Jerome Hill and Charles Rydell

by Gary Comenas (2016)

page one

Jerome Hill (b. March 2, 1905) was a filmmaker, painter and patron of the arts who, along with his younger friend Charles Rydell (b. October 28, 1931), was at one point part-owner of Andy Warhol's Interview magazine.

Warhol biographer, Fred Lawrence Guiles, identifies Charles Rydell as Hill's "lover." (LB409) In a biographical essay about Hill published by the Jerome Foundation, art writer Mary Ann Caws notes that Hill handled his homosexuality "with great delicacy" and that his "sense of apartness" was "in large measure attributed to his sensitivity about his homosexuality." (MAC19) (MAC11).

The Jerome Foundation

In 1964 Hill set up a philanthropic organization, the Avon Foundation, which was renamed the Jerome Foundation after his death. (MAC15) The Foundation continues to support the arts. In 2016 it helped to fund the New York Art Book Fair at which Jonas Mekas made an appearance on September 18, 2016.

Jerome Hill meets Charles Rydell meets Andy Warhol

Hill had a privileged upbringing. His grandfather, James Jerome Hill, created the Great Northern Railway and the First National Bank of Saint Paul. Jerome and his siblings were educated at home. His interest in filmmaking may have been influenced by the screening of films at the family home. His parents would show films at home because they had a "horror of the microbes that might be proliferating in public places, like movie houses." (MAC6)

Hill's "lover," Charles Rydell, had anything but a privileged upbringing. According to Fred Lawrence Guiles, "When he was a small boy, Charles had been put in a boys' home because his father was alcoholic and his mother and aunt were 'thrown out of Pennsylvania because they were prostitutes.' Some money was stolen and the head of the home wrongly accused Charles and then he had to run a gauntlet of paddles. He never got over his sense of injustice." (LB229-231)

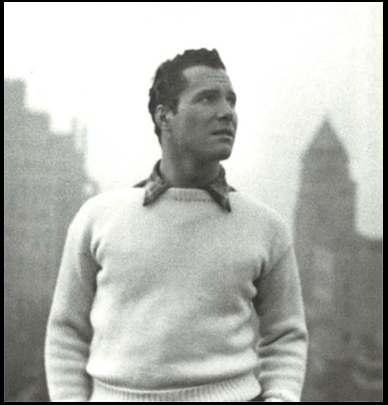

It's unknown when Rydell and Hill met but they certainly knew each other by 1950 as Jerome took this picture of Charles at that time.

Charles Rydell (1950)

Photographer: Jerome Hill (MAC)

("Living the Arts," Jerome Foundation, 2005)

According to Guiles, Warhol first met Rydell through fellow Carnegie Tech alumni, Victor Reilly. Both Reilly and Rydell were on hand when Warhol arrived in New York:

Fred Lawrence Guiles:

One of his [Warhol's] old friends from Carnegie Tech's modern dance group, Victor Reilly, met Andy within hours of his arrival at Penn Station. And actor friend, Charles Rydell, accompanied him, and Andy made no secret of the fact that the thought Rydell was sensational-looking. He was tall, wavy-haired, broad-shoulderd, with a strong resemblance to the young Charlton Heston, except that Rydell's features were much more refined. Within a few years Rydell was in the off-Broadway musical The Threepenny Opera, and in the 1960s he was cast as Hercules in the Broadway musical By Jupiter. (LB49)

Guiles also quotes Rydell as saying, "At Andy's memorial service, I told somebody that I met Andy on his first day in New York and that he was so boring I didn't see him again for ten years. I was just joking..." (LB50)

It's interesting that Guiles says that Reilly was in Carnegie Tech's modern dance group as other biographers have indicated that Warhol was the only male member in the group. When Warhol first moved to New York in 1949, he lived with fellow classmate Philip Pearlstein but by August 1950 he was living with Victor Reilly and other classmates from Carnegie Tech in a house at 74 West 103rd Street. (See "74 West 103rd St.")

According to Guiles, Rydell appeared in a production of Threepenny Opera in 1954 and that Warhol was still involved with the amateur drama group, Theatre 12, at that point.

Fred Lawrence Guiles:

...Kurt Weill and Brecht's The Threepenny Opera was one of off-Broadway's biggest hits at the Theater de Lys on Christopher Street, a short distance from Theater 12. The Brecht-Weill collaboration opened in 1954 while Andy was still involved with the group, and ran for six years. One of his close friends, Charles Rydell, was appearing in it, and it was a "must see" for everyone in town. (LB106)

The meeting of Rydell and Warhol is recounted slightly differently in Popism. Rydell's name first comes up in regard to a screening of Warhol's film Tarzan and Jane Regained, Sort of... in Jerome Hill's suite at the Algonquin Hotel in Manhattan in 1963. Rydell was at the screening and Warhol recalled that he had met him earlier through someone named "Nancy March." The name "Nancy March" could be a pseudonym as she is not mentioned elsewhere in the book or in any Warhol biographies. "Nancy" was sometimes used as slang for a homosexual.

From Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, Popism: The Warhol Sixties (NY: Harcourt Brace, 1980), p. 46:

A young actor by the name of Charles Rydell was at that Tarzan screening. We had a mutual friend named Nancy March who'd introduced us in the pouring rain on my first day in New York years before. Charles has been working in Nedick's then, and I was just off the bus from Pittsburgh, but I hadn't seen him - at least not to talk to - since. However, I'd happened to catch his performance in Lady in the Dark with Kitty Carlisle at the Bucks County Playhouse, and I told him so right away. He thought I was putting him on - he looked at me as if to say, "Oh, come on - nobody saw me in that." He was a very big man with a big temper and a great sense of humour. He could really bellow, and he had the deep full voice to do it right. At the Tarzan screening there was a fat guy named Lester Judson who every couple of minutes would point at the screen and say, "This isn't a movie - it's a piece of shit! You call this a movie?" Finally Charles got fed up and almost blasted him off the chair with "Oh, shut up, Lester! Here you're putting it down and this whole underground thing is just trying to get started!"

I liked Charles and I asked if I could call him to be in a movie of mine. He said sure, any time.

Later, Rydell consented to be in Warhol's film Blow Job, but he thought Warhol was joking when he suggested it and never showed up for the shoot.

Interview magazine

Rydell and Hill became part-owners of Interview magazine in 1970. Bob Colacello had recently been promoted to editor of the magazine and the first issue he edited was devoted to Rita Hayworth. After supervising the printing of the issue and distributing it to places like the lobbies of MoMA lobby, the Anthology Film Archives and shops like Cinemabilia and the Memory Shop, Colacello went to Warhol's office to give him some copies to take to dinner. Warhol invited him to the dinner so that he could meet the "new owners" of Interview.

Bob Colacello:

I went... to give Andy a few copies to take to dinner. "Gee, thanks," he said. "Uh, maybe I should take you to dinner. It's Jerome Hill and Charles Rydell. Uh, they're the new owners of Interview."

The new owners?

"Uh, I mean, they own part of it now. I think."

"But I'm not really dressed for dinner."

"Yes you are. Gee, that's such a pretty striped polo shirt. Did your mother get it for you at Saks?"

"Yes, but don't I need a tie and jacket?"

"Uh, it's at the Algonquin and they uh live there, so you can wear one of their jackets and uh ties." (BC41)

The first issue of Interview magazine that Bob Colacello edited - the Rita Hayworth issue (Vol 1. No. 11) (1970)

Colacello continues with a description of his evening with Hill and Rydell - a dinner that also included Taylor Mead, Sylvia Miles, and Hill's nephew, the photographer Peter Beard.

Bob Colacello:

We finally reached the Algonquin, thank God, and went upstairs to the suite that Jerome Hill, the elderly heir to the Northern Pacific railroad fortune, kept for the times he came into the city from his farm in Bridgehampton. We were greeted by Jerome's long-time best friend, actor Charles Rydell. Before Andy could introduce me, Charles bellowed, "I know who he is! And I've seen his first issue. I hate it. All those Rita Hayworth stills are so goddamn campy. Brigid brought it up to me this afternoon. She was going to stay for dinner until she heard you were coming, Andy." I hadn't met Brigid Berlin yet because she and Andy were fighting then. "Come in, Robert," bellowed Charles, "I don't really hate your first issue. It's just that Brigid was ranting and raving against all the campy faggots and she got me going. Let me introduce you to Jerome. He's the real genius in this room. Not the fruitcake you came in with." Then he bellowed out a giant laugh.

Jerome Hill, I soon learned, was not only part owner of Interview and a patron of the arts but also an artist himself, who painted École de Riviera landscapes at his summer house near Cannes, and directed documentaries about growing up rich in the Middle West. Above all he was a gentleman, simple and kind. He loaned me a jacket and tie, and, even thought the jacket was two sizes too large and the paisley tie clashed with my striped shirt, I began to feel more comfortable in this strange new world. Then I met the rest of Charles and Jerome's Algonquin round table.

First came Taylor Mead, another sometime Superstar who had fallen out with Andy. Like Jerome Hill, he was the scion of a major Middle Western industrial fortune, but a gentleman, simple and kind, he was not. He looked like a Bowery bum and talked like a Village waif. He spent most of dinner staring suspiciously across the table at me.

Then came Sylvia Miles, spouting the box-office figures of Midnight Cowboy, the hit film of the moment, in which she played a hooker with a heart of brass. Andy resented the success of the John Schlesinger film. He said it was a "rip-off" of Flesh, and that Schlesinger wasted the Factory's time for days shooting the party scene and then cutting it to shreds.

"Andy," rasped Sylvia, "I loved Joe Dallesandro in Trash. I was thinking, we should really work together. In fact, I've got a script right here in my bag that would be perfect for the two of us. I'm carrying it around because I just came from a drink with my agent, Billy Barnes - you know Billy, he handles Tennessee - and he wanted to discuss it, and then when I told him I would be dining with you later in the evening he said..."

"Oh, uh, you should talk to Paul," said Andy.

Finally with the third round of cocktails came Jerome Hill's nephew, Peter Beard. With his wife, Minnie Cushing, of the Newport Cushings. And their pet snake, all coiled up in Minnie's large straw bag. They were just back from their honeymoon in Kenya and looked as if they hadn't had time to change their clothes. Peter wasn't even wearing socks, and this was November in New York.

"Aren't they beautiful?" Andy whispered. "Don't you wish you could be that beautiful?"

"Oh, Andy," bellowed Charles, "stop acting like such a goddamn fucking faggot. No wonder Brigid can't stand to be around you anymore."

Andy said Charles was just being nutty, Sylvia said she had a great idea for a movie starring Charles and her, Peter passed around his latest photographs of dead elephants, Minnie patted her snake, Taylor stared suspiciously, and Jerome asked me if I'd like another drink. "Yes, " I said. "A double vodka on the rocks, please."

I don't remember much more about that first dinner party, except that Andy started taking Polaroids of the eager Greek waiter and Charles proposed that we all - including the waiter and the snake - go back to Jerome's suite, whereupon Sylvia announced that she had an early script meeting with a major director and needed me to escort her home. I gave Jerome his jacket back, but he insisted I keep the tie, which I still have, a souvenir of the beginning of a decade of dinner parties in hotels around the world. Somehow I hailed a taxi, dropped Sylvia off on Central Park South - "Tell Paul to call me about the script Andy wants him to read" - and made it home to my furnished room.

At precisely nine the next morning, Andy called. "You were a bit hit with Charles and Jerome, " he said. "Isn't Peter great-looking? And it's great the way he talks so fast. Except I never know what he's talking about. Do you think he has a problem?" Eventually he got to Interview. "It was pretty good," he said. "But maybe Charles was right. Doing just Rita does look too campy. But then Charles is the biggest camp of all, right? So I never know." (BC42-43)

The photographer, Peter Beard, mentioned in the above quote was actually Jerome Hill's cousin, not his nephew, according to a biographical essay published by the Jerome Foundation. (LA10)

Hill and Rydell's involvement with Interview didn't last long. According to Bob Colacello in the chapter of his book, Holy Terror, that covers 1971, Fred Hughes "was secretly negotiating the sale of the Jerome hill and Charles Rydell shares to Peter Brant and Joe Allen, his new best friends - and Andy's new best clients. Peter Brant and Joe Allen were in their twenties and ran their fathers' rapidly expanding newsprint company. Bruno Bischofberger, Andy's new Swiss art dealer, was also part of the complicated transaction, which involved the exchange of paintings, the publication of the Electric Chair prints, tax write-offs - a typical Fred Hughes deal. And Fred's name went on the masthead as editor, above those of Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol." (BC102)