Expanded Cinema? cont.

by Gary Comenas (2014)

page two

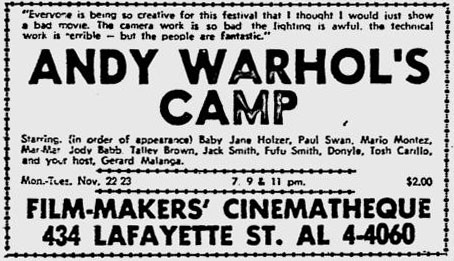

Camp

Andy Warhol's participation in the festival, as noted by David Bourdon on page one, was a screening of Camp on 22-23 November. It was advertised in the 18 November issue of The Village Voice. The wording of the ad and the fact that it was advertised separately might leave one to doubt that the evening was part of the festival, but Warhol was one of the artists that were announced on the first ad for the festival and the original press release. (see page one).

The Village Voice, 18 November 1965, p. 22

There was no mention in the ad of Bourdon's previous description of "split-screen movie projections accompanied by a rock group and the early glimmers of a light show," but it did mention that the evening would be hosted by Gerard Malanga. There was a showing of Warhol's More Milk Yvette the following year at the Cinematheque on 8 February 1966 which featured a split screen and included a performance of The Velvet Underground, but its unknown who the "rock group" was at the screening of Camp the year before (assuming that Bourdon's claim was correct and wasn't confusing the two events.) (CH6-7)

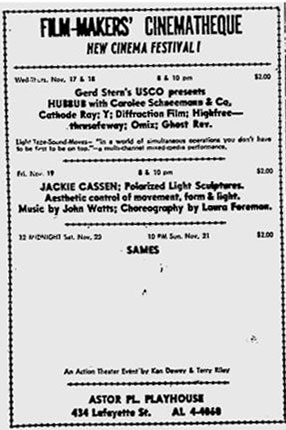

The Camp ad was followed by another one which gave the schedule for the next festival events.

The Village Voice, 18 November 1965, p. 22

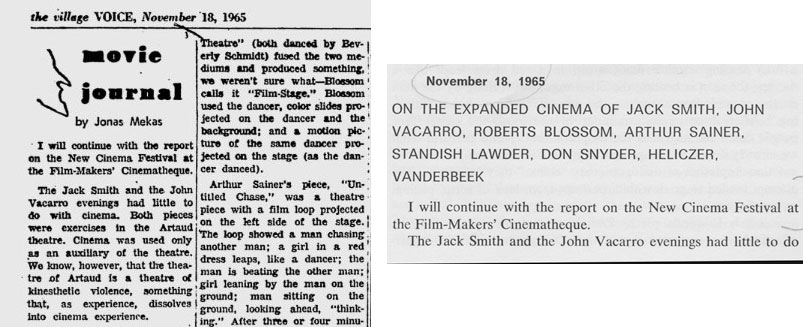

Mekas used the term "expanded cinema" in his column in the same issue of the Voice as the above ad (18 November 1965) but still referred to the festival as "the New Cinema Festival:"

Jonas Mekas (18 November 1965):

I will continue with the report on the New Cinema Festival at the Film-Makers' Cinematheque.

The Jack Smith and John Vacarro evenings had little to do with cinema. Both pieces were exercises in the Artaud theatre. Cinema was used only as an auxiliary of the theatre. We know, however, that the theatre of Artaud is a theatre of kinesthetic violence, something that, as experience, dissolves into cinema experience...

Although the Jack Smith and the Vacarro pieces were presented as part of the New Cinema Festival, they may be - historically speaking - the first successful fusion of the Artaud theories, the happenings and environment experiences, and the traditional theatre (through the spoken word) into a new kind of theatre...

The most dazzling pieces of 'expanded' cinema in the true sense were provided by that old Barnum of cinema, Stan Vanderbeek, in his three motion picture compositions: Movie-Movies... Pastororale: et al... and Feedback No. 1: a Movie Mural...

Piero Heliczer's evening, The Last Rites [see 4 November ad on previous page], was a ceremony, a ritual - really, the most successful (as ritual) of the six rituals presented at the festival. This was not because Heliczer had for his script the New Testament; not because he played a bishop; but because of a certain unfaked directness, immediacy that he produced. Although he was 'acting,' there was something very real about it. Angus McLise's music helped much to sustain this mood... (JM211-14)

All of Jonas Mekas' columns in the Village Voice were published without titles originally but when Mekas later included them in his book, Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema 1959-71, he titled them - adding the words "expanded cinema" to many of the titles. (Mekas' book was published in 1972 - two years after Gene Youngblood's book, Expanded Cinema, was published.) The term "expanded cinema" did appear in the body of at least three of Mekas' columns from 1965 but the term was particularly emphasized in the 1972 titles. In regard to his column on the 18th of November 1965, for instance, he retitled it for his 1972 book, "On the Expanded Cinema of Jack Smith, John Vacarro Roberts Blossom, Arthur Sainer, Standish Lawder, Don Snyder, Heliczer, Vanderbeek." The original 1965 article did not have the "expanded cinema" title. It was simply labelled with the name of Mekas' column "Movie Journal."

Left: Jonas Mekas' original 1965 Village Voice column and (right) how the article was

presented in his 1972 book with the additional title that made reference to "expanded cinema."

In his introduction to his 1972 book, Mekas points out that there may be differences between the columns as they appear in his book and their original appearance in the Village Voice:

Jonas Mekas (Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema, 1959-1971 (New York: Collier Books, 1972), p. viii):

This collection of 'Movie Journals,' this book that you are holding in your hands, represents approximately one third of the columns I did for the Voice since November, 1958. Some of the columns are reproduced in full, others in excerpts. Here and there are slight changes, a word dropped, or syntax improved... In preparing this collection I stuck to the core of my basic preoccupation of the period, which was the independently made film and the related Expanded Cinema, which since has become known as the New American Cinema, and sometimes is also called the underground Cinema. (JMviii)

His last sentence in the above quote is slightly confusing. The "New American Cinema" existed prior to the "Expanded Cinema." It was a phrase used by "The New American Cinema Group" (aka "The Group") to describe the the work of mostly American independent filmmakers. The Group's first statement was included in the Summer 1961 issue of Film Culture magazine which Mekas edited and published. (See: "Jonas Mekas and the Film-Makers' Cinematheque.") The term "Expanded Cinema" came into use several years later and generally referred to cinema that extended beyond the boundaries of the screen or cinema that incorporated new technology or used existent technology as part of a filmic experience. The term had become increasingly popular since the publication of Gene Youngblood's book, Expanded Cinema, published in 1970, not long before Mekas had probably started assembling his columns for their 1972 publication.

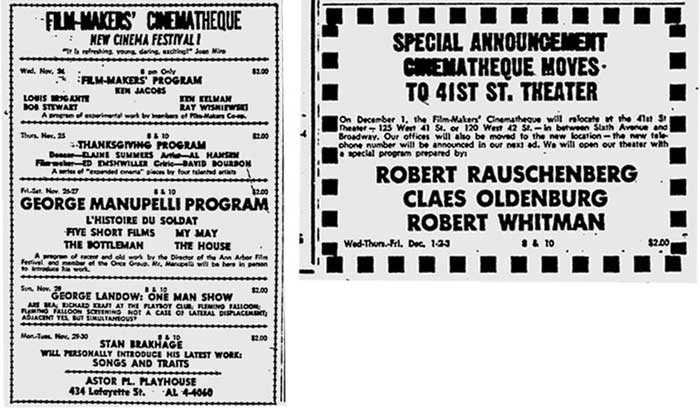

Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman

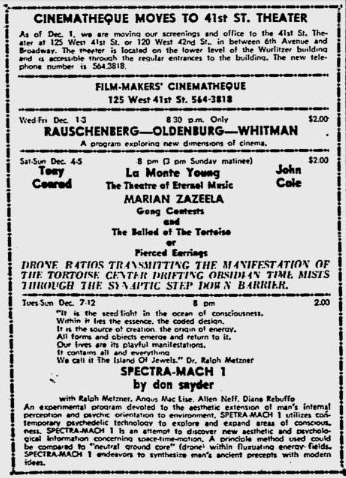

Mekas' 1965 New Cinema Festival 1 schedule was continued in an advertisement in the Voice on 25 November 1965, along with the announcement that the Cinematheque was moving from Lafayette Street to 41st Street on 1 December 1965. The first presentations at the new address were performances by Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman.

Village Voice, 25 November, 1965, p. 20

The next issue of the Voice repeated the news about the move and included the announcement of a La Monte Young performance featuring John Cale and Tony Conrad.

The Village Voice, 2 December 1965, p. 22

Note that the ad is no longer headed with "New Cinema Festival 1." In his 9 December column Mekas proclaimed, "With an evening of La Monte Young's heavenly music, the first New Cinema Festival has come to its conclusion." (JM218) But he repeated the Rauschenberg, Oldenburg and Whitman performances on the 16-17th of December and noted in his column on the 23rd that their performances were "the closing program of the New Cinema 1 Festival at the Cinematheque." (JM220)

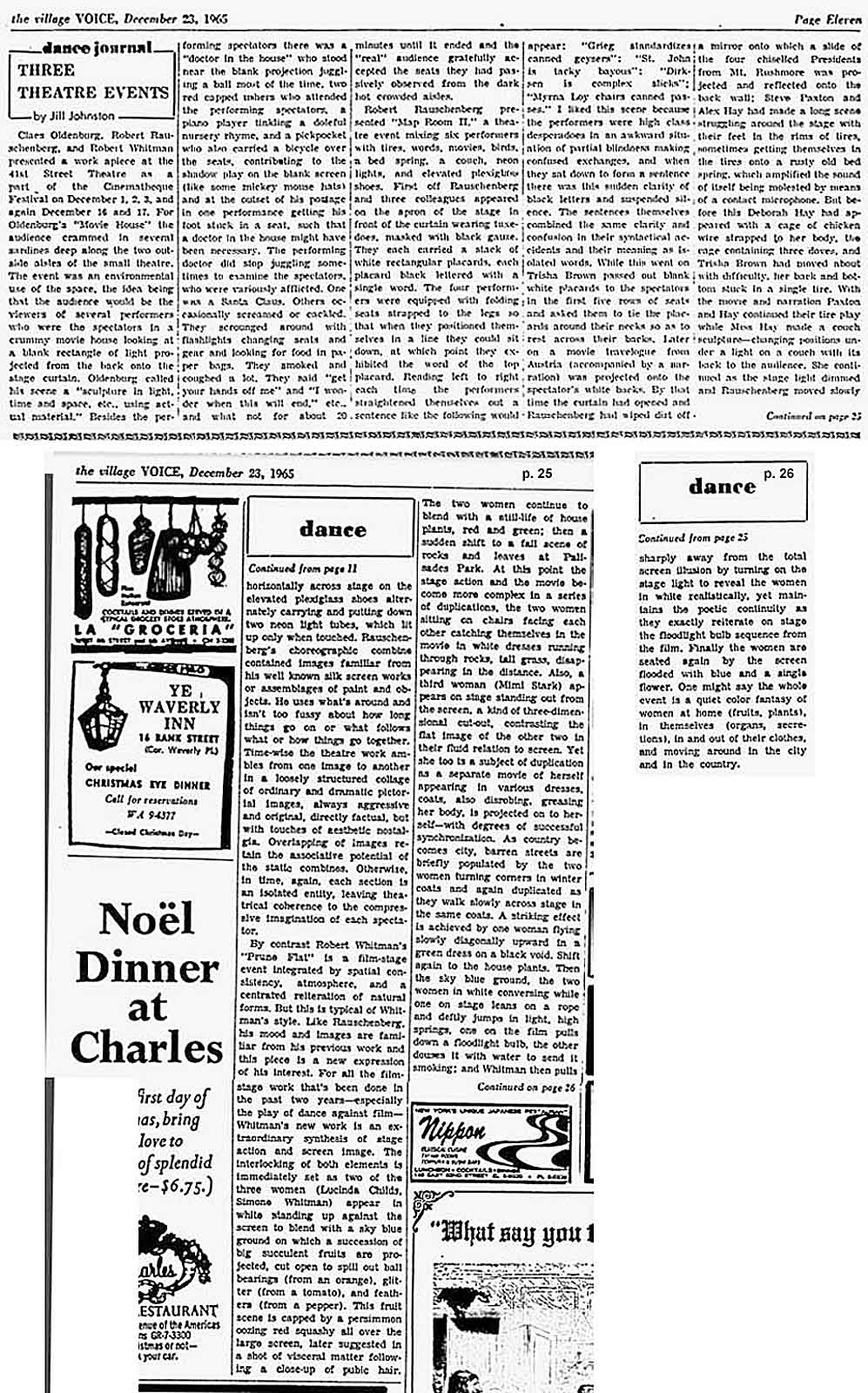

Again, the December 23rd column was originally untitled but when he included it in his 1972 Movie Journal book, Mekas added the title, "More on Expanded Cinema: Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Whitman," although the term "expanded cinema" did not actually appear in the article and he referred to the festival as the "New Cinema Festival 1."

Jonas Mekas (23 December 1965):

Last column I did not have time to report on the closing program of the New Cinema Festival I at the Cinematheque, but I should mention it now since it was one of the most successful programs of the festival (It was repeated last week.) Each of the artists - Oldenburg, Rauschenberg, Whitman - came with beautifully conceived and executed pieces. Oldenburg's Moviehouse piece was performed in the seats of the theatre, while the audience stood in the aisles. A group of performers sat in the seats watching a movie... they moved from place to place, restless, as people do, smoking a lot, carrying packages and bundles and shopping bags; a man tried to drag a bicycle across the seats - a colorful medley of people from various walks of life...

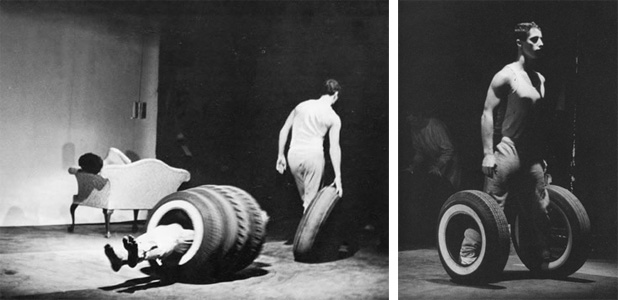

Robert Rauschenberg presented a motion-dance-objects piece, Map Room II... Robert Whitman's show combined live action with the filmed image." (JM220-221)

Two images from Map Room II (1965)

L: Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Robert Rauschenberg/R: Steve Paxton

Photos: Peter Moore

The importance of the pieces, and the artists who presented them, was reflected in the fact that both John Cage and Marcel Duchamp attended at least one of the Rauschenberg, Oldenburg and Whitman performances. (RK55/56)

Film or projections, in one form or another, played a part in most, if not all events presented at the festival. In regard to Rauschenberg's Map Room II, for instance, the dancer Trisha Brown handed out large white cards to the audience to attach to their backs and, as Rauschenberg described it, "Part of the audience would later become a movie screen." (RK89) The Whitman piece involved the projection of filmed images onto human beings. At one point a filmed image of a knife cutting through fruit was projected onto live women. (RK225) Whitman noted about the piece, "I suggested in the piece itself that it was about movies. I think that's very clear. It opens with a picture of a movie-projector. That's the first image. I used it as a reference point - to tell people that this is a movie." (RK224)

The Oldenburg piece, referred to by Mekas as "Moviehouse" and as "Movie House" by Jill Johnston below, but listed as "Moveyhouse" in later listings of Oldenburg's pieces featured both Claes and Pat Oldenburg in the cast, as well as Dominic Capobianco, Lette Eisenhauer, Jo Eno, John Jones, Fred Mueller, Ellen Sellenraad and Johann Sellenraad in the cast, with Liz Stevens on piano. Oldenburg was particularly inspired by the Cinematheque's auditorium because it was "special" and was being used as a real movie house. When he was asked to perform Moveyhouse in a venue in Hartford, he rejected the offer because the Hartford venue was too "neutral."

Claes Oldenburg:

That (the 41st Street Cinematheque) was a very special auditorium. This is the room in the Wurlitzer building, where the Wurlitzers used to promote the sales of their violins and things by giving recitals. My friend, Rudy Wurlitzer, can remember having a recital in there. That's why its walls are all done up with scenes of Europe, pillars along the side, and all that kind of stuff gives it a certain identity. Also, right now, as the Forty-first Street Theatre, it is a moviehouse, you know, and that fact gives it additional character.

I didn't accept an invitation to do Moviehouse in Hartford, because I knew the auditorium there was so neutral that the piece would have lost all its effect - the backlighting on the landscape, and the pillars and so on. The [Wurlitzer] auditorium is something like the late Paramount; there's enough to look at, if you don't want to look at the screen or the stage. (RK143)

Jill Johnston reviewed the Oldenberg, Rauschenberg and Whitman pieces in the December 23rd issue of the Village Voice, describing them with a fair amount of detail:

In her article she refers to the festival not as the Expanded Cinema Festival but as the "Cinematheque Festival" and does not refer to the pieces as "expanded cinema" but rather as, in the case of Whitman at least, "film-stage work."

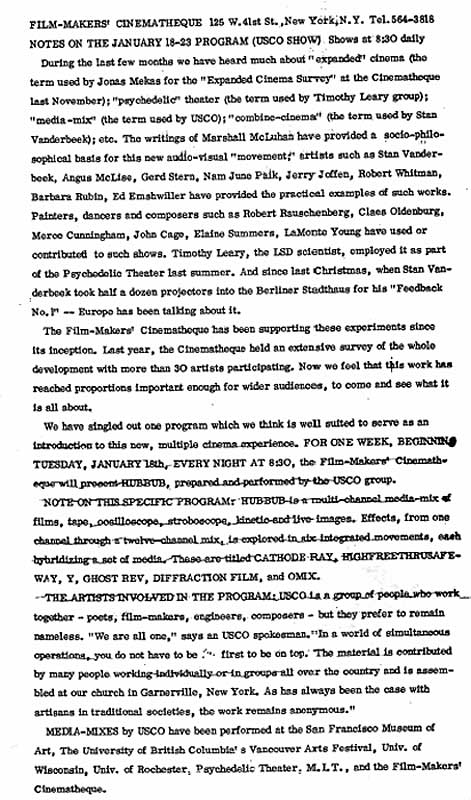

USCO

After the festival ended, Mekas presented another multimedia event by USCO the following month. The info sheet for the event referred to the previous festival as the "Expanded Cinema Survey:"

Mekas also used the term "expanded cinema" in the Village Voice ad for the USCO performance referred to above. But, again, this was after the New Cinema I festival had already ended.

Village Voice ad, 13 January 1966

Mekas' festival, then, was referred to by a number of different names. In the USCO info. sheet above from 1966 it was referred to in the past as the "Expanded Cinema Survey." When Mekas first announced the festival in his 3 June 1965 column for The Village Voice, he announced a "survey of the various new uses of cinema" in which "leading artists of these new uses of cinema (expanded cinema) will take part." One press release closer to the opening of the survey on November 1st, was headed "Festival of Expanded Cinema." Another press release went out, probably around the same time, which referred to the festival as the "New Cinema Festival I." The festival was advertised in the Voice as the "New Cinema Festival I". Later, however, when reminiscing about the festival, people like the playwright Richard Foreman would remember it as the Expanded Cinema Festival. Authors writing historically about the festival also referred to it as the Expanded Cinema Festival. But at the time that it took place, Jonas Mekas, himself, referred to it as the New Cinema Festival in his Village Voice columns. He may have introduced the term "expanded cinema" by using it in at least three of his columns from 1965, but because the the festival was advertised as the New Cinema Festival I and because Mekas referred to it by that name in his Village Voice columns at the time, it does appear that the title of the festival was the New Cinema Festival I. There was no festival officially named the Expanded Cinema Festival. The events that took place at Mekas' festival may have been examples of expanded cinema but the festival, itself, was named the New Cinema Festival I.