American Expressionism 1951

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

"The police report noted: 'Jackson Pollock... driving a 1941 Cadillac convertible... went off North side of road, hitting three mailboxes (in triangle of intersection) of Louse Pont Road... hitting telephone pole #30 with right front wheel, continuing for 55 feet in a SW direction, hitting a tree head on.'"

1951: Viking Press publishes Abstract Painting, Background and American Phase by Thomas Hess. (FK178)

1951: Wittenborn-Schultz publishes Modern Artists in America (Ser. 1) edited by Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt. (AG172)

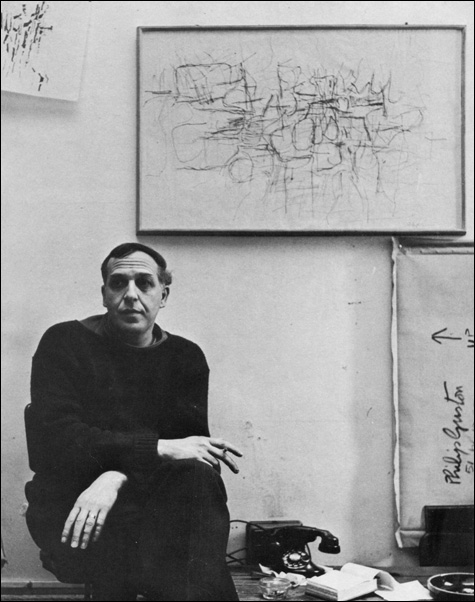

1951: Philip Guston paints White Painting.

Philip Guston in his studio in his Tenth Street studio, NYC, c. 1951 (MM)

(Photographer unknown)

Musa Mayer, his daughter, later recalled that after Guston took a studio in Manhattan in 1949, "his depression had lifted, and the notion of painting as process began to obsess him."

Musa Mayer [Philip Guston's daughter]:

He began painting the first completely abstract paintings of his career... by 1951, the work had become spare and spacious... Bare canvas began to appear, drips and impasto that attested to a new spontaneity... White Painting, 1951, was the pivotal work, the new beginning. (MM48)

Philip Guston: [1966]:

I wanted to see if I could paint a picture - have a run, so to speak - without stepping back and looking at the canvas and to be willing to accept what happened, to suspend criticism. Instead of walking back, pulling out a cigarette and thinking, to not suspend my own endeavors, but to test myself, to see if my sense of structure was inherent. I would stand in front of the surface and simply keep on painting for three or four hours. I began to see that when I did that, I didn't lose structure at all. (MM49)

1951: "Contemporary Paintings in the United States" at the County Museum in Los Angeles.

Included Mark Rothko, John McLaughlin, Emerson Woelffer, Calvert Coggeshall and Rico Lebrun. (RO298)

January 1951: Jackson Pollock spends a drunken winter in New York.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner stayed in New York after Pollock's exhibition at the Betty Parson's Gallery closed on December 16, 1950. They stayed again at Alfonso Ossorio's carriage house at 9 MacDougal Alley. On January 6, 1951 Pollock wrote to Ossorio (who was in Paris), "I found New York terribly depressing after my show - and nearly impossible - but am coming out of it now." Toward the end of January he sent another letter - "I really hit an all time low - with depression and drinking - NYC is brutal. (JP215)

Jackson was known to hang out at the Cedar Street Tavern and art students and groupies would gather there in wait. One student-admirer of Jackson recalled that when she finally met her idol at the bar, she was disgusted when he "pulled my behind and burped in my face." (JP217) Dan Rice, a young painter, recalled one night when he and Franz Kline brought Pollock home drunk and Krasner was standing at the top of the stairs screaming "Don't bring him up. I don't want a drunk in my bed!" Lee rarely accompanied Jackson to the Cedar. She would later say "I loathed the place. The women were treated like cattle." (JP218)

Jackson did what he could to make up to Lee for his drunken behaviour. One day he returned home with a will that left his estate to Lee - "If my wife, Lee Pollock, survives me then I give, devise and bequeath to her my entire estate." He also tried to get her an exhibition at Betty Parsons' gallery. "I don't show husbands and wives," Parsons initially told him, although she did give Krasner a show in October (see below). (JP218)

While in New York, Pollock also wrote and recorded a short narration for Hans Namuth's color film of him painting. Together he and the producer of the film wrote a six minute statement based mostly on earlier statements, beginning with "My home is in Springs, East Hampton, Long Island. I was born in Cody, Wyoming thirty-nine years ago." He objected, however, when co-producer Paul Falkenberg added Balinese gamelan music to the film's soundtrack, reminding Paul that he was an "American painter." When the eleven minute documentary was shown at The Museum of Modern Art in the summer it was accompanied by music by Morton Feldman, an American composer from Brooklyn.

Jackson also managed to complete a few dozen ink drawings while in New York, most of which were used for collages or as part of a sculpture (untitled) which was exhibited at the Peridot Gallery on Twelfth Street in a group exhibition titled "Sculpture by Painters." Betty Holiday (as B.H.) wrote in Art News (April 1951), "Jackson Pollock stops the show with a writhing, ridge-backed creature." When the show closed he went to pick up the sculpture. When it wouldn't fit in the trunk of the car he flattened it by stomping on it and later threw it away. (JP220)

January 2 - 22, 1951: "Gottlieb: New Paintings" at the Kootz Gallery. (AG173)

January 5, 1951: Arshile Gorky memorial exhibition opens at the Whitney Museum.

("Many Art Shows Opening in Week," The New York Times, January 1, 1951, p. 15)

January 6, 1951: Virgil Thomson speaks at the Club. (NE161)

January 9, 1951: Party for Conrad Marca-Relli at the Club. (NE161)

According to Philip Pavia it was a party for Marca-Relli "after his opening at Kootz," yet according to Adolph Gottlieb: A Retrospective (NY: The Arts Publisher, Inc., 1981), Kootz was showing "Gottlieb: New Paintings" from January 2 - 22.

January 11 - February 7, 1951: "Seventeen Modern American Painters: The School of New York" exhibition at the Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills, California.

From the catalogue preface by Robert Motherwell:

The recent "School of New York" - a term not geographical but denoting a direction - is an aspect of the culture of modern painting. The works of its artists are "abstract," but not necessarily "non-objective." They are always lyrical, often anguished, brutal, austere, and "unfinished," in comparison with our young contemporaries of Paris; spontaneity and a lack of self-consciousness is emphasized... (SG204)

January 12, 1951: "Art in Anti-artistic Times" at the Club, with speaker Heinrich Blücher.

The talk was on the third volume of André Malraux's book. According to Philip Pavia, "Clement Greenberg, Barney Newman and Meyer Schapiro were one hundred percent against Malraux." (NE161)

January 19, 1951: "Space, Math and Modern Painting" at the Club with speaker J. Van Heijenoort, introduced by Willem de Kooning. (NE161)

January 23 - March 25, 1951: "Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America" at The Museum of Modern Art. (PP326)

Out of the 108 works in the show only twelve came from the museum's collection. Artists included Joseph Stella, Patrick Henry Bruce, John Covert, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Motherwell, William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Jimmy Ernst, Kamrowski and Charles Seliger. The works were categorized under headings such as "pure geometric," "naturalist geometric" and "expressionist biomorphic" in the catalogue. (SS414)

Included de Kooning's Excavation. (DK307), Mark Rothko's Number 14, 1949 (RO299) and Jackson Pollock's Number 1A, 1948. (PP326)

January 15, 1951: The Irascibles appear in Life Magazine.

The headline for the article was "IRASCIBLE GROUP OF ADVANCED ARTISTS LED FIGHT AGAINST SHOW."

See November 26, 1950: The Irascibles sit for their Life magazine photo session.

January 29 - February 7, 1951: Mark Rothko takes a class at Art Students League. (RO615fn43)

Rothko took a class in etching and lithograph techniques taught by Will Barnet at the League in preparation for teaching a Graphic Workshop at Brooklyn College. (RO289)

February 2, 1951: "The Unframed Frame: Modern Music" at the Club with speaker Morton Feldman.

Philip Pavia paraphrased Feldman's talk as "Jazz is too instrumental, not human; music needs a plane as in painting." (NE161)

First week of February 1951: Mark Rothko begins teaching at Brooklyn College.

Rothko taught in the Design Department for seven semesters at the college (RO290) at a salary of about $5,000 a year on a three year contract. (RO289/291) He taught Graphic Workshop, Contemporary Art, Theory of Art, Elements of Drawing and a course in Color which he made into a painting workshop. (RO289-90) Murray Israel recalled that Rothko began his Contemporary Art course with Rembrandt - "he felt that Rembrandt represented the first time an artist painted whatever he felt like doing." (RO291) Unlike Rothko, many of the other members of the faculty embraced the Bauhaus philosophy - which Rothko would criticize for filling our "cultural vernacular" with "false and facile chatter." (LM27)

February 1951: Willem de Kooning explains "What Abstract Art Means to Me."

The talk was part of a symposium organized by the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with their "Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America" show. (DK325)

February 7, 1951: Jackson Pollock visits Chicago.

An arts group called Momentum had invited Pollock to jury an exhibition. He traveled by plane for the first time. Although he enjoyed the flight he wasn't so keen on that art. He wrote to Alfonso Ossorio "The jurying was disappointing and depressing - saw nothing original being done." (JP219)

February 9, 1951: "Something and Nothing" at the Club, with speaker John Cage.

Philip Pavia characterized this talk as "Zen coming into the Club." (NE161)

February 16, 1951: Homage to Arshile Gorky at the Club. (NE161)

February 23, 1951: "Psychology, Religion and Creativity" at the Club, with speaker Henry Elkin. (NE161)

March 1951: Cecil Beaton uses Jackson Pollock's paintings for a fashion spread in American Vogue magazine.

Beaton used Pollock's 1951 one man show at the Betty Parsons gallery as a location for a fashion shoot that appeared in the March 1, 1951 issue of Vogue.

(SG248fn31)

March 1, 1951: "Art and Architecture, Setting" at the Club.

Speakers were Harry Holtzman, Philip Johnson, Frederick Kiesler, Sybil Noholy-Nagy. (NE161)

March 8 - 31, 1951: Jackson Pollock shows in Paris. (PP326)

Pollock's Number 8, 1950 was included in a group show, "Vehemences Confrontees," organized by French critic Michel Tapie at the Galerie Nina Dausset, Paris. (PP326)

March 9, 1951: "Artists should be Homosexual" at the Club.

The talk was presumably tongue-in-cheek. Philip Pavia recalled that Harold Rosenberg "didn't think this was funny." (NE161) The speaker was a friend of Rosenberg, the architect Percival Goodman, who, by the time of his death, had a wife, two sons and a daughter.

Harold Rosenberg would be quoted on homosexuality in the arts in a 1966 Time magazine article:

From "Essay: The Homosexual in America" (Time magazine, January 21, 1966):

On Broadway, it would be difficult to find a production without homosexuals playing important parts, either onstage or off. And in Hollywood, says Broadway Producer David Merrick, "you have to scrape them off the ceiling." The notion that the arts are dominated by a kind of homosexual mafia—or "Homintern," as it has been called—is sometimes exaggerated, particularly by spiteful failures looking for scapegoats. But in the theater, dance and music world, deviates are so widespread that they sometimes seem to be running a kind of closed shop. Art Critic Harold Rosenberg reports a "banding together of homosexual painters and their nonpainting auxiliaries..."

Homosexual ethics and esthetics are staging a vengeful, derisive counterattack on what deviates call the "straight" world. This is evident in "pop," which insists on reducing art to the trivial, and in the 'camp' movement, which pretends that the ugly and banal are fun.

March 21, 1951: Party for Hans Hofmann at the Club after his opening. (NE162)

March 23, 1951: Lecture on "The European Intellectual" dealing with art and politics by Hannah Arendt at the Club. (NE162)

March 30, 1951: "Art and Sex" at the Club with speaker Gerson Legman, editor of the magazine Neurotica. (NE162)

April 1951: Willem de Kooning's second show at the Egan Gallery. (DK315)

Much of the exhibition consisted of black and white paintings not sold at the previous show. Again, there were few buyers. By June only three drawings and two paintings had been sold. (DK315) According to Egan's wife, Betsy Duhrssen, "Bill didn't get his money. Charlie would sell something and then the money would go to the rent or to drinks... Well, Bill was starving. He ate at the Automat. Elaine claimed that sometimes he just ate catsup." When Egan had first become engaged to Duhrssen, he told her mother that instead of spending $1,000 on her wedding gift for a hi-tech record player, she should buy the couple a work of art from the gallery. She purchased de Kooning's Light in August from the 1948 show. Duhrssen's mother paid $750 for the work but de Kooning never received any of the money. (DK315)

c. March/April 1951: Mark Rothko's final exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery - MoMA acquires Number 10, 1950, painted in 'classic' Rothko style.

"Recent Paintings" was Rothko's last show at the gallery. Clyfford Still referred to Rothko's work in the show as "the work of a very great man and I do not use the term with abandon. I consider myself one of the specially favored to know and to perceive this power and to have seen and I think understood its genesis and development." (RO223)

Prices ranged from $500 - $3,000. Rothko sold only one painting during 1951 - Number 10, 1950 - which was one of the works shown (under the name Number 10, 1951). It was sold to Philip Johnson for $1,250 (despite the asking price of $1,500) who then donated it to The Museum of Modern Art. Alfred Barr wanted the painting for the museum but thought that the trustees wouldn't approve the purchase so he asked Johnson to buy the painting and give it to the museum. One of the founders of the museum, A. Conger Goodyear, resigned in protest at the acceptance of the gift. (RO298/299/616n7)

With Number 10, 1950, a large canvas measuring 7 1/2' x 4 3/4', Rothko's style had evolved from multiforms to the 'classic' format that he is now most associated with. Rothko biographer James E.B. Breslin notes that that "In paintings like Number 10, 1950, Rothko creates not just a recognizable image but a personal icon, 'a new structural language' flexible and rich enough to engage - or obsess - him for the next fifteen years." (RO276-7)

April 6, 1951: Talk on Leon Battista Alberti at the Club with speaker Harold Acton. (NE162)

April 13, 1951: Talk on "Magic" at the Club with speaker Kurt Seligman.

Philip Pavia described the evening as "Surrealism comes back." (NE162)

April 18, 1951: Discussion/Members Only at the Club. (NE162)

April 23, 1951: Barnett Newman's second solo exhibition opens.

Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Tony Smith installed the show. Works included Newman's first 18 foot long painting, Vir Heroicus Sublimis.

Nothing sold and critical reaction was negative. In the months following the exhibition Newman removed his work from the gallery and withdrew from all gallery activities. (MH)

April 27, 1951: "Myth and Creative Art" at the Club, with speaker Joseph Campbell, introduced by Leo Castelli.

Philip Pavia explained "Myth as a subject matter was similar to Jungianism and primitivism." (NE162)

c. Spring 1951: Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still ask Betty Parsons to drop her other artists. (RO297)

The meeting took place over dinner at Betty Parsons' fifth floor studio apartment on East 40th Street. There are various accounts of who attended the meeting. Parsons herself recalled only the presence of Newman, Pollock, Rothko and Still. Alfonso Ossorio recalled being at the meeting which (according to him) was also attended by Newman, Rothko, Bradley Tomlin, Herbert Ferber, Seymour Lipton and one other painter but not Clyfford Still - in at least one account he gave. In another account Ossorio recalled that Still was in attendance. The authors of Jackson Pollock, An American Saga also included Ad Reinhardt at the meeting. (RO616n1)

Betty Parsons:

They [Newman, Pollock, Rothko and Still] sat on the sofa in front of me, like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and suggested that I drop everyone else in the gallery, and they would make me the most famous dealer in the world... But I didn't want to do a thing like that. I told them that, with my nature, I liked a bigger garden. (RO297)

The date of the meeting is also confused. Rothko biographer, James E.B. Breslin, says that it took place during the 1951/52 art season, yet Barnett Newman left Parsons' gallery (on friendly terms) after his April 1951 show. As Newman was presumably still signed to the gallery at the time of the meeting, the meeting would have had to have taken place earlier than the 1951/52 art season which began in the autumn of 1951.

Although some accounts of the Parsons' meeting with the artists tend to give the impression that the artists left Parsons' gallery when she would not acquiesce to their demand, their departures actually occurred over the next few years and when they left, they left as individual artists rather than as a group. Rothko didn't leave the gallery until the spring of 1954. On September 27, 1954 he wrote to Katherine Kuh that "As I had informed you at our last meeting in New York, my relationship with the Betty Parsons Gallery was terminated last spring." (RO616n6) Newman left the gallery (on friendly terms) after his April 1951 show. By May 1952 Jackson Pollock had moved to the Sidney Janis Gallery across the hall from Parsons. (Worried that other artists might join him, she bought three works by Still and three by Rothko herself with a gift of $5,000 from a friend. (RO297)) By December 1953, Still signed with Janis without telling Parsons.

Although the three joined together to give the ultimatum, their friendship would soon begin to fall apart. Newman would blame Rothko for not pushing hard enough to have his work included in the "Fifteen Americans" show in 1952 and Still would later pinpoint 1951 as the year he began his repudiation of Newman. In a letter to curator and art writer Katherine Kuh dated October 22, 1965 Still noted that his falling out with Newman began in 1951:

Clyfford Still:

When I took up residency in New York in 1950, I slowly discovered the range and depth of [Newman's] schemes. And during 1951 I began my repudiation of him and what I had to call the Parsons gang. However, much damage was done by that time and the violation continues to this day in spite of my efforts to separate the free and creative from the parasitical and authoritarian. (RO622fn46)

Katherine Kuh later recalled that "Rothko adored Still to his dying day. He never repudiated Clyff, never. However Clyff repudiated Rothko... Mark would always ask me [after Still moved to Maryland in 1961], 'When are you going to see Clyff again?' Always. Clyff was on his mind all the time. Mark would say 'Remember me to Clyff.' And then when I'd come back, he'd say, 'What did he say about me?' like a little boy." (RO347-48) After Rothko persisted, Kuh told him what Still had told her: "Well, he said you're living an evil, an untrue life." (RO348)

Irving Sandler:

Still showed Rothko and Newman the way to color-field abstraction. The three painters had been close friends in the late 1940s, but in the 1950s they had a falling out. Still broke with Rothko when he wouldn't join him in a campaign against the market mentality in the art world... Still and Newman stopped seeing each other when they began an unseemly squabble over who did what first... The arm-wrestling over priority between Still and Newman became so sweaty that both began to push back the dates of their works. Still began to date paintings from the inception of the idea. Newman was as brazen. Late in 1949, [The] Tiger's Eye reproduced his The Break, dated 1948... The reproduction was obviously dated by him since he was an editor of the magazine. He later painted '1946' onto its surface. (IS98)

Elaine de Kooning:

... Clyfford Still and Rothko at one time were friends. But Clyfford Still's surface, his shapes, his attitude as exemplified by his painting, had absolutely nothing to do with what Rothko was doing. Mark Rothko was interested in transparencies. Transparency is a word that Clyfford Still never heard of. I mean, Clyfford Still was not only opaque, they're dense. And they're not only dense, they're impacted. So there just is no relation. Possibly, philosophically, theme was a relation. People can influence an artist. Other artists can influence an artist, not in terms of the work but in terms of words-what we were just talking about. And Rothko was very influenced in certain ways by-what's the name of that artist who paints beach scenes? (SE) [Note: the "artist who paints beach scenes" was Milton Avery.]

May 1951: Art News publishes "Pollock Paints a Picture." (PP326/PK74)

Included text by Robert Goodnough, five photographs by Hans Namuth showing Pollock at work on Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950 and a photograph by Rudolph Burckhardt of cans of paint on the floor of the studio. (PP326) Goodnough and Burckhardt had visited Pollock the previous year, in June, and had followed his progress as he pretended to paint a work of art (see June 1950) which is called Number 4, 1950 in the article. Goodnough notes about the painting, it "was begun on a sunny day last June." (PK74)

A selection of Hans Namuth's photographs of Jackson were also published in Portfolio: The Annual of the Graphic Arts (George S. Rosenthal and Frank Zachary (eds), 1951).

Spring 1951: Sidney Janis supports Willem de Kooning.

Janis began advancing money to de Kooning for art supplies. De Kooning would officially change over to the Janis Gallery in 1953. (DK319)

May 2, 1951: Informal roundtable/open discussion session for members at the Club. (NE162)

May 4, 1951: Concert, music of Pierre Boulez, performed by David Tudor (pianist) with the Juilliard String Quartet at the Club.

May 9, 1951: Roundtable/informal session for members at the Club.

c. May 1951: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner return to the the Springs, East Hampton.

The May 10th East Hampton Star noted that "Mr. and Mrs. Jackson Pollack [sic] have returned to their home after spending the winter in Chicago and New York." (JP221)

[Note: According to B.H. Friedman in Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible the Pollocks returned to the Springs in late January and that "for the balance of the winter and spring, the Pollocks were in and out of New York." (JF170/172)]

In August Pollock wrote to Alfonso Ossorio, "This has been a very quiet summer... no parties hardly any beach - and a lot of work." (JP223)

Pollock was busy preparing for his next show at Betty Parsons Gallery, painting twenty-eight paintings for the show from May to September. The works were titled Number 1 through Number 28. (JP223) At at time when Pollock was being lauded for his allover abstractions he introduced figuration back into his art.

May 11, 1951: Informal talk by Clement Greenberg at the Club.

Described by Philip Pavia as "Opinions on everything (the frame, the weave), made fun of painting. (NE162)

May 18, 1951: "Art and James Joyce" at the Club with speaker Nat Halper.

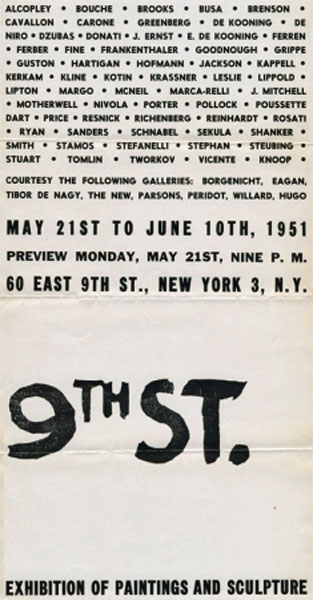

May 21 - June 10, 1951: Ninth Street show at 60 East 9th Street. (PP326)

Poster for the 9th St. Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture

Sixty-one artists were listed on the exhibition announcement/poster which was designed by Franz Kline. (FK178) According to Kline biographer Harry F. Gaugh, Kline's black and white abstraction, Ninth Street, took its name from the show. (FK178). Although Leo Castelli would later refer to the exhibition as "a celebration of Abstract Expressionism" (AD86), it did not include any work by Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still or William Baziotes. (IS38/9) Jackson Pollock was represented by Number 1, 1949 (PP326) and de Kooning by Woman (1949-50).

According to Gaugh, the exhibition was organized by "[John] Ferren, Marca-Relli, and Kline." (FK178) Most other accounts credit Leo Castelli with playing a key role in the organization of the show. Irving Sandler recalled " "With the help of Leo Castelli, a group of charter members leased an empty store at 60 East Ninth Street (next door to the studios of Kline, Marca-Relli and Ferren) for $70, and drew up an initial list of participants. " (IS38)

Leo Castelli:

The store was in terrible shape, but we all pitched in to clean it up. [Franz] Kline designed the announcement. I footed the bill, although everyone was supposed to contribute. However, some of the artists, de Kooning for example, gave me a drawing. Technically, inclusion was by invitation, but almost anyone who wanted in could get in. Pollock wasn't too interested but he did send a painting which was hung vertically instead of horizontally. It took about three days to install the show because artists came in and complained about the placement of their works. The show had a big sign on canvas which covered the whole front of the building. The opening was on a warm May day. There was a great crowd. Alfred Barr attended and was very surprised and excited. He wanted to know how the show came about and I went with him to the Cedar Street Tavern and we talked for a long time. The show was well attended. It closed on June 10. (IS38)

One of the artists Castelli chose for the show was Robert Rauschenberg:

Leo Castelli:

I decided to include Rauschenberg in that show, even though at the time the work seemed to have little to do with the Abstract Expressionist dogma. Perhaps it was an advance sign that I already saw beyond the Abstract Expressionists. For whatever reason, from then on I followed his career closely, and remember being overwhelmed by his show of 'red paintings' at Charlie Egan's Gallery the Christmas of 1954. (AD86-7)

The opening of the show seemed like a Hollywood premiere, despite the lack of coverage in the general press.

From de Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

Although the show was hardly noticed in the press, it became a fashionable event... For the opening, a banner was stretched across Ninth Street. A bare bulb in a flagpole socket illuminated the second floor. 'And that night the cars that arrived!' said [Joop] Sander[s]. 'The cabs that came! It was like, you know, the old newsreel pictures from a movie opening in Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood - people getting out in evening clothes.' Alfred Barr, for one, was stunned by the number of unfamiliar artists who were included. it confirmed for him and many others that what was happening in New York represented 'a movement' and 'a scene.' It was a historical phenomenon, in short, rather than just the expression of a few solitary and eccentric American voices. After the opening, Castelli took Barr to the Cedar and wrote down the names of the artists on the back of a photograph of the installation. Abstract Expressionist art would not begin selling well until the late fifties, but for Janis and others watching the art market, the Ninth Street show was a bellwether reminiscent of the Salon des Refuses, when the nineteenth-century Impressionists thumbed their noses at the official salon. Together with a series of powerful public statements - the Biennale in Venice, the Irascibles' attack upon the Metropolitan, and the celebration of American modernism at MoMA - the Ninth Street show represented the jelling of a style. People talked. And in art, money often follows talk. (DK319)

Thomas Hess reviewed the opening for Art News.

Thomas Hess [from "Review of the Ninth Street Show of 1951," Art News 50:46 (June 1951):

New York’s avant-garde [Ninth Street; to June 10] gathers spectacularly in a 90-foot former antique shop, newly whitewashed (by the exhibitors) for the occasion. An air of haphazard gaiety, confusion, punctuated by moments of achievement, reflects the organization of this mammoth show which, according to one of the organizers, 'just grew.' Some pictures were chosen by the artist himself; others picked by small delegations of colleagues. A few entries were accepted because 'so-and-so' is 'such a nice fellow'; a few because 'such-and-such' was a 'great help'; several for no conceivable reason whatsoever. Some out-of-town guests were invited; some in-town ones were simply forgotten; a number decided to make their absences conspicuously felt. But such hi-or-miss informality and enthusiasm has resulted in a fine and lively demonstration of modern abstract painting in and around New York - or, more properly, Greenwich Village. Authoritative statements come from De Kooning, Pollock, Franz Kline, Tworkov, Hofmann, Kerkam, Vicente, Brooks, Motherwell, McNeil, Cavalon, Reinhardt, and sculptors David Smith and Peter Grippe. Among the lesser-known painters - whose extensive representation will make this exhibition doubly interesting to specialists - we especially noted Resnick, E. de Kooning, De Niro, Farber and Sanders. A number of the others seemed amateurishly avant-garde, attempting to pick up technique which had been created to express complicated ideas, and simply elaborate cleverly upon it. Their results are pretentious, huge, but nevertheless dainty and feminine, despite all the slappings and dashings. Still other canvases make pleasant wallpaper for the many powerful works presented in this lively manifestation of energy and accomplishment.

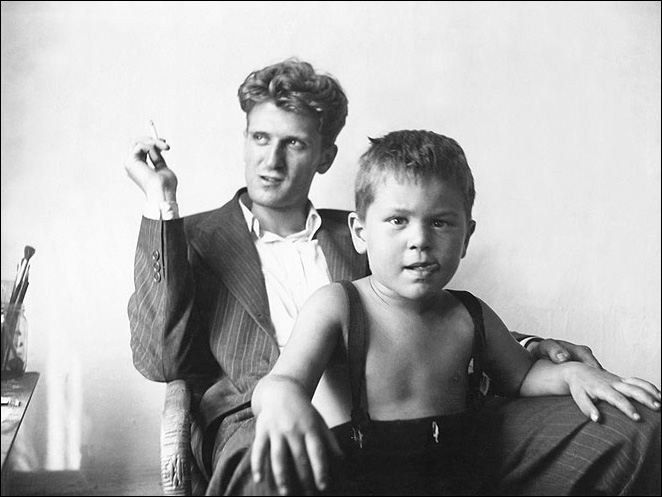

Robert De Niro Sr. (the artist) and Robert De Niro Jr. (the actor)

(Photographer unknown)

The artist referred to as "De Niro" in Hess' review was Robert De Niro Sr. His son of the same name would become the Academy Award winning actor Robert De Niro who got his first attention from the press after appearing in a production of Glamour, Glory and Gold written by Warhol star Jackie Curtis (see "Glamour, Glory and Gold," p, 2)

May 23, 1951: Club lecture on Picasso by speaker Henry Kahnweiler, at MoMA. (NE163)

May 25, 1951: "Music of Pierre Boulez" at the Club with speakers John Cage and Morton Feldman.

New Music Quartet with David Tudor, pianist, and Frances Manes, violinist. (NE163)

Summer 1951: Robert Motherwell teaches at the summer session of Black Mountain College.

It was his second summer session teaching at the college. He had previously taught there during the summer of 1945.

Robert Motherwell:

The second summer I was there the place was falling apart economically, spiritually, and every way. They supported themselves by having a big farm and had their own milk and corn and so on. I remember passionately arguing to them that the essential nature of the place was an avant garde college, that the natural place to draw on would be New York, and that they should sell this place in North Carolina and get a big farm on Long Island - everybody in North Carolina hated them - and that they'd have no difficulties at all. Which I'm sure is true. Then they would be a celebrated place now. But it reached the standpoint of internal friction, argument, decadence. Nobody could listen to anything. (SR)

June 4, 1951: "Forty American Painters, 1940-1950" at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Included Franz Kline.

June 7, 1951: Jackson Pollock paints it black.

Pollock wrote to Alfonso Ossorio on June 7th, "I've had a period of drawing on canvas in black - with some of my early images coming thru - think the non-objectivists will find them disturbing - and the kids who think it's simple to splash a Pollock out." (PP326)

June 8, 1951: Party at the Club in celebration of the Ninth Street Show. (NE163)

Philip Pavia ("Summary of 1951"):

The Ninth Street Show revealed the strength of abstraction and expressionism. Afterwards, the younger artists stormed the Club and the membership jumped from sixty to one hundred twenty. The Club became known for being avant-garde, and its name spread throughout the general culture.

This was also the time when the Cedar Tavern became popular. After the Club closed for the night, some artists would spill out to the Cedar for more conversation - before we were coffee drinkers. (NE165)

June 14, 1951: Hans Namuth film of Jackson Pollock premieres at The Museum of Modern Art. (PP326)

The film was co-produced and co-directed by Paul Falkenberg. (PP326)

June 15, 1951: "Heidegger and Need of the Time" at the Club with speaker William Barrett from Commentary magazine and New York University.

Described by Philip Pavia as "On Existentialism, much discussion followed." (NE163)

June 20, 1951: Discussion/Members only at the Club. (NE163)

June 26 - September 9, 1951: "Selections from 5 New York Private Collections" at The Museum of Modern Art.

Included Mark Rothko.

September 12, 1951: Meeting at the Club to discuss increased membership. (NE163)

Autumn 1951: "60th Annual American Exhibition: Paint and Sculpture" at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Willem de Kooning's painting Excavation won the first prize of $4,000 and was purchased by the Art Institute. De Kooning opened his first bank account with the check. (DK320)

September 19, 1951: Members only party at the Club to celebrate the beginning of the season. (NE163)

September 1951: Clyfford Still announces that he will no longer exhibit his paintings. (RO297-8)

September 26, 1951: Discussion/Members only at the Club. (NE163)

September 28, 1951: "An Inquiry into Avant-garde Art" with speaker Martin James at the Club. (NE163)

October 3, 1951: Business meeting at the Club. (NE163)

October 1951: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner stay in New York for two months. (JP224)

October 10, 1951: Discussion/Members only at the Club. (NE163)

October 12, 1951: "Collaboration of Art and Architecture" at the Club, with speaker Peter Blake, friend of Mercedes Matter.

Described by Philip Pavia as "More intermingling of the arts." (NE163)

October 15, 1951: Party at the Club for Peter Busa after his opening. (NE163)

October 15 - November 13, 1951: Lee Krasner's first solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (PP326)

None of the fourteen paintings sold.

October 17, 1951: Roundtable/members only evening at the Club. (NE164)

October 19, 1951: "Artists Answer to Collaboration of Art and Architecture" at the Club with speakers Willem de Kooning, Nicolas Calas and Ad Reinhardt.

Philip Pavia characterized the evening as "chaotic." (NE164)

October 23, 1951: The Club presents "How the United Nations Works" at the Baha'i Center. (NE164)

October 24, 1951: "Discussion as usual" at the Club - members only. (NE164)

October 26, 1951: "Teaching and the Artist" at the Club - moderated by John Ferren with speakers Robert Wolff, Robert Iglehart and Robert Richenburg. (NE164)

November 2, 1951: "Ideas and Form" at the Club with slide show and speaker Sybil Maholy-Nagy.

Sybil was the secretary to Oswald Spengler at the time. Philip Pavia comments "Bauhaus thinker, active back and forth on Spengler." (NE164)

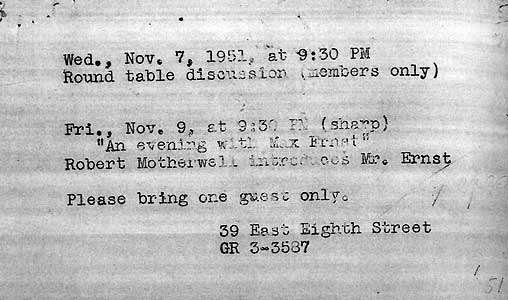

November 7, 1951: "Roundtable/Members only" at the Club. (NE164)

November 9, 1951: "An Evening with Max Ernst" at the Club, introduced by Robert Motherwell. (NE164)

Announcement for "An evening with Max Ernst" at the Club

November 14, 1951: "Discussion/Members only" at the Club. (NE164)

November 16, 1951: "Less Abstract Than Music" at the Club, with speaker Nicolas Calas. (NE164)

November 21, 1951: "Informal discussion/Members only" at the Club. (NE164)

November 23, 1951: "Modernity and the Modern World" with speaker Lionel Abel at the Club.

Philip Pavia described the evening as "About Paris and Breton, and that abstract art needs a free world." (NE164)

November - December 1951: Franz Kline's second solo exhibition at the Charles Egan Gallery.

Works included Painting No. 11 (1951) and Ninth Street (1951). (FK100)

November 26 - December 15, 1951: Jackson Pollock's fifth solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (PP326)

Twenty-one paintings were exhibited including Number 11, Number 14, Number 17, Number 18, Number 19 and Echo: Number 25, plus watercolours and drawings, all from 1951. The paintings incorporated black paint on apparently raw canvas with figurative imagery. (PP326) Pollock had written to Alfonso Ossorio in June, "I've had a period of drawing on canvas in black - with some of my early images coming thru - think the non-objectivists will find them disturbing - and the kids who think it's simple to splash a Pollock out." (PP326)

Only two paintings sold - for about $1200. During the exhibition someone scribbled obscenities on Number 7, 1951. When Charles Egan saw the artist at the show he commented, "Good show, Jackson, but could you do it in color?" (JP225)

Six of the black paintings were reproduced and printed as serigraphs in editions of twenty-five with the printing done by Jackson's brother Sande at his shop in Essex, Connecticut. Pollock told him, "All I want is five hundred dollars." (JP226)

A few days after the show closed, Jackson and Lee returned to the Springs. (JP227)

December 7, 1951: Lionel Abel at the Club.

Philip Pavia described the evening as "repartee with Esteban Vicente." (NE165)

December 12, 1951: "Roundtable discussion/Members only" at the Club. (NE165)

December 14, 1951: "Certain Aspects of Heidegger's Existentialism" at the Club, with speaker Hubert Kappel. (NE165)

December 26, 1951 - January 5, 1952: "American Vanguard Art for Paris Exhibition," at the Sidney Janis Gallery.

The show traveled to the Galerie de France in Paris from February 26 - March 15, 1952. The twenty artists included in the show were: Philip Guston; Matta; Loren MacIver; Josef Albers; William Baziotes; James Brooks; Willem de Kooning; Robert Goodnough; Arshile Gorky; Adolph Gottlieb; Hans Hofmann; Franz Kline; Robert Motherwell; Jackson Pollock; Morgan Russell; Ad Reinhardt; Mark Tobey; Bradley Walker Tomlin; Jack Tworkov; and Esteban Vicente.

Howard Devree noted in his review of the show in The New York Times that "since the close of the war the number of exhibitions of American art abroad has grown rapidly. Beside the exhibitions arranged through museums and those more or less sponsored by various government agencies, many of them in the nature of historical surveys of our painting, there was the representation of chiefly abstract work at the Venice Biennale in 1950, which aroused much interest and controversy. Last year work by members of the American Abstract Artists were shown in France, Italy and Germany with considerable success. The latest event to be arranged in this marked turning of the tide is an exhibition entitled 'American Vanguard Art for Paris Exhibition." (HD)

Howard Devree [from "Abstract Export; Controversial 'Vanguard' Work to Go to Paris," NYT (December 30, 1951) p. x9]:

Most of the well-known practitioners of this highly subjective painting are represented by work in extreme abstract idiom... Judgment upon all of the work in this direction cannot at the present time be final. Much of it is clearly experimental. Some of the artists seem to be in process of changing direction somewhat. In de Kooning's 'Woman' variations for example, and in some of the recently shown Pollock canvases, something more than a suggestion of recognizable figurative elements have been noted. Gottlieb's symbolism and the lyrically suggestive color forms of Baziotes are clearly not to be approached in quite the same spirit as the 'pure painting' by some of the others... Guston's previous linear and figurative designs have given way to a somewhat bleak gray background with shapes as of doors or windows opening on nowhere but with a dominant emotion recognizable. (HD)

December 28, 1951: Jackson Pollock wrecks his car.

The East Hampton police were notified at 10:00 pm of an automobile accident in the Springs. The police report noted: "Jackson Pollock... driving a 1941 Cadillac Conv... went off North side of road, hitting three mailboxes (in triangle of intersection) of Louse Pont Road... hitting telephone pole #30 with right front wheel, continuing for 55 feet in a SW direction, hitting a tree head on." The incident made the first page of The East Hampton Star (January 3, 1952): "Jackson Pollock, Artist, Wrecks Car, Escapes Injury." (JP227)