Abstract Expressionism 1961

by Gary Comenas

In 1961, John Graham dies in London England; Mark Rothko exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art; Mark Rothko visits Dr. Grokest - "According to Grokest, Rothko told him 'that he'd been living on alcohol for six weeks.'" (RO411); Franz Kline is admitted into hospital; Mark Rothko visits England; "American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Willem de Kooning punches Clement Greenberg; Claes Oldenburg opens "The Store"; Willem de Kooning has an affair with Marina Ospina.

* * *

1961: John Graham dies in London England.

Grace Glueck ["Gallery View; An Artist Finds New Favor," The New York Times, November 11, 1984]:

"The Russian-born artist John Graham (1881-1961) had so many strings to his bow that his gifts as a painter were somewhat underexercised. A brilliant if crotchety theorist and critic, he wrote an insightful treatise, System and Dialectics of Art (1937), that prefigured Abstract Expressionism. A keen promoter of talent, he was the first to recognize Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, and he influenced David Smith's decision to concentrate on sculpture. A connoisseur, collector and dealer, he helped to expand the interest in African and Oceanic art in this country. He was also a yoga practitioner, a linguist, an amateur anthropologist and a mystic. As a painter, he was far from prolific, but he understood thoroughly the language of Cubism, and he reaffirmed its validity for the younger generation of Gorky, de Kooning and Pollock at a time when American Regionalist painting had a powerful grip."

Roberta Smith ["A Charismatic Artist Who Was Known for Talk," The New York Times, December 2, 2005]:

"John Graham, born Ivan Gratianovich Dombrowski in 1886 in Kiev, was a man of many parts and even more words, who talked as much as painted his way into the history of 20th-century American art... Graham's artistic development began in earnest after he reached New York in 1920 - to the late 50's... Married four times, he has been characterized as a womanizer, but it seems more complicated than that, starting with the fact that he often stopped painting when he was in a relationship. His greatest love may have been Marianne Strate-Felber, Ileana Sonnabend's mother. They met in 1943 and lived in Strate-Felber's brownstone at 4 East 77th Street, in the apartment that eventually became the gallery of her son-in-law, Leo Castelli. When Strate-Felber died in 1955, Graham was desolate and embarked on a series of troubled, often obsessive relationships (and accusatory correspondences) with younger women, including Isabelle Colin du Fresne, the Frenchwoman who would become Andy Warhol's superstar Ultra Violet. He died in London in 1961."

1961: Robert Motherwell begins to make prints.

The prints were made at Tatyana Grosman's Universal Limited Art Editions Studio, West Islip, Long Island. (HM)

1961: Robert Motherwell retrospective at the VI Bienal de Arte, Sao Paolo, Brazil. (HM)

1961: Rothko sells eight paintings.

Rothko sold eight paintings during 1961 through his dealer Sidney Janis. Janis, himself, bought three of the paintings sold that year: Maroon on Blue ($8,000), Red and Orange ($5,333.34), and Yellow Stripe ($6,000). The other five paintings sold were Dark over Light (1954) ($9,000); Violet Bar (1957) ($8,000); Yellow Band (1956) ($12,000); Brown, Blue, Brown on Blue (1953) ($15,000); and Black and Dark Sienna on Purple (1960) ($15,000). (RO636-7n5)

[Note: Burton and Emily Tremaine purchased Maroon on Blue from Janis the same year that Janis purchased it from Rothko.

(RO640n30)

1961: Peggy Guggenheim sues Jackson Pollock's estate.

Guggenheim argued that Pollock had defrauded her by not following the terms of their 1946 contract which stipulated that Pollock would give her all his output bar one painting of his choosing. She sued Lee Krasner for $122,000. The suit dragged on for four years before Guggenheim finally dropped the charges and accepted two Pollock paintings in settlement. (JP157)

1961: Adolph Gottlieb is awarded third prize at the Pittsburgh International Exhibition, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, PA.

January 1961: Ben Heller buys Barnett Newman.

Newman sold Vir Heroicus Sublimis to Ben Heller in January. Other sales in 1961 were L'Errance to Robert and Ethel Scull and Onement VI to Frederick and Marcia Weisman. (MH)

January 18 - March 12, 1961: Mark Rothko exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

The Museum of Modern Art requested a 10 percent commission on any sales from the exhibition. In a letter to the director of the Museum of Modern Art, René d'Harnoncourt, Rothko's dealer, Sidney Janis, responded that none of the works on loan from the gallery were for sale and that should they become available for sale, "they will first be made available to those already on our waiting list." (RO413)

The show also traveled to the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (October 10 - November 12), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (November 24 - December 27), Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles (January 6 - 29, 1962), Kunsthalle Basel (March 3 - April 8), Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome (April 27 - May 20), and the Musee d'Arte Moderne de la Ville de Paris (December 5, 1962 - January 13, 1963). (RO411)

Dan Rice [Rothko's assistant]:

"He [Rothko] was the kind of personality that approached all public displays with great and horrendous turmoil, great anxiety... Before an opening, he would throw up, more like the behavior of an entertaining artist, an actor. He literally had to go to bed as an exhibition approached. He'd be physically ill. I don't mean come down with a cold or something like that. He'd be throwing up, just completely torn apart, physically as well as mentally." (RO373)

James Brooks, who had a studio in the same building (222 Bowery) as Rothko, recalled a conversation he had with Rothko during the time of the exhibition. According to Brooks, Rothko told him that the "reason for his deep melancholy" (as characterized by Brooks) was that "his work had reached such an acceptance that it now inhabited the investment world as much as or more than the art world," with Rothko left "bereft of the only thing that meant anything to him - the love that many people had for his work. Now he no longer felt his work was admired for itself, but that it was a rising commodity quotation on the stock market." (RO412)

Stanley Kunitz:

... if Mark was working on a painting he would call up and say 'I want to show you something.' Then he would show you; he would stage it very carefully. The light had to be just right; everything had to be right. And he would watch your face while you looked at it. If your face didn't show exultation or if you didn't say anything, he would get very worried. Sometimes he would get a little angry even saying, 'I guess you don't like it.' " (RO416)

Articles about the exhibition appeared in Newsweek (January 23, 1961) and Time magazine (March 3, 1961). It was reviewed by John Canaday in The New York Times (January 22, 1961); by Robert M. Coates in The New Yorker (January 28, 1961); by Irving Sandler in Art International (March 1, 1961); by Katherine Kuh in the Saturday Review (March 4, 1961); by Robert Goldwater in Arts (March 1961); by Thomas] Hess] as "T.H." in Art News (March 1961); and by Max Kozloff in Art Journal (Spring 1961). (RO637-8fn12)

Rothko's sister, Sonia and his brothers Moise and Albert came to New York to see the exhibition. Sonia and Moise still lived in Portland and Albert worked as a translator for the CIA in Washington, D.C. (RO423)

Rothko's MoMA exhibition would be his last last solo exhibition during his lifetime. (RO459)

Max Kozloff:

"[Rothko] refused to show in this country any of the work he had done since his 1961 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, for fear it would be hostilely received. No one could persuade him otherwise, though many tried." (RO650fn1)

Robert Motherwell:

"[Rothko was] afraid to show his work, partly because he was afraid the new generation would find it ridiculous." (RO459)

February 1, 1961: Barnett Newman's brother dies.

Barnett became deeply depressed as a result of his brother's death. In order to coax his friend back to work, artist Cleve Gray invited him to make lithographs with Gray at the Pratt Institute Graphic Art Center. This was Newman's first experience with printmaking. He produced three black and white lithographs. Soon after completing the lithographs he painted the black-on-raw-canvas work, Shining Forth (to George) in memory of his brother whose Hebrew name had been Zerach ("to shine"). (MH)

February 6 - 25, 1961: Franz Kline exhibition at The Collector's Gallery in New York. (FK181)

On exhibit were Kline's 1940 Bleecker Street Tavern paintings and portrait drawings from the Minetta Tavern. (FK180)

An article on the Bleecker Street Tavern murals can be found here.

February 1961: Mark Rothko visits Dr. Grokest.

According to Grokest, Rothko told him "that he'd been living on alcohol for six weeks." Rothko suffered from high blood pressure and "wasn't sleeping" and had a vascular problem causing "blurry vision" and "shadowy forms" in his left eye. He also told the doctor that he was getting sedatives from other doctors. Grokest prescribed Surpicil to lower his blood pressure and chlorohydrate to help him sleep. (RO411)

February 26, 1961: Artists denounce The New York Times art critic John Canaday.

Canaday had been appointed the main art critic of The New York Times in September 1959 and, according to art writer Irving Sandler, "he immediately launched a campaign, more like a vendetta, against Abstract Expressionism." (IS241)

Irving Sandler:

"In January 1960, I took the lead in organizing a protest against Canaday's character assassination of us. I teamed up with John Ferren, and we invited a group of distinguished art-world figures to meet at his home... The participants decided to send a letter to the Times denouncing Canaday. De Kooning and Newman, with me as a kind of secretary, were designated to frame the letter. The three of us arranged to meet at my apartment. When we met, de Kooning and Newman began reminiscing about the old days and got so caught up in conversation that the letter never got written... I don't know who wrote the final letter, most likely Hess and Rosenberg, but Newman may have helped... The letter quoted scurrilous excerpts from Canaday's articles and concluded that they comprised the writing 'not of a critic but an agitator.' There followed a list of forty-nine signatories which included artists Stuart Davis, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hoffman, Robert Motherwell, and David Smith; art historians James Ackerman, Robert Rosenblum and Meyer Schapiro; composer John Cage; poets Edwin Denby and Stanley Kunitz; and philosopher William Barrett. The letter was published on February 26, 1961... He [Canaday] would later publish a book of his articles titled The Embattled Critic, using our letter as the pretext for his title."(IS242)

Spring 1961: Barnett Newman battles Erwin Panofsky in Art News.

The dispute was over the spelling of Sublimis in Vir Heroicus Sublimis. A photo caption for the work spelled the last word in the title as Sublimus. Newman defended the misprint as grammatically correct but that "the basic fact about a work of art... [is that] it must rise above grammar and syntax-pro gloria Dei." (MH)

April 13, 1961: Franz Kline is admitted into hospital.

Kline entered Johns Hopkins Hospital for tests and was told he had a rheumatic heart. (FK180)

April 14, 1961: Willem de Kooning buys more land in the Springs.

De Kooning purchased land owned by Elaine de Kooning's brother, Peter Fried who lived in a house next door, with the understanding that Bill would eventually buy the house as well. It was located on the Accabonac, across from the cemetery where Jackson Pollock was buried. De Kooning paid for the property with a painting. During the summer, Joan and Lisa stayed in the house and Bill went back and forth between the Springs and New York. (DK425)

April 25, 1961: Franz Kline hangs a show.

Kline helped to hang an exhibition of paintings, sculptures and prints by members of the New York City Bar Association which opened on April 25th at 42 West 44th Street. He received an honorarium of $200 and at the close of the exhibition was their guest at a dinner and party. (FK180)

May 1961: "Gottlieb" exhibition at the Galeria del Ariete in Milan, Italy. (AG173)

End May 1961: Franz Kline attends 30th reunion of Lehighton High School. (FK180)

June 21, 1961: Franz Kline buys a townhouse.

Kline purchased a brick townhouse at 249 West 13th Street which adjoined the back of his 14th Street studio. (FK180)

September 1961: Barnett Newman offers $500 to the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Barnett Newman, who was against juried exhibitions, sent a cheque to the Carnegie Museum offering to establish a five-hundred-dollar "Barnett Newman Award for an Artist Not Invited to the Pittsburgh International." His cheque was returned. (MH)

October 2 - October 12, 1961: Mark Rothko visits England. (RO412)

Rothko traveled by boat for the opening of his exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery where his MoMA exhibition was shown from October 10 - November 12, 1961. (RO411)

He had previously sent detailed instructions on how his work should be hung - oral instructions that were transcribed by someone at The Museum of Modern Art. (RO636fn2) The instructions noted that the gallery walls should be "considerably off-white with umber and warmed by a little red" and "the larger pictures should all be hung as close to the floor as possible," except for the Seagram murals which should be hung as they were painted - 4 1/2' from the floor. He added that the "light, whether natural or artificial, should not be too strong," as "The pictures have their own inner light and if there is too much light, the color in the picture is washed out and a distortion of their look occurs. The ideal situation would be to hang them in a normally lit room - that is the way they were painted. They should not be over-lit or romanticized by spots; this results in a distortion of their meaning. They should either be lighted from a great distance or indirectly by casting lights at the ceiling of the floor. Above all, every picture should be evenly lighted and not strongly." (RO412)

Bryan Robertson [director of the Whitechapel]:

"He asked me to switch all the lights off, everywhere; and suddenly, Rothko's colour made its own light: the effect, once the retina had adjusted itself, was unforgettable, smoldering and blazing and glowing softly from the walls - colour in darkness. We stood there a long time and I wished everyone could have seen the world Rothko had made, in those perfect conditions, radiating its own energy and uncorrupted by artifice or the market place." (RO412)

While he was in London, Rothko met Italian collector Count Guiseppe Panza di Biumo who was interested in purchasing five of the Seagram murals. By October 1960, the Count owned one Rothko - by September of 1961 he owned six and had expressed a desire to devote his collection in his Villa Litta (in Varese) "almost exclusively" to Rothko's work. During their meeting in London, Rothko agreed to sell him additional paintings to be selected when the Count was due to be in New York in late October.

The Count eventually selected five of the Seagram murals at $20,000 each and assured the artist they would be exhibited together in one room. A monthly payment schedule was set up. Two years later he changed his mind, blaming the "bad business conditions in Italy," after having already paid Rothko approximately $40,000. He suggested that he receive two individual paintings instead of the murals. He chose two "bright paintings" which he said were "more in balance with the dark ones" he already owned. Rothko suspected that his backing out of the purchase may have had to do with Pop Art. The Count had made several purchases at Claes Oldenburg's The Store (see below) and had purchased works by James Rosenquist and Roy Lichtenstein. (The Count did, however, stop buying art from 1962-1966 which he attributed to the Italian economic crisis of that period.) (RO432-33)

October 18-December 31, 1961: "American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The exhibition included Barnett Newman's Onement VI.

Irving Sandler:

"Barney was a first-generation Abstract Expressionist, but during the fifties, he was patronized in downtown circles. He began to paint seriously only in 1945, which was rather late. For much of the 1940s, he was perceived in the art world as an art writer and a spokesman for avant-garde artists... Our attitude to Barney's abstraction began to change around 1959, when he had a show at the French and Company Gallery. Then, in 1961, a single picture of his in the Abstract Expressionists and Imagists show at the Guggenheim Museum, the unforgettable Onement #6 [Onement VI], opened my eyes wide - and those of many of my contemporaries... Prior to the Guggenheim show I had already begun to interview Barney in preparation for my book on Abstract Expressionism... Barney spoke about his appreciation of Pissarro and Monet and his dislike of Cézanne... Alluding to the bulk of Cézanne's apples, Barney said: 'I objected to his cannon balls. Compared to the Impressionist idea of an even surface with no edges, Cézanne's weighty images are counterrevolutionary. But his watercolors really come off. Pissarro and Monet have been overlooked, but they changed painting.'" (IS285-6)

Barnett Newman:

"My hat goes off to the Impressionists because they moved into a new subject matter. They insisted that their subjects be chosen from secular life but claimed that they were as important as any crucifixion. This was a stupendous step."

c. Late 1961: Willem de Kooning punches Clement Greenberg.

During the run of the "Abstract Expressionists and Imagists exhibition" (see above) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Greenberg delivered a lecture, "After Abstract Expressionism." in which he spoke with "condescension" about de Kooning's recent work. About a month after the talk, de Kooning and Greenberg ran into each other at Dillon's where each was having lunch. There are various accounts of the meeting but the end result was the same: de Kooning punched Greenberg. (DK435)

From de Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

"... in October 1961, a show titled 'The American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists' opened at the new Frank Lloyd Wright building of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. The curator, H. Harvard Arnason, emphasized the color-field abstraction of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, both admired by Greenberg, rather than the work of de Kooning's followers. As Florence Rubenfeld wrote in her biography of Greenberg, 'Politically, Arnason's exhibition signaled the end of action painting's long reign and the ascendance of antigestural abstraction. It signaled the decline of the de Kooning/Kline influence, the Artists' Club and the Tenth Street phenomenon.'

At the time of the Guggenheim show, Greenberg gave a lecture at the museum called 'After Abstract Expressionism' in which he spoke with condescension about de Kooning's recent work. About a month later Greenberg and de Kooning met by chance at Dillon's, where each was having lunch. Their respective accounts differed about what happened. As reported by the writer Lionel Abel, who heard the story from de Kooning, Greenberg 'came up to him as he sat at the bar and made the accusation, 'Why do you tell people that I got my ideas from you?' Bill said that he realized Clem intended to to hit him, and so he thought it best to get in the first blow. He hit Greenberg on the jaw and the the two were separated.'" (DK435)

Clement Greenberg:

"In actuality what happened was that I was with Jim Fitzsimmons and Kenneth Noland, and Bill came in with a couple - new people to me - and they went to sit in a booth. We were at a table. He left his companions and came over to me and said, 'I heard you were talking at the Guggenheim and said that I'd had it, that I was finished.' Well, yeah. I had said that. Sure. I meant it too. And I still think that he was finished. He hasn't done a good picture since 1950 or '49. Anyway, Bill sat down with us... He just left his companions sitting alone in the booth. That was Bill. He was a barbarian like his wife, Elaine... no manners. Supposedly manners went out in the sixties, but at the Cedar Street Tavern they went out long before that.

Then I said, my voice going to falsetto, 'So what did I get out of it? So what did I get out of it, you son of a bitch?' And he took his elbow and poked me. It didn't hurt. He got up and punched me lightly while he was standing. So I got up to go after him and then we were separated. There was a scuffle in the separation because the kids - the louts who had been watching - all took his side. He was the hero down there. It took Ken Noland to intervene, to pull somebody off me. Then the next thing - they'd rushed Bill to the back of the bar. And then he was allowed to come back and he said, 'I'm not scared of you. I'm not scared of you.'" (DK435-6)

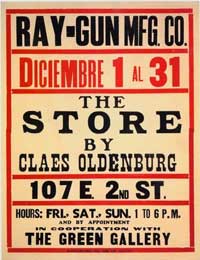

December 1, 1961: Claes Oldenburg opens "The Store." (RO429)

Prior to opening "The Store" at its own address, Oldenburg had exhibited a "Store" installation at the "Environments, Situations, Spaces" show at Martha Jackson's gallery from May 25 - June 23, 1961. (CO201)

From Blam! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism, and Performance 1958 -1964 by Barbara Haskell.

"'The Store' took the form of brightly painted plaster reliefs of everyday commodities - shoes, foodstuffs, fragments of advertising signs. Suspended in the stairwell and front window of the gallery like a random display in a messy shop window, 'The Store' manifested Oldenburg's increased involvement with commercial and manufactured objects. In contrast to the charred and torn relics of his 'Street,' these plaster reliefs were blatantly commercial in subject... it was about buying and selling.

Oldenburg's next version of 'The Store' posed even more penetrating questions about the relationship between art and commerce. For two months beginning in December 1961, he ran a 'business' in an actual storefront on East Second Street under the aegis of the Ray Gun Mfg. Co. Using the typical small business as his model, he sold plaster re-creations of foodstuffs and merchandise in the front half of the shop, while replenishing the inventory in his studio in the rear. In this way, Oldenburg conflated art and commerce... When Oldenburg opened the next incarnation of 'The Store' at Richard Bellamy's Green Gallery in September 1962, he further equated objects and human anatomy. His sculptures were now on a human scale and soft - sewn out of canvas and stuffed with kapok in a manner reminiscent of the props in his Happenings." (BM69-71)

The poster advertising the second version of Oldenburg's "The Store" gave the address as 107 E. 2nd Street - Oldenburg's studio - and the dates of the exhibition as December 1 to 31 although it was extended through January. (CO201) Oldenburg came up with the idea for "The Store" while driving around New York City.

Claes Oldenburg:

"I drove around the city one day with Jimmy Dine. By chance, we drove through Orchard Street, both sides of which are packed with small stores. As we drove, I remember having a vision of 'The Store'. I saw, in my mind's eye, a complete environment based on this theme. Again, it seemed to me that I had discovered a new world. I began wandering through stores - all kinds and all over - as though they were museums. I saw the objects displayed in windows and on counters as previous works of art." (LP66)

One of the visitors to "The Store" was Andy Warhol who would recreate his own choice of a foodstuff on canvas - albeit a more realistic representation of a foodstuff - a soup can.

December 1961: Mark Rothko donates Number 19, 1958 to The Museum of Modern Art.

In a note to Alfred Barr dated December 14, 1961, Rothko stipulated that the gift be anonymous and that the painting "not be lent or shipped for exhibitions and that it "shall not be offered for sale, or given away by the Museum." Barr wrote back on December 22, 1961 agreeing to the terms except for the stipulation that the painting should not be given away. Future trustees could not be bound by such a restriction. He suggested, instead, that Rothko stipulate two institutions to which the museum could give the painting if it was no longer wanted. Rothko wrote back on December 27, 1962 naming (1) the Mark Rothko Foundation and (2) the Phillips Collection. (RO669-70n23)

Late 1961/62: Willem de Kooning has an affair with Marina Ospina.

De Kooning and Marina had a brief affair. She was married at the time but had separated from her abusive husband. Bill helped her out with money, including paying her hospital bills after a beating. She left New York in late 1962 for Florence and wrote Bill over the next year. In early 1964 she begged him for money saying that she "nearly killed myself" and "Frankly speaking Willem I've very bad off and was wondering if you would help me. That's why I ask myself if you still remember me and the wonderful times we had together. I was happy then two years ago. Now I have nothing." (DK427)