio.

The new studio, located at 110 Wall Street, enabled him to work on larger canvases. (MH)

August 5, 1950: The New Yorker publishes an interview with Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. (PP324/5)

Berton Roueché [from "Unframed Space," The New Yorker (August 5, 1950)]:

We improved a shining weekend on eastern Long Island by paying a call on Jackson Pollock - an uncommonly abstract abstractionist and one of seven American painters whose work was tapped for inclusion in the Twenty-fifth International Biennial Exhibition of Figurative Arts, now triumphantly under way in Venice... Pollock, a bald, rugged, somewhat puzzled-looking man of thirty-eight, received us in the kitchen, where he was breakfasting on a cigarette and a cup of coffee and drowsily watching his wife, the former Lee Krasner... as she bent over a hot stove, making currant jelly. Waving us to a chair in the shade of a huge potted palm, he remarked with satisfaction that he had been up and about for almost half an hour. It was then around 11:30 A.M. "I've got the old Eighth Street habit of sleeping all day and working all night pretty well licked," he said. "So has Lee. We had to, or lose respect of the neighbors. I can't deny, though, that it's taken a little while. When'd we come out here, Lee?" Mrs. Pollock laughed merrily. "Just a little while ago," she replied. "In the fall of 1945."

"It's marvelous the way Lee's adjusted herself," Pollock said. "She's a native New Yorker, but she's turned into a hell of a good gardener, and she's always up by nine. Ten at the latest. I'm way behind her in orientation. And the funny thing is I grew up in the country. Real country - Wyoming, Arizona, northern and southern California. I was born in Wyoming. My father had a farm near Cody. By the time I was fourteen, I was milking a dozen cows twice a day." "Jackson's work is full of the West," Mrs. Pollock said. "That's what gives it that feeling of spaciousness. It's what makes it so American."

Autumn 1950: "Young Painters in the U.S. and France" at the Sidney Janis Gallery.

The exhibition, which Janis worked on with Leo Castelli, paired American artists with French ones. De Kooning's Woman (1949-50) was paired with Jean Dubuffet's L'Homme au chapeau bleu (1950). Jackson Pollock was paired with Lanskoy, Mark Rothko with de Staël and Kline with Soulages.

Leo Castelli:

I came to know Sidney Janis in the late forties, and we saw quite a lot of each other. In 1950 we did a show together that paired postwar French and American painters who seemed to have something in common: de Kooning and Dubuffet (their figures of women), Gorky and Matta, Kline and Soulages, Pollock and Lanskoy, Rothko and de Stael, and some others. The show was a bit silly, and purists like Charlie Egan, the dealer who handled de Kooning, took a very critical view. It proved one thing, however, that there really was no connection, except on a very superficial level, between European and American painting. (AD85)

Late August 1950: Mark Rothko returns to the U.S. from his European trip. (RO286)

Autumn 1950: Willem de Kooning teaches at Yale.

Josef Albers had become the head of the design department at Yale after leaving Black Mountain College in 1949. He asked de Kooning to come to Yale as the "visiting critic in painting at the School of Fine Arts and Architecture." De Kooning, who would later describe himself as more of a "song-and-dance man" than "an academic" was paid $1,600 for his teaching stint. At the first class some of the students mistook de Kooning for the janitor. Robert Jonas later recalled that de Kooning apparently told one student "You think because your father is rich, culture is going to stick to your ass" and told Albers "These guys are so lousy. Why don't you flunk them?" Albers replied "If they were plumbers or carpenters I would. But they're just painters. they can't do any harm to anyone." The following year, however, de Kooning would write to Albers that he "developed so large a sentiment for the place [Yale]... partly because I never got anything like that in my own youth." Although Albers offered de Kooning a chance to continue teaching after his period of "visiting critic" was over, de Kooning (who pronounced "Yale" like "jail" with his Dutch accent) declined, encouraging him instead to hire Franz Kline who needed the money. (DK307-8/659)

1950: Robert Motherwell joins the graduate faculty at Hunter College.

Motherwell would teach at Hunter College until 1958. (HM)

September 2 - 3, 1950: Hans Namuth begins filming Jackson Pollock painting.

At the end of the summer when Namuth was visiting Pollock's studio on the weekends to photograph him, Namuth came up with a new idea - to film Pollock with a movie camera while he painted. Pollock agreed to the idea and Namuth arrived during the first weekend in September with his wife's Bell and Howell Turret. Namuth showed the seven minutes of footage he shot to a film editor friend, Paul Falkenberg, who suggested that Namuth make a color film and offered to help him get the two thousand dollars to fund it. The color film required lighting and since the barn that Pollock used as a studio did not have any electricity, Pollock offered to work outside. Although he had finished the paintings he was doing for his upcoming show at the Betty Parsons Gallery, Jackson offered to paint one more painting which they could film.

Namuth suggested that Pollock start a new painting, only this time to paint it on glass secured a few feet off the ground so that Namuth could film from underneath the glass. According to most published accounts, it was Namuth who came up with the idea of painting on glass. Lee Krasner wasn't so sure. When an interviewer (Barbara Rose) later noted that it was Namuth's idea, Lee responded "Was it? I was there while Pollock painted it, certainly. But I wasn't there when Namuth suggested that he paint on glass. As far as I'm concerned, Jackson got a sheet of glass, and decided to paint on it, and Namuth photographed it... The first I heard of it, Pollock showed me a piece of glass. When I asked him what it was for, he said he wanted to try to paint on it. As you know, he was constantly experimenting. I always thought he got the idea of painting on glass from Duchamp." (BP ) During four consecutive weekends Namuth filmed Jackson outside working on the painting. According to Deborah Solomon in Jackson Pollock: A Biography, Pollock "destroyed the painting." (JP211) According to the chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock, the work was Number 29, 1950. (PP325)

In a radio interview conducted in Jackson Pollock's studio in late 1950, Pollock is asked about a work "done on plate glass" in the corner of the studio and the artist responds, "Well that's something new for me. That's the first thing I've done on glass and I find it very exciting. I think the possibilities of using painting on glass in modern architecture - in modern construction - terrific." (IP)

On November 25, 1950 - the Saturday after Thanksgiving, Namuth finished filming Pollock.

October 13, 1950: Open house party for Jeanne Reynal at the Club. (NE160)

October 16, 1950: Exhibition of mosaics by Jeanne Reynal opens at the Hugo Gallery.

("British Art Work to Have Exhibition; Display Opening Wednesday at Knoedler's Includes Oils, Water-Colors Since 1850," The New York Times, October 16, 1950, section: Amusements, p. 40)

October 16 - November 4, 1950: Franz Kline's first one-man show in New York.

Kline's first one-man show in New York took place at the Egan Gallery located at 63 East 57th Street. Kline designed the four page brochure for the exhibition. Emmanuel Navaretta who shared Kline's loft for about eleven months in 1950, recalled that Kline struggled with the brochure spending hours lettering his own name and complaining to Navaretta that "I haven't got a signature." Kline had struggled previously with his signature. His wife later recalled that he had trouble with his signature while living in England, as well. (FK93/FK170n31)

Elaine de Kooning contributed a statement about Franz Kline for the brochure but it was not included. The brochure was too small and it would have been too expensive to produce a larger one. Part of her statement was included in the exhibition catalogue for the "12 Americans" exhibition in 1956 at the Museum of Modern Art. (FK170n31)

The exhibition at Charles Egan's gallery included eleven abstractions in mostly black and white. (Two of the paintings had colour - brown underpainting near the bottom of Nijinsky and traces of green in Leda.) Paintings included Chief, Cardinal, Clockface, High St., Wyoming, Nijinsky, Giselle, The Drum and Wotan. (FK87/FK93/95) In addition to Kline's paintings the show included a small amount of untitled drawings and studies priced at $50 to $100. David Orr backed the show with a $300 grant to Kline. (FK88)

Harry F. Gaugh [Kline biographer]:

Kline's 1950 abstract paintings were based on drawings made on pages of telephone books. He used these, rather than drawing paper, because they could be picked up for nothing. (Robert Goldwater pointed out that the print pattern on these pages "prevents any mistaken perspective recession"' perhaps another reason Kline liked them.) From time to time Kline looked through these telephone-book drawings, which were stacked by the hundreds in a corner. Selecting one that he felt would work as a painting, he pasted it to a piece of cardboard. Then, either tacking the drawing beside a canvas or holding it, he followed it closely, painting directly. An image was usually not transferred with any grid system. One painting in his 1950 show, High St., may have passed through a grid stage as indicated by a drawing on graph paper, but it began as a telephone-book sketch and remains closer to it than to the slightly attenuated and more refined graph paper example. (FK90)

According to Kline's biographer, Harry F. Gaugh, the de Koonings, Charles Egan and Emmanuel Navaretta helped to name the paintings, including Hoboken. According to Navaretta, Kline and himself would sometimes go to Hoboken to eat fish and Kline liked the name. According to Elaine de Kooning, there was an eight hour naming session with Kline, the de Koonings and Egan "in a spirit of levity with a bottle of Scotch on the table." Elaine recalled that Chief and Cardinal were names of trains that Kline remembered. Navaretta later recalled that Clockface referred to the clock at Wanamaker's Department Store. (FK93)

Irving Sandler:

Franz invited the de Koonings to help him title the pictures in his first show. They all had to agree. Franz decided to call one work Chief, named after a Lehighton locomotive, but Elaine persuaded him that the name would go better with the canvas that now bears the title. That was the painting that was responsible for my first epiphany in art. (IS59)

Manny Farber reviewed Kline's exhibition in The Nation magazine (November 11, 1950):

Manny Farber [from The Nation review]:

[Franz Kline] achieves a malignant shock that is over almost before it starts. The first impression... is refreshing. A heroic artist achieves a Wagnerian effect with an almost childish technique. It is the blunt, awkward, ugly shape that counts, not finicky detailing or complication. But these yawning white backgrounds and hulking black images hide a humble rather than a primitive craftsmanship, clever at making facetious emotion appear morbidly violent and suave brushing seem untrained. (FK96)

Two paintings were sold from the exhibition - Chief and Leda. Art Collector David M. Solinger purchased Chief for The Museum of Modern Art. (The museum officially accepted the painting on January 22, 1952.) Leda was purchased by G. David Thompson. (FK95/FK171n40)

October 16, 1950: Party for Franz Kline after his opening at the Charles Egan Gallery.

Philip Pavia described Kline's opening as "the most important show of the year." (NE160)

October 21, 1950: Guitar concert at the Club by Julio Prol. (NE160)

October 23 - November 11, 1950: "Young Painters in U.S. & France" exhibition takes place at the Sidney Janis Gallery. (PP325)

Jackson Pollock showed Number 8, 1950. (PP325)

October 23, 1950: Opening party for Louise Bourgeois at the Club. (NE160)

October 28, 1950: Edgard Varèse speaks at the Club. (NE160)

November 3, 1950: "Heidegger and Existentialism" at the Club with speaker Egon Viotta. (NE160)

November 10 - December 31, 1950: Whitney Annual.

Included Jackson Pollock's Number 3, 1950. (PP325)

November 14 - December 4, 1950: "Motherwell: First Exhibition of Paintings in Three Years" at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery.

November 14, 1950: Party for Robert Motherwell at the Club after his opening at Kootz. (NE160)

November 20, 1950: Jackson Pollock appears in Time magazine.

The news item was titled "Chaos, Damn It!" and noted that "The Museum of Modern Art's earnest Alfred Barr, who picked Pollock, among others, to represent the U.S. in Venice's big Biennale exhibition last summer, described his art simply as "an energetic adventure for the eyes." It also quoted negative comments made by Critic Bruno Alfieri in L'Art Moderna about Pollock's paintings shown earlier in Venice (see above).

Bruno Alfieri [quoted in Time from his article in L'Art Moderna]

It is easy," Alfieri confidently began, "to describe a [Pollock]. Think of a canvas surface on which the following ingredients have been poured: the contents of several tubes of paint of the best quality; sand, glass, various powders, pastels, gouache, charcoal ... It is important to state immediately that these 'colors' have not been distributed according to a logical plan (whether naturalistic, abstract or otherwise). This is essential. Jackson Pollock's paintings represent absolutely nothing: no facts, no ideas, no geometrical forms. Do not, therefore, be deceived by such suggestive titles as 'Eyes in Heat' or 'Circumcision'. . . It is easy to detect the following things in all of his paintings:

Chaos.

Absolute lack of harmony.

Complete lack of structural organization.

Total absence of technique, however rudimentary.

Once again, chaos.But these are superficial impressions, first impressions . . . Each one of his pictures is part of himself. But what kind of man is he? What is his inner world worth? Is it worth knowing, or is it totally undistinguished? Damn it, if I must judge a painting by the artist it is no longer the painting that I am interested in . . .

(Time magazine, November 20, 1950)

An angry Pollock sent a telegram to Time which was reprinted in its December 11th issue:

Jackson Pollock [telegram to Time]:

No chaos damn it. Damn busy painting as you can see by my show coming up Nov. 28. I've never been to Europe. Think you left out the most exciting part of Mr. Alfieri's piece." (JP205)

For Jackson, the "most exciting part" of the piece was the bit that compared Pollock to Picasso.

November 24, 1950: "American versus French Art" at the Club.

According to Philip Pavia the evening's theme was also the theme of a Sidney Janis exhibition. Speakers were Theodore Brenson, Nicolas Calas, Clement Greenberg, Frederick Kiesler and Andrew Richie. (NE160)

November 25, 1950: Jackson Pollock starts drinking again. (PP325)

On the Saturday after Thanksgiving, Hans Namuth finished filming Jackson Pollock outdoors while he painted on glass. After the filming was finished Pollock went into the kitchen and poured out two drinks: "Hans, come have a drink with me." Namuth walked into the kitchen followed by a guest, Alfonso Ossorio, and Lee Krasner. Jackson had one drink and then didn't stop. He pulled off a string of cowbells hanging in the kitchen doorway and threatened to hit his guests with it. Lee suggested sitting down for dinner. Pollock started insulting Namuth at the dinner table and then suddenly picked up the table sending the roast beef to the floor. Lee washed off the roast beef and returned it to the table. Pollock picked the table up a second time, again causing the dishes to fly off it. "Coffee will be served in the living room," Lee announced. Pollock left the house and drove away in his car. (PP325/JP212)

November 26, 1950: The Irascibles sit for their Life magazine photo session. (RO273/JP202/PP325)

The Life article was conceived after the group of artists who were labeled "the irascibles" protested the Metropolitan's "American Art Today" exhibition in the May 22, 1950 issue of The New York Times (see above.) The article was timed to coincide with the Met's exhibition. Life originally wanted the artists to pose on the steps of the Met but they refused and, instead, were photographed in a studio on West 44th Street. The photographer was Nina Leen. (RO273) 12 photographs were taken of 15 of the 18 artists who had signed the protest letter to the Times. (RO272) Artists in the photo were: Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, Ad Reinhardt, Hedda Sterne, Richard Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Theodoros Stamos, Jimmy Ernst, Barnett Newman, James Brooks and Mark Rothko. (DK307/DSphoto22)

The photo and article on the "Irascibles" was published in the January 15, 1951 issue of Life.

November 28 - December 16, 1950: Jackson Pollock's fourth solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (PP325)

32 paintings were shown, hung from floor to ceiling. (JP214) Works included Lavender Mist: Number 1; Number 3; Number 7; Number 8; Number 27; Number 28; Number 29; Autumn Rhythm: Number 30; One: Number 31 and Number 32. (PP325)

Jackson's brother Jay, a printer, attended the opening reception and wrote to his (and Jackson's) brother Frank "The big thing right now is Jack's show... [The opening was bigger than ever this year and many important people in the art world [were] present. Lee seemed very happy and greeted everyone with a smile, Jack appeared to be at home with himself and filled the part of a famous artist." (JP214)

Reviews in the general press were mixed - reviews in the art press were favorable. Robert Coates in The New Yorker (December 9, 1950) criticized One: Number 31 and Autumn Rhythm: Number 30 for their "meaningless embellishment." Howard Devree in The New York Times asked his readers "Does [Jackson Pollock's] personal comment ever come through to us?" Belle Krasne [B.K.] wrote in Art Digest (December 1, 1950) that the work was Pollock's "richest and most exciting to date" and Art News chose the exhibition as the second best solo show in their January 1951 issue. (John Marin was first and Alberto Giacometti was third). (JP215)

December 1, 1950: "Art and Honesty" at the Club with speaker David Hare.

Arguing that "subject matter covers a lack of imagination," he spoke against Surrealism which he considered to be mostly subject matter - in other words, not pure abstraction. (NE160)

December 8, 1950: Parker Tyler (editor of Art Digest) speaks against abstract art at the Club. (NE160)

December, 1950: Mark Rothko gets a job and a DeSoto. (RO273/287/613)

Rothko was hired as an assistant professor at Brooklyn College in the Department of Design with a starting date of February 1, 1951. He bought the DeSota from Milton Avery and his wife. (Rothko's wife, Mell, left her job at McFadden Publications around this time.) (RO273)

December 22, 1950: "Detachment and Involvement" at the Club with speaker Ad Reinhardt.

Philip Pavia described Reinhardt's talk as being about "a spiritual content for abstract art." (NE160)

December 28, 1950: Mark Rothko receives a financial statement from Betty Parsons.

Rothko sold six pictures during the year through the Betty Parsons Gallery as follows:

Number 11, 1950 was sold to Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III for $1,000. Number 9, 1950 was sold to Jeanne Reynal for $1,300. Number 10, 1950 was sold to Mrs. Joseph Branston for $500 (the work owned by MOMA with the same title was originally Number 10, 1951). Number 13, 1950 was sold to Walter Bareiss for $600. Number 22, 1950 was sold to Steve Burke for $900. Number 19, 1950 was sold to Heywood Cutting for $750. (RO273)

The sales totaled $5,050. After Parsons took out her 1/3 commission and a deduction of $86.97 for expenses, Rothko should have received $3,279.69. However, according to the statement, Rothko was sent a cheque for $1,313.02. It's possible that Parsons had advanced him some money earlier or paid him in installments. Two other works may also have been sold - Number 22, 1950 ($900) and Number 4A, 1950 ($600). (RO613n7)

December 30, 1950: Mark Rothko's daughter, Kate is born. (RO273)

Kathy Lynn Rothko (nicknamed "Kate") was conceived during Rothko's European trip earlier in the year. Rothko would proudly tell his friends, "We went to Europe two and came back three." (LM26) It was largely through Kate's diligence and persistence that the illegal dealings of Rothko's later gallery, the Marlborough, was exposed which led to the successful criminal prosecution of the head of Marlborough, Frank Lloyd. (See 1970-1974 and 1975-1979.)