Abstract Expressionism 1943

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

John Bernard Myers: "...I think Matta had been reading too much of the Marquis de Sade."

1943: Being and Nothingness by Jean Paul Sartre is published in France.

The first English translation (by Hazel Barnes) would be published in 1956.

1943: Katherine Dreier loans Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (or The Large Glass) to the Museum of Modern Art.

It was the first time the work had been exhibited since its 1926 debut in Brooklyn.

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

The Large Glass coincided perfectly with Matta's occult, erotic, and morphological interests... In response Matta embarked on a series of paintings that has sometimes been considered as a 'Duchampian suite'... Perhaps the culminating work in his dialogue with Duchamp is Vertige d'Eros of 1944, which alludes to erotic experience just as Duchamp does in the Large Glass... Among the various progeny spawned by the public appearance of the Large Glass or by Matta's interpretation of it, shown in his 1944 exhibition at Pierre Matisse, are two 1944 paintings by Rothko, Gyrations on Four Planes and Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea. The first is particularly a departure for Rothko in its apparently mechanical imagery and the experiment with multidimensional space. The second has been regarded as marking his own betrothal, since he had recently married for the second time. Rothko evidently told William Rubin that the second of these works was definitely inspired by the Duchamp and Matta works on the theme of betrothal. (SS322)

1943: André Breton excommunicates Kurt Seligmann and André Masson.

Breton expelled Seligmann from the Surrealist movement after a disagreement over the interpretation of a Tarot card. He expelled Masson over the inclusion of the French flag in a curtain design. The curtain was used for a performance to benefit the Free French movement and Breton thought that including the flag in the design was tantamount to nationalism. Both Seligmann and Masson had also done covers for the American Surrealist magazine, View, at a time when Breton was publishing his own Surrealist journal, VVV. (SS290)

1943: Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton split up.

Lamba moved into her own apartment on Bleecker Street. She would marry David Hare the following year (1944) after his divorce from Susanna Wilson. (SS290)

1943: Robert Motherwell's father dies.

1943: Philip Guston and wife have a daughter.

Guston's daughter Musa would later write (as Musa Mayer) Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston and various books relating to her struggle with breast cancer including Advanced Breast Cancer: A Guide to Living with Metastatic Diseases. Shortly after her birth Guston's wife stopped painting. (MM33/41)

1943: Mark Rothko meets Sidney Janis.

Sidney Janis was visiting artists' studios for his book Abstract and Surrealist Art in America. He asked Rothko whether he wanted to be in the Surrealist or abstract section and, according to Janis, Rothko answered "Oh, by all means the Surrealist." Janis was "struck by Rothko's confidence in himself" and, also recalls that Rothko "liked Miro very much." In around 1949, Janis hung a large Miro monochrome painting on his office wall and he later recalled that Rothko "used to come in specifically to look at that Miro." (RO334-35)

1943: Robert Motherwell makes his first collages.

1943: Barnett Newman meets Betty Parsons.

Barnett Newman met Betty Parsons at the home of Adolph Gottlieb and his wife, Esther. At the time Parsons was still running a small gallery at the Wakefield Bookshop located at 64 East 55th Street. (MH)

c. Early 1943: Matta and his wife, Anne (Alpert), have dinner with the Gorkys.

Anne saw Gorky as a loner, later saying "He was not part of the Abstract Expressionists." She thought he was "a good person" but "could go from happy to morose in two seconds flat." She described Gorky's wife Agnes as "down-to-earth" and "tough." (BA341) Agnes thought Matta "was so interesting and funny and very nice. He could talk up his work and wrap those art critics like James Thrall Soby around his little finger" whereas Gorky "seemed so tongue-tied." The couples often visited each other - sometimes joined by Isamu Noguchi. Despite their friendship Matta had still not introduced Gorky to André Breton by this time. (BA341)

Anne (sometimes spelled Ann) and Agnes were both pregnant at the dinner but whereas Gorky looked forward to the birth of his child, Matta was angered by Ann's pregnancy and threatened to leave her. (BA340) After the birth of twins, Matta did leave her and began a relationship with the heiress, Patricia Kane. (BA372)

1943: Helena Rubinstein goes on a buying spree at the Bignou Gallery.

The group show included two works by de Kooning: Pink Landscape (c. 1938) and Elegy (1939). De Kooning later told Joop Sanders about the sale: "Bill said that Rubenstein was buying the store, so to speak. She had bought one Renoir for $35,000. Bill's painting was, I think, $600. She said, "What is that?" They said 'It's a promising American painter named de Kooning.' So she said '$600. Throw it in for $450.'" (DK209)

Georges Keller, the owner of the gallery was also Janice Biala's dealer who knew Bill through her brother Jack Tworkov. Biala introduced Keller to de Kooning and although he promised Bill a one man show, de Kooning never sent in enough work to make up a whole show. (DK179)

January 1, 1943: Lee Krasner is dismissed from the WPA.

The WPA was folding and in the process of dismissing its artists. (JP127)

January 5, 1943: "Exhibition by 31 Women" opens at Art of This Century.

The women who exhibited included Djuna Barnes (Portrait of Alice), Leonore Carrington, Buffie Johnson, Frida Kahlo, the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee (a self-portrait), Louise Nevelson, Meret Oppenheim, I. Rice Pereira, Kay Sage, Hedda Sterne, Dorothea Tanning and Sohp[ie Taeuber-Arp, Peggy Guggenheim's sister Hazel, Guggenheim's daughter Pegeen and Barbara Reis. (MD240)

January 17- February 27, 1943: "Four American Artists" at the Riverside Museum.

The exhibition was first exhibition of the American Modern Artists (AMA) and according to Melissa Ho's chronology of Barnett Newman, was a "protest against the Metropolitan Museum of Art for its exclusion of modernist art from its juried exhibitions." (MH) Newman wrote the foreword for the catalogue although he was not a member of the organization. (MH/SS305)

Mark Rothko and Adolf Gottlieb were included. Rothko exhibited Seascape, Seated Figure, Sculptor and Nude. (RO164)

From the introduction in the exhibition catalogue:

We have come together as American modern artists because we feel the need to present to the public a body of art that will adequately reflect the new America that is taking place today and the kind of America that will, it is hoped, become the cultural center of the world... Isolationist art still dominates the American scene. Regionalism still holds the reins of America's artistic future. It is high time we cleared the cultural atmosphere of America... For the crisis that is here hangs on our very walls. We who dedicated our lives to art - to modern art - to modern art in America, at a time when men found easy success crying, 'to hell with art, let's have pictures of the old oaken bucket' - we mean to make manifest by our work, in our studios and in our galleries the requirement for a culture in a new America. (SG68)

January 30, 1943: Jackson Pollock is dismissed from the WPA.

Jackson's mother, Stella, wrote to his brother Charles on February 10, 1943: "Well the WPA folded up. Lee was let out the first of the year - she is taking a drafting course gets $17.00 while learning. Jack is going to take a course of some sort. He has done several new paintings very nice since I was down in November. Hope he finds something to do." (JP127)

February 1943: Franz Kline and Elizabeth move to 150 West 4th Street .

During 1943 Kline would also begin renting a studio in a ground floor storefront at 41 Perry Street which he would keep until the spring or summer of 1944. Being interested in metalwork, he retrieved copper sheets from a scrap-metal heap at the corner of 6th Avenue and Greenwich. He thought about making jewelry and cut out a galloping horse from the copper. (FK177)

February 1943: Jackson Pollock gets a job at Creative Printmakers on 18th Street.

Pollock got the job through Joe Meert, a friend from the Art Students League. He worked nights as a "squeegee man" responsible for silkscreening designs on neckties, scarves, plates and lipstick tubes. He lasted about two months (due to his drinking and meager productivity) in the job but continued to use the silkscreen process in some of his works. Screenprints that he produced c. 1943-44 are in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. (JP128)

[Note: The Jackson Pollock chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock places this in late 1942. (PP320)]

February 10 - March 21, 1943: "Americans 1943: Realists and Magic-Realists" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition included work by Clarence H Carter, Peter Blume, Philip Evergood, O. Louis Guglielmi, Paul Cadmus, Jared French, Charles Rain and Andrew Wyeth.

The Cultural Committee (headed by Adolph Gottlieb) of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors denounced the exhibition in the March 20, 1943 copy of The Nation. (RO158)

February 13 - February 27, 1943: "New York Artist - Painters" exhibition.

Included some of Rothko's 'myth' pictures - A Last Supper, The Eagle and the Hare, Iphigenia and the Sea and The Omen of the Eagle. Text in catalogue by Barnett Newman. (RO165)

Members of the New York Artist - Painters group included George Constant, Morris Davidson, John Graham, Louis Harris, George L.K. Morris, Mark Rothko, Louis Schanker, Vaclav Vytlacil and Adolph Gottlieb. (AG42)

February 17 - March 9, 1943: Franz Kline wins a prize at the 117th Annual Exhibition of the National Academy of Design.

Franz Kline won the $300 S. J. Wallace Truman Prize for Palmerton, Pa. and also exhibited a self-portrait at the show. Winners of the competition's highest prizes - two Altman prizes each worth $500 - were Antonio Martino, N.A. [National Academy] for Tower Street and Paul Clemens for Rainy Day.

Edward Alden Jewell, noted in The New York Times article covering the exhibition that "Hobart Nichols, president, announces in the catalogue that despite the fact that many members 'have put aside their profession for the duration' and are serving either in the armed forces or in defense jobs, the National Academy 'is determined to carry on its historic tradition and help continue, through this trying period, the cultural integrity for which we are all fighting.'"

(Edward Alden Jewell, "Landscape Takes $500 Altman Prize; Antonio Martino's Painting, 'Tower Street,' a Winner in National Academy Show," The New York Times, February 16, 1943, p. 13/FK177)

Franz Kline [from a letter c. February 1943 to his family]:

Now for some real news that came to me as a complete surprise. First I entered two canvases for the annual National Academy art show which you know I exhibited in last spring. Well, they usually take only one picture; that's the rule. This year to my surprise they accepted and are exhibiting the two. And for one of them I have received a $300 prize.. The winning picture was was a large painting from memory of Palmerton, Pa., the Lehigh Valley - yard train, station, and the hills leading home to Lehighton. The composition is slightly abstract and the mood of the painting seems to receive many compliments... (FK56)

In the February 21, 1943 issue of The New York Times, Edward Alden Jewell wrote "Of the several landscapes thus honored, those by Henry Gasser and Franz Kline are perhaps the most pleasurable." Other artists exhibiting in the show who merited a mention by Jewell in his article included Lillian Westcott Hale, Dorothea Chace, William Meyerowitz, William S. Schwartz, Sante Graziani, Maurice Sievan, Abraham Harriton, Tekla Hoffman, Annette Wolff, August Mosca, Elise Ford, Dorothy Andrew, Kenneth Washburn, George Schwasco, Kenneth Bates, Arthur Silz, Albert B. Serwazi, Dorothy Van Loan, Frances Greenman, Ivan Le Lorrain Albright, Ogden M. Pleissner, Robert Brackman, Louise E. Marianetti, Paul Sample, John F. Folinsbee, Louis de Valentin, Ivan G. Olinksy, Tosca Olinsky, Helen Sawyer, Mo Com, Frank London, Dines Carlsen, Marion Sanford, Ture Bengtz, Gene Alden Walker, Leon Kroll, Charles Hopkinson, Greta Matson, Paul Clemens, Mary Rand Birch, Gleb Derujinsky. (Edward Alden Jewell, "National Academy Annual; The 117th Yearly Round-Up Proves to Be Quite Characteristic As an Exhibition - A New Group - Dove, Gatch and Fiene," The New York Times, February 21, 1943, p. x11)

February 1943: Fernand Léger arrives in New York.

Léger arrived in New York in February 1943. (BA338) Arshile Gorky held a dinner for Léger and David and Mary Burliuk at his studio. Mary Burliuk noticed that the studio had been turned into comfortable sitting room and that when Léger arrived, Gorky appeared "thin, nervous, with his soft voice and enchanting laughter - looked overwhelmed with emotion." (BA338) Gorky's wife, Agnes spoke French fluently and served as a translator for the two artists.

Mary Burliuk:

The food served and eaten. It is late now. Léger is on the giant sofa. He speaks. He speaks French only. In five years in the States he did not learn one English sentence.

"I always have an interpreter," he explains. "A study of a new language would take me away from my art. I am a Frenchman, and that is good enough for me. Now if you are not in the mood to show me your paintings - don't do it. One's heart belongs to his art and not always one can open his heart. But I would like for Agness [sic] to tell me everything about Arshile's childhood. I want to know what made him feel that he must paint."

I felt sorry for poor Arshile. I felt sorry to see him so confused, shaken, almost crushed by the presence of Fernand Léger in his studio. Agnes began to translate her husband's quiet, deep moving words. (HH403)

Gorky told a favourite story from his childhood:

Arshile Gorky:

I remember myself when I was five years old. The year I first began to speak. Mother and I are going to church. We are there. For a while she left me standing before a painting. It was a painting of infernal regions. There were angels on the painting. White angels. And black angels. All the black angels were going to Hades. I looked at myself. I am black, too. It means there is no Heaven for me. A child's heart could not accept it. And I decided there and then to prove to the world that a black angel can be good, too, must be good and wants to give his inner goodness to the whole world, black and white world...

After that I remember faces. They are all green. And in my country in the mountains of the Caucasus is a famine. I see gigantic stones and snow on the mountain peaks. And there is a murmur of a brook below, and a voice sings. And this is the song. (HH403-4)

Gorky then started singing a song from his childhood.

February 1943: Klaus Mann attacks Surrealism in the American Mercury.

In his article Mann likened the Surrealists to the Nazis. (Mann became an American citizen the same year and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He committed suicide in 1949. (SS293))

Klaus Mann:

What I am trying to point out is the subtle and profound affinity between the murderous destruction of the Nazis and the playful destructiveness - of values, forms, sentiments, deep-rooted affections - of certain artistic movements, of which Surrealism is the latest and most spectacular exemplification... I am against Surrealism because I have seen what the world looks like with every esthetic and moral preoccupation being absent. It looks like hell or like a Surrealist painting. (SS292/Klaus Mann, "Surrealist Circus," American Mercury 56 (February 1943), 174-181)

Excerpts from Mann's article were published in the May 15th issue of Art Digest in an article by Peyton Boswell. Boswell referred to the "Dali-Breton-Ernst crowd" as "clever businessmen who know all the local stops of the publicity racket" but concluded that "The Surrealists are stimulating Americans to use their eyes less and their minds more, to develop their imagination." (SS293/Peyton Boswell, commentary on Klaus Mann's "Surrealist Circus," Art Digest 17 (May 15, 1943), p. 27)

[Note: Although Martica Sawin refers to Mann's article as the April issue of Art Digest in the main text of her book, Surrealism in Exile, the footnote indicates that the article was published in the February issue. (SS434fn4)]

March 1943: Max Ernst leaves Peggy Guggenheim.

Max left her for the young American Surrealist artist, Dorothea Tanning. Guggenheim also fell out with André Breton. He had promised her free advertising in his journal VVV for a show of VVV covers at her Art of This Century Gallery and he reneged on the deal causing her to cancel the show. Howard Putzel, a former art dealer from California became her new advisor. (DK203/SS291)

March 1943: Matta (and Gypsy Rose Lee) contribute to a double issue of André Breton's VVV magazine.

Matta contributed a series of drawings to accompany the poem 'Le jour est un attentat' by George Duits. Other artists who contributed work to the issue included the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, Kay Sage, Kamrowski, Lam and David Hare. (SS306)

March 1, 1943: Commercial illustration by Willem de Kooning in Life magazine.

Life magazine, March 1, 1943, p. 59

According to Stevens and Swan, Willem de Kooning did this illustration for an ad in Life magazine although they incorrectly attribute it to a "March 1942" issue in their biography of the artist.

March 13 - April 10, 1943: "Early and Late" exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery.

Peggy had planned an exhibition to showcase André Breton's magazine VVV, but after arguments with David Hare (the designated editor of Breton's journal) she decided instead to mount an exhibition of early and recent work by mostly Surrealist artists, including three works by Salvador Dali. (MD243)

March 15, 1943: The Norlyst Gallery opens. (SS295)

Jimmy Ernst's girlfriend, Elenore Lust started the gallery located at 59 West 56th Street. It would close in 1949.

Solo shows at the gallery during its first few months included Jimmy Ernst (c. early April 1943), Louise Nevelson (mid-April 1943) and Russian-born Boris Margo (May 1943).

The press release for the Ernst show (written by Ernst) seemed to distance the artist from Surrealism:

He believes that a painter can rely on certain principles of Surrealism without identifying himself with the movement.... He attempts to translate into art forms the scientific inquiries of this generation. This is the presentation of the effect of this new scientific age upon a young artist. (SS304)

The gallery was run informally and artists were welcome to stop by - visitors included Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb would often visit. (SS296) When Rothko's wife left him later in the year he moved in with Boris Margo.

Rothko would move in with Boris Margo later in the year after he (Rothko) split up with his wife. (See autumn 1943.)

March 20, 1943: David Burliuk introduces Arshile Gorky to Joseph Hirshhorn. (BA342)

Burliuk brought art collector Joseph H. Hirshhorn to Gorky's studio. Hirshhorn initially bought sixteen Gorkys (now in the Hirshhorn Museum) and later purchased thirteen more. He later said about Gorky, "He looked like a great big Turk. I loved him." (HH404)

Agnes ["Mougouch"] Gorky:

He [Hirshhorn]: made nouveau-riche remarks, and he chose very nice things. He liked the little paintings with people in them, not the abstract ones. For about six hundred dollars he got a large pile of Gorky's little paintings on shirt cardboards - the ones Gorky called 'valentines' - and gave them away when people came to dinner. Gorky did not show Hirshhorn his larger paintings. (HH404)

According to Gorky's wife, Hirshhorn bought "30 Gorkys for about $300 or so. Small ones. A bargain basement." (BA342)

Spring 1943: Max Ernst leaves Peggy Guggenheim.

Ernst left Guggenheim after about a year of marriage to live with Dorothea Tanning who he had met at Julien Levy's gallery in the summer of 1942. (SS291)

Spring 1943: New Frontiers in American Painting by Samuel Kootz is published.

Although published in 1943, according to Kootz the book "was completed I think in 1941." (KD)

Sam Kootz [from the foreword]:

So ardent has been the attack upon the American public by our flossier refugees (Ernst, Tanguy, Dali, Matta, et al.), so well regarded are they in the high places of our museums and galleries, that our American spectators may very well make the mistake that this is an important development in contemporary painting.... Surrealism may be the current music hall favorite, but I am convinced that its unwholesome show will have only a short run on the boards. (SS295/Samuel Kootz, New Frontiers in American Painting (NY:Hastings House, 1943)

April 5, 1943: Arshile Gorky's daughter, Maro, is born.

Agnes' waters broke while she, Gorky and her mother were at the cinema. Maro was born at 8:30 am. Gorky named her Maro after a legendary heroine of his childhood with the same name (based on Mariam Vardanian, one of the founders of a revolutionary party working for a unified socialist Armenia.) His nickname for his new daughter was "skybaby." A friend of Gorky, Jane Gunther, noted that Gorky "looked like a child himself, as he watched the baby, entranced." (BA343)

While Agnes recuperated in the hospital, Gorky fixed up the studio for her return. He cleaned it, tried (unsuccessfully) to build a cradle, hung up "welcome home" signs and put out flowers. Agnes' mother paid for an English nurse to help look after the baby for a short period after it was born. The nurse, "Miss Wilkes," had previously worked for General Pershing. She arranged for a postnatal check-up with one of the most famous doctors in New York, Dr. Bartlett. Bartlett had been Dr. Spock's teacher, was the author of the Bartlett Baby Book, and had coined the expression, "Cow's milk is meant for calves and mother's milk is meant for babies." When Agnes discovered that Miss Wilkes had made the appointment she rang up Barlett's office to cancel it, saying it would be too expensive. Bartlett's secretary told her not to worry about that.

Dr. Bartlett visited the Gorkys in their studio and after seeing the paintings on the wall, exclaimed "Picasso! Pissarro!" and gave a deep bow to Arshile. After blowing a large cloud of cigar smoke in the new baby's face he pronounced her lungs "excellent" and "healthy" and told Agnes to bring her to see him in his office in a week. Both Gorky and Agnes thought he was wonderful. When Agnes visited him in his office he would bring out a bottle of champagne. They never received a bill for his services. (BA343-44)

April 5, 1943: Matta, Drawings exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA308)

It was the first exhibition by Levy at his new gallery at 42 East 57th Street. The gallery had previously been located at 602 Madison Avenue (1931 - spring 1937), then at 15 East 57th Street (autumn 1937 - spring 1941), then at the Durlacher Bros. at 11 East 57th Street (early 1942 - early 1943).

April 1943: Peggy Guggenheim scouts young talent.

Guggenheim placed an ad in the April 1943 issue of Art Digest for a juried "Spring Salon for Young Artists" to take place at her Art of This Century Gallery. Any American artist under the age of thirty-five could submit samples of their work. The finalists would be chosen by a jury consisting of Peggy Guggenheim, Piet Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, James Joseph Sweeney and James Thrall Soby. (DK204-5/MD245)

One of the artists to be considered was Jackson Pollock. Peggy's secretary/advisor, Howard Putzel, was an early champion of Pollock, referring to him as a "genius" and Matta had also recommended Pollock. But Peggy couldn't really see it. Putzel, urging Peggy to consider Pollock for the Spring Salon went round to Jackson's 8th Street studio and brought a selection of his work to the Art of This Century for consideration by the jury. While Mondrian was examining Pollock's Stenographic Figure (1942), Peggy commented, "Pretty awful, isn't it? That's not painting, is it?" After Mondrian had been in front of the work for several minutes, she continued her critique: "There is absolutely no discipline at all," adding that she didn't think Pollock would be chosen for the show. Mondrian replied, "Peggy, I don't know. I have the feeling that this may be the most exciting painting that I have seen in a long, long time, here or in Europe." (MD245-6)

Among the artists that Guggenheim would give one man shows to during 1943 - 1945 were William Baziotes, Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. (AG42)

April 16 - May 15, 1943: Jackson Pollock exhibits Collage at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century.

The work was included in a group show of collages by international artists. (PP320) On the advice of Matta, Peggy had asked Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell if they would be willing to submit some collages, although neither had done collages before. Motherwell suggested they work together. They worked in Jackson's studio with Motherwell enjoying the collage medium (which he would continue to do) and Pollock unsatisfied with his results. The collage he did which was exhibited at the gallery but didn't sell and Jackson threw it away after the show closed. On the exhibition announcement his last name was misspelled as "Pollach." (JP132)

Other artists in the show included Joseph Cornell, Ad Reinhardt, David Hare, Jimmy Ernst, Alexander Calder, Laurence Vail and Gypsy Rose Lee. (MD244)

[Note: According to Mary Dearborn in Mistress of Modernism: The Life of Peggy Guggenheim the "Collages" exhibition took place from April 4 - May 15, 1943.]

May 5 - May 25, 1943: Max Ernst, Drawings exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA308)

May 8, 1943: Jackson Pollock starts work at The Museum of Non-Objective Painting at 24 East 54th Street.

In 1952 the museum would be renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. (PP320) The museum's director, the Baroness Hilla Rebay was hiring young artists to work at the museum giving them a monthly salary and free art supplies. Pollock did various jobs during his employment - running the elevator, counting the visitors, helping to make frames. A fellow worker, Leland Bell, recalled Pollock's bravado - "I could do an Arp easy!" or "Klee? I could do a Klee easy." (JP128-9)

The Baroness required that the young artists she hired bring their work in on a monthly basis so she could criticize it. When she saw one sketch by Pollock, she ripped it in half. "This - NO!" she proclaimed in her German accent. (JP129)

Pollock resigned from the job after Peggy Guggenheim offered him a contract. His letter of resignation to Baroness Hilla Rebay was dated July 21, 1943. (JP135)

May 18 - June 26, 1943: "This Century's Spring Salon of Younger Artists" at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of the Century Gallery.

Jurors for the exhibition were Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian, James Johnson Sweeney, James Thrall Soby, Peggy Guggenheim and Howard Putzel.

Philip Pavia later said of the show, "That show was the first melting pot of Surrealism and of abstraction... It was a big transitional show. I think this was really the birth of New York as an art center, even with all those foreigners around." Included in the exhibition was Jackson Pollock's Stenographic Figure (1942) which was originally called Painting. The show also included work by Robert Motherwell and Matta. (DK204)

Although there were more than 30 painters in the show, Jackson was singled out in the press. Jean Connolly wrote in The Nation that Jackson's painting left the jury "starry-eyed." Robert Coates wrote in The New Yorker that, although most of the work was amateurish, "in Jackson Pollock's abstract Painting, with its curious reminiscences of both Matisse and Miró, we have a real discovery." (JP133)

c. Late May/early June 1943: Arshile Gorky, Agnes and their daughter Maro travel to the Magruders' Virginia farm. (BA345/HH413)

The Magruders, Agnes' parents, owned Crooked Run Farm in Virginia. The Gorkys initially stayed with a neighbour while repairs to the farm were being carried out. Arshile cleaned up a disused barn and used it as his studio. One of the locals, Mr. A.M. Janney recalled Gorky coming into the chandler's shop to collect his mail.

A.M. Janney:

He'd just come here in his overall with a high bib. That's all. No shirt and always barefoot with a long staff. Didn't look like the rest of the or'nary folk going up and down the road with pants and a shirt on. He looked like a European peasant, a rough farm boy. I was born in 1908. He looked ten years older than me. He'd been all over the world; I'd never been out of Lincoln. I tried to get to talk to him once in a while, but he was hard to unnerstand. Never worried about learnin', stand around and talk, best he could. I guess he was different from other people. He was quaar! (BA346)

Near to the farm lived Bob and Mary Taylor who were Quakers and dairy farmers. Bob later recalled that the Gorkys were still staying on the farm in October 1943 when Mary gave birth to her her second child.

Bob Taylor:

His [Gorky's] behaviour wasn't particularly odd, but people said so. Always on the byways up and down, in short pants and huge bare feet, he was dreaming or finding things to paint. I don't ever remember seeing him with an easel and brush. Never. He looked as though he didn't have anything at all on his mind. We liked him very much. He was such a nice man, interesting, funny, told jokes. (BA346)

The Taylors also recalled that "Agnes was an enthusiastic Communist at this time. She quoted her father saying, 'The FBI have a file this big on my daughter.'" (BA347) Mary Taylor had taken an art history course and visited the Mellon Gallery with Gorky who surprised her by saying that some of the Rembrandts weren't genuine. (He was later proved right.) (BA347)

Gorky drew a large amount of drawings while at the farm inspired by the natural surroundings. According to one of his biographers Nouritza Matossian, "he also began using crayons in a totally new fashion. He drew bold outlines with pen and ink, then used colours to create different forms, out of synch with the black outlines, often leaving much of the background bare, in parallel with his recent innovations in painting... He used a mixed range of media; many works were done in pencil and crayon, pen and ink with pastel, crayon and wax. He varied the ways of applying crayon marks for texture and grain. He was delighted when the wax crayons melted in the sun, a luscious medium forming a veneer." (BA348) According to Agnes, he told her that he "saw the trees as battles and horses in Uccello, and he saw knights in armour and everything alive, their arrangement against the sky or against the hillside. He saw everything in tensions and relations of shapes to each other." (BA349) Gorky repeatedly asked her opinion as to whether the drawings held something new. When, after returning to New York he showed the Virginia drawings to Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art, she thought they were a breakthrough and told him she was "crazy about them." He offered one as a gift but she had to refuse because as a MOMA employee she could not accept a gift from an artist. But she did borrow three of them for a traveling exhibition. (BA351)

The Gorkys returned to New York in October 1943. (MS261)

Spring 1943: Willem de Kooning moves again.

This time de Kooning (and Elaine) moved into the loft above his at 156 West Twenty-second Street. Willem and Elaine had decided to get married and de Kooning planned to overhaul the new space, telling Marjorie Luyckx, "I'll build her (Elaine) the most beautiful house in the world." (DK193)

Summer 1943 or 1944: Barnett Newman and wife visit Peabody museums.

Barnett and Annalee visited the Peabody museums in Salem and Cambridge, Massachusetts to see the African, Northwest Coast Indian and Pre-Columbian collections. (MH)

Summer 1943: Robert Motherwell spends his second summer in Provincetown.

Summer 1943: Franz Kline serves as second lieutenant in the reserve corps at the Citizens' Military Training Camp, Fort Monroe. (FK177)

c. Summer 1943: Franz Kline meets Willem de Kooning at Conrad Marca-Relli's studio at 148 West Fourth Street. (FK177)

June 1943: Mark Rothko and his wife Edith separate permanently. (RO170)

In divorce papers filed later in the year, Edith indicated that she and Rothko had separated in June. (RO203) It was their second separation. Their first was in 1940. They got back together after the first separation but continued to argue - often about money. Edith had an increasingly successful jewelry business and Rothko's paintings weren't selling.

Rothko was hurt by the separation (and later divorce) - although he would also later complain to Milton Avery's wife that marriage to Edith had been "like living with a refrigerator." (RO205) Howard Baumbach recalled that Rothko had a "serious breakdown" around the time of his separation/divorce and had checked into a hospital where Baumbach and Adolph Gottlieb visited him. (RO204)

After the separation, Rothko stayed temporarily with Jack Kufeld, one of the original members of The Ten, in a hotel apartment on West 74th Street before leaving New York and going back to visit his family in Portland. (RO204) Although Rothko biographer, James E.B. Breslin, indicated they separated in June in Mark Rothko: A Biography, Kufeld recalled that the separation occurred at the end of the summer.

Jack Kufeld:

... at the end of one summer, and I don't know which one it was, Edith and Mark decided to call it quits. I had taken an apartment in a little hotel on 74th Street next to the Berkeley. It's now converted into some kind of a mission society. It was a small hotel, very pleasant. Mark moved in with me. He was very unhappy and very disturbed. In a previous time we used to spend the night talking about art and what his aims were, and we sort of continued in that vein. And, as far as he was concerned, it was always the same thing - that he was looking for the essence of the essential. That was his whole aim. (JK)

Summer 1943: Mark Rothko meets Clyfford Still.

After visiting his family in Portland, Mark Rothko traveled to the Bay area where, in Berkeley, he met the painter Clyfford Still at the home of musicologist Earle Blew. (RO205/221) Rothko and Still didn't discuss painting at the time. It wasn't until Still moved to New York that Rothko saw his work - about two years after their initial meeting.

Summer 1943: Mark Rothko meets Buffie Johnson.

After visiting the Bay Area, Rothko continued to Los Angeles where he visited his cousin Arthur Cage and Louis Kaufman (the Portlander who had introduced Rothko to Milton Avery). (RO205) Gage was married to a Hollywood drama coach named Sophie Rosenstein. One of her students was the actress Ruth Ford, the sister of Charles Henri Ford (the editor of View magazine). Buffie Johnson was visiting Ruth that summer so Sophie rang her and asked if she could bring her nephew, Mark Rothko, for a visit. (RO207) When Rothko showed Buffie some watercolours he had done in a small spiral notebook, she was impressed by the Surrealist images, saying "The only place I feel these really belong is Peggy Guggenheim's gallery." Buffie had known Guggenheim in Paris. When Rothko returned to New York (after Buffie had also returned there), she introduced him to Peggy Guggenheim's advisor, Howard Putzel. (RO208)

June 1, 1943: Franz Kline is included in the inaugural exhibition of the Village Art Center.

Only artists from Greenwich Village were eligible to exhibit.

Edward Alden Jewell:

Much of the work now displayed may be called, shall we say, villagy, Washington Square outdoorish, Society of Independesque. Some of the paintings... are far more accomplished - those for instance, by Fred Buchholz, William Fisher, Franz Kline and Ragnar Olson. (Edward Alden Jewell, "End-of-the-Season Melange," The New York Times, June 6, 1943)

June 2 - 26, 1943: Third exhibition by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors takes place at the Wildenstein Gallery.

A battle ensued in the pages of The New York Times between their reviewer, Edward Alden Jewell and the Federation represented by two of its founders Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko (with the help of Barnett Newman).

See Edward Alden Jewell vs. The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors.

June 22, 1943: Matta's wife, Anne, gives birth to twins.

John Bernard Myers [diary entry March 1946]:

... Matta is high-strung, hyperactive, given to playing cruel jokes (l'humour noir), a womanizer. Although he is married to a lovely, quiet girl named Anne, he does not adhere to the Surrealist ideal of monogamy. The incident that has caused the most gossip is the fact (and it is true) that when he heard his wife had given birth to identical male twins, Matta instantly developed two black eyes and looked as if he had been socked in a boxing match. He was so 'struck' by this experience that he packed his bag and abandoned the family. Edouard Roditi says it is the first case of an authentic stigmata since the blessed Saint Teresa of Lisieux ("a bourgeois saint, my dear") received hers. I said I think Matta had been reading too much of the Marquis de Sade. (JB67)

Four months after their births, Matta left his wife and only saw his sons sporadically. Initially Matta moved from his and Anne's small apartment on Patchin Place to live in the apartment of Isabelle Waldberg whose husband was overseas working for the Office of War Information. He would later marry Patricia Kane who would leave him after several years for Pierre Matisse. Matisse divorced his American wife Teeny in 1953 who would later marry Duchamp. (SS291)

Both of Matta's sons died early deaths. John Sebastian fell from the window of his brothers studio in 1976 after being in and out of mental hospitals. His brother, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, died of pancreatic cancer two years later.

June 26, 1943: Peggy Guggenheim visits Jackson Pollock in his studio.

In the morning of the day that Guggeheim had arranged to visit Pollock's studio, Jackson attended Peter Busa's wedding. He was supposed to be the best man but got so drunk before the ceremony that he fell asleep on the living room floor. He was put in a bedroom until after the ceremony when Lee Krasner woke him up to remind him that Peggy Guggenheim was visiting his studio that day. She took him for a coffee to sober him up and as they were approaching their building they saw Guggenheim coming out of it, furious because nobody was at home. (JP134/PP320)

From Jackson Pollock: A Biography by Deborah Solomon:

Pollock and Lee were nearing their building when they spotted Peggy Guggenheim coming out. She was furious. Where had Pollock been? How dare he waste her time! When Peggy Guggenheim accompanied Pollock and Lee back upstairs, she became even angrier. The first thing she saw in the living room were paintings signed "L.K.' [Lee Krasner]" She started to shriek. "L.K.! Who's L.K.? I didn't come to see L.K.'s work." It was the beginning of a long animosity between the two women. As Lee once said, never again could she look at Peggy Guggenheim without thinking, "What a bitch."

Guggenheim signed Pollock to her gallery in July (see below).

[Note: The MoMA Jackson Pollock chronology in Jackson Pollock indicates that Guggenheim's visit took place on the 23rd. Deborah Solomon's biography of Jackson Pollock indicates that it took place on a Saturday - the same day as Peter Busa's wedding which was the 26th. According to the MoMA chronology Guggenheim delayed her decision about offering Jackson a show until Duchamp visited his studio. (PP320)]

June 30, 1943: The Federal Art Project of the WPA is disbanded.

July 1943: Peggy Guggenheim offers Jackson Pollock a solo show, a contract and a mural commission.

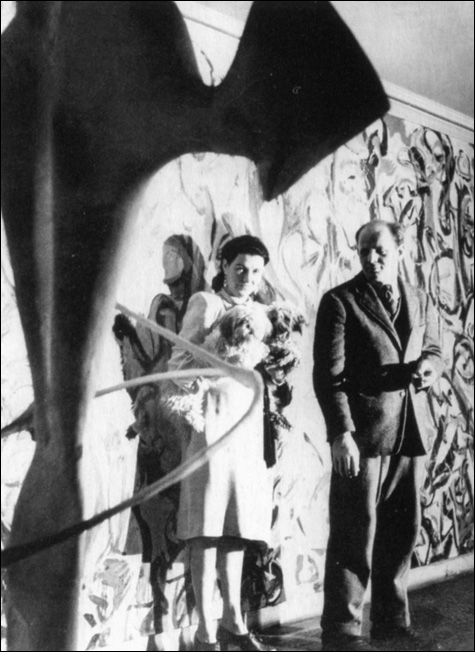

Jackson Pollock and Peggy Guggenheim in front of the mural she commissioned for her New York town house, 1943

(Photo: Mirko Lion) (KV320)

The solo show was planned for November 9, 1943. The contract was for one year giving Pollock $150 month and a year-end settlement if he sold more than $2700 worth of paintings. If he didn't sell that amount Guggenheim would receive paintings to make up the difference. (JP135) His letter of resignation to Baroness Hilla Rebay was dated July 21, 1943. (JP135)

Guggenheim also commissioned him to do a mural for the entrance hallway of her town house at East 61st Street. Although she initially wanted Pollock to paint directly on the wall, Duchamp convinced her that it would be better done on a canvas which she could take with her if she moved. (PP320)

On July 29, 1943 Pollock wrote to his brother Charles, "I have it stretched now" referring to the canvas for the large mural - "It looks pretty big, but exciting as hell." (JP137)

During this period, Pollock also worked on some smaller works including four untitled abstractions in which he experimented with paint-dripping as a technique. (JP139)

Autumn 1943: Mark Rothko returns to New York.

In early October, Milton Avery wrote to Kaufman, "Marcus reported very extensively about his visit to you. Did he say anything about his break up with Edith?... She has a divorce and he has taken a place on 52nd." (RO205) The 52nd Street address that Avery referred to was an apartment that Rothko shared with the painter Boris Margo in a hotel at 22 West 52nd Street. According to Rothko's sister Sonia when Edith visited him at Margo's place she "looked around and said, 'This is the kind of thing I took you out of" - a comment his sister recalled "hurt him deeply." Rothko wrote to his sister ... "here at the age of 40 I am on the brink of a new life. It is both exciting and sad, but I regret nothing about it. The last thing in the world I would wish would be to return to the old one." (RO205)

Autumn 1943: Clement Greenberg meets Mark Rothko.

Clement Greenberg and a friend had a drink with Rothko at the Murray Hill Hotel. (RO383)

Clement Greenberg:

We talked and I found Rothko sympathetic, but I also found him very square. Later on he got pompous. He always stayed a little square. (RO383)

October 1943: The Gorkys return to New York from Virginia. (MS261)

November 9 - 27, 1943: Jackson Pollock's first solo exhibition takes place at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery.

Lee Krasner helped with the hanging of the exhibition and also with the folding and addressing of the four page catalogue for the show. When Guggenheim saw that Lee had wrongly addressed some already stamped envelopes she yelled at her for wasting the postage. Pollock, himself, had little to do with the actual installation of the show. Peggy Guggenheim's assistant, Howard Putzel became a frequent visitor to Pollock's studio at 46 East Eighth Street, often complaining about working for Guggenheim: "I don't know how I can face another day." When James Thrall Soby, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, stopped by Art of This Century and saw some of Pollock's works prior to the exhibit, Putzel wrote to Pollock, "Soby dropped in the afternoon and is mad about your work," adding that Soby "predicts you'll be THE new sensation of the season, and moreover, that, unlike past season's sensations, you'll last." (JP139-140)

The exhibition was the first solo show by an American artist at the gallery. It consisted of fifteen oil paintings and numerous works on paper, all executed between 1941 - 1943. The paintings were Guardians of the Secret, The Mad Moon-Woman, The Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle, The She-Wolf, Stenographic Figure and six untitled works. Prices ranged from $25 to $750. By the time the exhibit closed no paintings had been sold, although Alfred Barr from The Museum of Modern Art would purchase The She-Wolf between the closing of the exhibition and the opening of Jackson's second solo show at the gallery, about a month after a large color reproduction of the work appeared in the April 1944 issue of Harper's Bazaar as part of an article "Five American Painters" by James Johnson Sweeney . (JP142)

When Sidney Janis, who was writing his book Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, asked Jackson to contribute a statement about The She-Wolf for his book, Pollock commented, "She-Wolf came into existence because I had to paint it. Any attempt on my part to say something about it, to attempt explanation of the inexplicable, could only destroy it." (JP138)

James Johnson Sweeney wrote the introduction for the 4 page exhibition catalogue of Jackson's first solo show:

James Johnson Sweeney [from the exhibition catalogue]:

Pollock's talent is volcanic. It has fire. It is unpredictable...It is lavish, explosive, untidy... What we need is more young men who paint from inner impulsion without an ear to what the critic or spectator may feel - painters who will risk spoiling a canvas to say something in their own way.

Sweeney also noted that "It is true that Pollock needs self-discipline." (JP140) Although Jackson sent a note of thanks to Sweeney on November 3rd, he was upset by his comment about the lack of self-discipline. He painted another work, Search for a Symbol, and took it to the gallery to show Sweeney before the paint had completely dried on the canvas, referring to the work as "a really disciplined painting." The painting was added to the show at the last minute and the Art Digest reviewer, Maude Riley, in her review of the exhibition in her "Fifty-seventh Street in Review" column that appeared in the November 15th issue, noted that the work was "wet with new birth." (JP141)

Robert Coates reviewed the show for The New Yorker: "At Art of This Century there is what seems to be an authentic discovery - the paintings of Jackson Pollock... the effect of his one noticeable influence, Picasso, is a healthy one, for it imposes a certain symmetry on his work without detracting from its basic force and vigor." (JP141)

Clement Greenberg wrote in The Nation (November 27, 1943) that "Jackson Pollock's one-man show establishes him, in my opinion, as the strongest painter of his generation and perhaps the greatest one to appear since Miró." (DK207) Greenberg noted that the smaller works in the show were "the strongest abstract paintings I have yet seen by an American" although he thought that with the larger paintings, Pollock, "being young and full of energy... takes orders he can't fill" and "spends himself in too many directions at once..." (JP142/3)

Milton Resnick later noted about about Jackson's success - "They had been waiting for the American glamour boy in art... Who were they going to go to - a Dutchman, an Italian, a Jew, a Greek? Where's the American? He filled the bill." (DK208)

October 13, 1943: Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko appear on WNYC radio.

Gottlieb and Rothko attempted to answer four questions during the radio statement - "The Portrait and the Modern Artist:"

1 Why do you consider these pictures to be portraits?

2 Why do you as modern artists use mythological characters?

3 Are not these pictures really abstract paintings with literary titles?

4 Are you not denying modern art when you put so much emphasis on subject matter?

In his answer to the fourth question, Gottlieb said, "It is true that modern art has severely limited subject matter in order to exploit the technical aspects of painting. This has been done with great brilliance by a number of painters, but it is generally felt today that this emphasis on the mechanics of picture making has been carried far enough. The Surrealists have asserted their belief in subject matter but to us it is not enough to illustrate dreams."

see WYNC transcript of "The Portrait and the Modern Artist"

November 17, 1943-February 6, 1944: "Romantic Painting in America" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition traced the history of romanticism in America and included artists such as Thomas Cole, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Marin, Jon Corbino, Darrel Austin, Henry Mattson, Morris Graves and Loren MacIver.

The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors criticized MOMA "for adopting one set of standards for the European art which it displays and a thoroughly different one for its American selections" which they thought emphasized "such ephemeral fads as the output of certain refugee-Surrealists and types of American scene-illustration." (RO159)

James T. Soby, the director of the museum at the time, reacted by writing to some of the Federation's members asking them if they supported the Federation's statement. Clement Greenberg in The Nation (February 12, 1944) wrote that the museum's tactic was reminiscent of "the Stalinist telephone-pressure campaigns of a few years ago" and that The Museum of Modern Art would end as "an educational annex to the Stork Club." (RO159)

December 1943: "What about Modern Art and Democracy" by Stuart Davis is published in Harper's magazine.

In his article Davis criticized "isolationist culture" and the American Scene painters.

Stuart Davis [from "What about Modern Art and Democracy"]

Isolationist culture is reactionary and undemocratic in character in that it seeks to suppress that free exchange of ideas which alone can develop an authentic modern American art... The American Scene philosophy parallels political isolationism in its desire to preserve the status quo of the American Way of Life. (SG77)

December 1943: The government auctions off WPA paintings.

The paintings were auctioned off at a Flushing warehouse along with other surplus property. Paintings were removed from their stretchers and sold by the pound. A plumber bought the entire lot of paintings hoping to use the canvas to insulate pipes but soon discovered that when the pipes got hot, the oil paint started to smell. So he sold the canvases to a junk dealer who then sold them to Roberts Book Company on Canal Street where they were stored on long tables in the back of the shop. Herbert Benevy, the owner of the Gramercy Art Frame Shop, was among the people who purchased some of the works for $3 a canvas. His selection included paintings by Milton Avery, Alice Neel, Joseph Solman, Mark Rothko and two paintings by Jackson Pollock. (JP81)

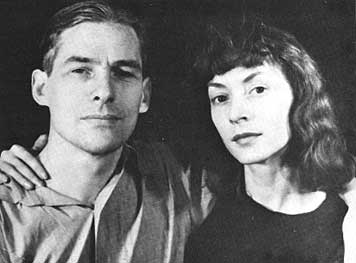

December 9, 1943: Willem de Kooning marries Elaine Fried.

Bill and Elaine de Kooning shortly after their marriage (1944)

(Photo: Ibram Lassaw (JG))

The wedding was a small ceremony in City Hall. Three of Elaine's siblings attended - Marjorie, Peter and Charlie Fried. Bart van der Schelling was the best man. Also in attendance were Alain Brustlein and his wife, Janice Biala. Elaine's brother Conrad failed to attend, later saying "I didn't think it was important. They were already living together." Elaine's mother also failed to attend, giving the excuse that Elaine (at the age of 25) was too young to marry. Janice Biala recalled that she and her husband ended up throwing a spontaneous informal wedding lunch at a cafeteria. After the lunch they said goodbye to the couple who then returned to their studio to continue to working. (DK197)

Elaine de Kooning:

Actually the wedding was kind of bleak. Afterwards, we went to a bar in the downtown district and we all had a drink. Oh, I guess it wasn't that bleak. It was kind of amusing. But it was not festive. I mean nobody rolled out the red carpet for us. (DK197)

Not long after the marriage, de Kooning discovered Elaine in bed with Robert Jonas.

From de Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

For Elaine, playing the field became a way not only to be admired by men, but to give as good as she got. Once, not long after her marriage and well before she began to have affairs openly, she became ill at a party at their Twenty-second Street loft after drinking too much. At some point, de Kooning went solicitously into their freestanding bedroom to check on her condition, only to find her in bed with her old flame Robert Jonas. Enraged, he pulled Elaine out of the bed and cuffed her around, blaming her and not his old friend. (DK240)