Jonas Mekas and the Film-Makers' Cinematheque

Gary Comenas (2014)

See also: Expanded Cinema?

page one

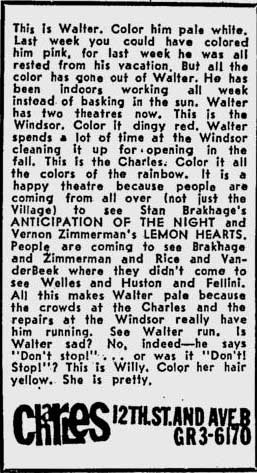

Many film writers refer to screenings at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque without identifying the actual venue. This can be confusing because the Cinematheque often changed location and sometimes the venues used were advertised under different names. The 41st St. Theater became the 42nd St. Cinema which became the New Cinema Playhouse. The New Bowery was the same venue as the American Theatre for Poets (when it was subleased by Diane di Prima) as well as later being called The Bridge. Mekas used the term "Cinematheque" almost like a type of branding to advertise screenings at different venues over time. Sometimes writers incorrectly refer to Mekas' pre-1964 screenings at venues like the Charles Theatre as Cinematheque screenings when the Cinematheque was not started until late 1964, as announced in the pages of the Village Voice. Many of Mekas' screenings (both pre and post Cinematheque) were advertised in the Voice for which Mekas also wrote a column titled "Movie Journal" beginning with the 12 November 1958 issue. At the time he started writing for the Voice, he was already the publisher and editor of Film Culture magazine which began publication in 1955. In 1960 he helped to form the New American Cinema Group (or simply "The Group") which promoted American experimental film as the "New American Cinema." A year or so after The Group was formed, Mekas established the Film-Makers' Co-op which, according to film writer David E. James, "came into being on 18 January 1962." As the main film columnist for The Village Voice Mekas was able to review the films he screened without necessarily mentioning that he was behind the screenings. As time progressed, however, it became clear that he was often behind the screenings he was reviewing, particularly when he ended up in jail for showing Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures.

Jonas Mekas

Mekas arrived in the U.S. as a Lithuanian refuge after World War II, having spent a considerable time as a displaced person in Germany. As explained by Mekas, Displaced Person camps "were established by the Allied Forces to accommodate 8,000,000 forced laborers, survivors of KZ camps, war prisoners and political refugees (mainly anti-Soviet) liberated by the Allies. Within a year after the German surrender some 6,000,000 of them returned of their own will or were pressed into returning (as some of the Soviet war prisoners were) to their respective counties. The other 2,000,000, among them Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians, refused, mainly for political reasons, to return to their homelands, now occupied by the Soviet Union. The United Nations created a special International Refugee Organization (I.R.O.) to take care of the political refugees. Although there were no restrictions on the movements of the refugees, every refugee had to belong to a D.P. camp in order to received food and lodging, and to received assistance with emigration." (JMN68)

In Lithuania Mekas' main interests had been poetry and literature rather than film. He was forced to leave the country because of his involvement in "anti-German activities" at a time when Lithuania was occupied by Germany.

Jonas Mekas (I Had Nowhere to Go, 1991):

"When I left my home, when I left my small village... on a trip that eventually landed me in New York, I was 22 years old. I was a young man of some reputation. For over a year I had worked as editor-in-chief of a provincial weekly paper. I had worked as the technical editor of a national semi-literary weekly for another year. I had published my first poems and had created a scandal in the literary 'world' of Lithuania with what I would now call vicious and foolish attacks on some of the writers and poets of the generation that preceded me...

During the years 1943-1944, during which time Lithuania was under German occupation, I got involved, like many other people my age, in various anti-German activities. I joined a small underground group which, amongst other things, was publishing a weekly underground bulletin. This consisted mostly of news transcribed from BBC broadcasts. It informed people about German activities in Lithuania and other occupied countries. It was one of several such bulletins published by underground groups during the German occupation. The German secret police did everything to uncover the publishers. The only clues they had were the type-faces of the typewriters used to type up the bulletins. The way I come into this is that I was assigned to do the typing. Once a week information materials were delivered to me, and I prepared the pages. I lived at that time in the attic of my uncle's house in Biržai. My uncle was a Protestant pastor and the house in which he lived belonged to the church and stood on a lake shore, quite remote from other houses. There was a barn there too, and a huge stack of firewood for heating the house in winter. I used to hide the typewriter in the firewood stack. I felt it was quite safe there. But I was wrong. One night I went to pick it up, to do the typing - but the typewriter was gone! I had no other explanation but that a thief was snooping around, found the typewriter and stole it. I reported this to my underground friends and we all agreed that the best thing for me was to disappear. We couldn't take chances on the thief selling the typewriter and Germans discovering the type-face they had been desperately searching for. It was clear to us, that in such a case, the thief would reveal the source of the typewriter." (JMN1,18)

Mekas and his brother, Adolfas, attempted to make their way to Denmark, planning to then travel from Denmark to Sweden, but by 29 May 1945 were in a Displaced Persons camp in Germany - Camp Mürwick (or Meierwik). (JMN196) It was while they were staying in a D.P. camp that the brothers became interested in film:

Jonas Mekas:

"The first time I really got interested [in film] was after the war in 1945, in Wiesbaden in a displaced persons camp where the American army showed Tarzan movies and, you know, all those movies that they show to the army. But one evening I saw The Treasure of Sierra Madre (John Huston, 1948), and I thought that there was something to it. Especially I remember liking the ending, and the desert, the sense of something crawling. Visually it was interesting. Then I saw another movie, I think it was by Zinnemann, made in Switzerland I think, The Search (Fred Zinneman, 1948), about displaced persons, made immediately after the war. And I saw it with my brother and we got very angry about how little understanding of the real situation there was in this film, about what it means to be displace. We got angry and we started writing scripts. That's when we decided to make our own films. That's where it begins. But it wasn't until we came to new York that we actually began making films. You know, in a displaced persons camp, there is no way of getting money, a camera or film or anything. And when we arrived in New York, we had not really seen anything really decent. So it wasn't until late in '49 when we arrived in New York that we began going to MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) and seeing all the varieties of cinema. We rented a Bolex, the next week practically after we arrived, and started fooling around. That was the beginning." (BLFS)

Trailer for The Search (1948) starring a "handsome new American star Montgomery Clift."

Mekas and his brother arrived in the U.S. as refugees on 29 October 1949. In addition to shooting his own footage, he attended screenings in New York. In the early fifties he met Louis Brigante which apparently led to him holding the first screenings of his own. Although many film writers have written about the screenings Mekas held at the Charles Theatre in 1961 as his first screenings, Mekas has stated that he actually started showing films in 1953.

Jonas Mekas:

"In 1953, I started the first screenings of what was called at that time Experimental Films. I showed the Whitney Brothers, Gregory Markopoulos, Kenneth Anger. I started my own screenings at Gallery East which was on Avenue A and 1st Street... Also in 1953, a woman by the name of Dorothy Brown had weekend screenings in her loft on Ludlow Street. I helped her. Around the same time, Gideon Bachmann was running the Film Study Group, which I joined. I helped to write notes. Once a week or so, or every two weeks, we had screenings, usually with filmmakers present. And on it goes. And if you were clever enough, which of course I was, I also used to sneak into the New York University. As part of the film department, George Amberg - who began as a ballet critic, and wrote a very important book on ballet - was holding screenings of the avant-garde films for students, but you could sneak in. And he had filmmakers present. That's where I met Gregory Markopoulos... You could also sneak into the New School for Social Research where Arthur Knight had classes on the independent, avant-garde, experimental film. With filmmakers also usually present. So, as you can see, there was a lot going on. Actually, the second evening after arriving in New York, I was already at the movies. I saw The Fall of the House of Usher (Jean Epstein, 1928) and The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920) on, I think, 16th Street or somewhere, at the New York Film Society run by Rudolf Arnheim." (BLFS)

In January 1955 the first issue of Film Culture came out with Mekas and his brother on the editorial board which also included George Fenin, Louis Brigante and Edouard de Laurot.

David E. James (To Free the Cinema: Jonas Mekas &The New York Underground, 1992):

"While it was oriented toward Europe, from the beginning Film Culture gave sympathetic critical attention to American film, and eventually seminal work on Hollywood appeared there, most notably Andrew Sarris's 'Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962' and 'The American Cinema' (appearing in 1963 in nos. 27 and 28 respectively). This tolerance did not extend to the avant-garde; an early issue contained Mekas's immediately notorious attack, 'The Experimental Film in America,' in which he lambasted the 'adolescent character,' a putative 'conspiracy of homosexuality,' the 'lack of creative inspiration,' and the 'technical crudity and thematic narrowness' variously to be found in the work of young filmmakers including Stan Brakhage, Gregory Markopoulos, Curtis Harrington,and Kenneth Anger. Mekas himself later termed this a 'Saint-Augustine-before-the conversion piece,' and the religious metaphor is entirely appropriated, for within a few years he was the fiercest advocate of what he had come to see as a new and distinctively American film culture, and an entirely new sense of its political significance." (DJ7-8)

Despite apparently having presented their work at the Gallery East in 1953, Mekas "lambasted" the films of Gregory Markopoulos and Kenneth Anger in an early issue of Film Culture.

The New American Cinema Group

The Summer 1961 issue of Film Culture included "The First Statement of The New American Cinema Group" which included Mekas on the executive board (as well as Warhol's friend, Emile de Antonio.) The statement was headlined "THE GROUP."

"THE GROUP

On September 28th, 1960, a group of twenty-three independent film-makers, gathered by invitation of Lewis Allen, stage and film producer, and Jonas Mekas, met at 165 West 46th Street (Producers Theater) and, by unanimous vote, bound themselves into a free open organization of the new American cinema: The Group." (PA79)

The temporary executive board that was elected at the meeting consisted of Shirley Clarke, Emile de Antonio, Edward Bland, Jonas Mekas, and Lewis Allen. (PA79) The "FIRST STATEMENT" of the The Group included a scathing appraisal of mainstream cinema at the time which, they noted, was "running out a breath:"

"In the course of the past three years we have been witnessing the spontaneous growth of a new generation of film-makers - the Free Cinema in England, the Nouvelle Vague in France, the young movements in Poland, Italy, and Russia, and, in this country, the work of Lionel Rogosin, John Cassavetes, Alfred Leslie, Robert Frank, Edward Bland, Bert Stern, and the Sanders brothers.

The official cinema all over the world is running out of breath. It is morally corrupt, aesthetically obsolete, thematically superficial, temperamentally boring. Even the seemingly worthwhile films, those that lay claim to high moral and aesthetic standards and have been accepted as such by critics and the public alike, reveal the decay of the Product Film. The very slickness of their execution has become a perversion covering the falsity of their themes, their lack of sensitivity, they lack of style.

If the New American Cinema has until now been an unconscious and sporadic manifestion, we feel the time has come to join together. There are many of us - the movement is reaching significant propositions - and we know what needs to be destroyed and what we stand for..." (PA80)

They also outlined 9 principles of The Group, which included a rejection of the "interferences of producers, distributors and investors until our work is ready to be projected on the screen;" a rejection of censorship, a "reorganization of film investing methods;" low budgets; a rejection of the "present distribution-exhibition policies;" the establishment of "our own cooperative distribution center;" an East Coast film festival to serve "as a meeting place for the New Cinema from all over the world;" lower union rates for low budget films; and the building up of a fund from a percentage of film profits to "help our members finish films or stand as a guarantor for the laboratories."

Two of these principles are of particular interest - the establishment of a cooperative distribution center and an East Cost film festival of New Cinema. Initially Emile de Antonio was put in charge of "cooperative" distribution, with several cinemas pledging to show the films of The Group - The New Yorker Theater, the Bleecker Street Cinema, and the Art Overborook Theater. De Antonio left The Group within the year however and Mekas founded the Film-Makers' Co-op.

The Film-Makers' Co-op

According to David E. James, the Co-op "came into being on 18 January 1962."

David E. James:

"The Film-Makers' Cooperative came into being on 18 January 1962. Unlike previous attempts to organize an independent film distribution center (the Independent Film Makers Association and Cinema 16), the Co-op was nonexclusive, nondiscriminatory, and governed by the filmmakers themselves. It accepted all films submitted to it, and an no pint in its administrative procedures were aesthetic or other qualitative judgments admitted... All the rental fees were to be returned to the filmmakers except the 25 percent retained to cover working costs and the salaries of the paid staff." (DJ10)

Village Voice ad for the Filmmaker's Coop at 414 Park Ave. South (14 May 1964, p. 15)

Jonas Mekas:

"I do not remember, strange as it may seem, but I could put it this way: In 1962, '63, '64, Film Makers' Cooperative was located at 414 Park Avenue South. It was much going, those years. It was a very busy period in New York in the Independent Film area, and the Co-Operative was the meeting ground for, ah, during that period, where the filmmakers stopped by during the day. During the evening, I was living there in the back of the Co-Op space. I gave the front of my space to the Co-Op - the front part was the Co-Op proper during the day. In the evening, it was a sort of night co-op, and during the evenings or afternoons, whenever a filmmaker felt that he wanted to show films to a friend or some[one], he could come in and screen. There was always projectors set up. And in the evenings, practically every evening, there was some little screenings... It was only that filmmakers knew and friends knew that, and this increased when we seemed to have at some films problems, censorship-wise, with public screenings. So, those films were usually screened by filmmakers and their friends at the Co-Operative." (PS415)

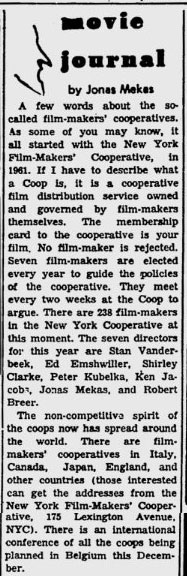

Mekas described the goals of the Co-op in his column in 1967 in which he gave 1961 as a start date for the Co-op:

Jonas Mekas, "Movie Journal," The Village Voice, 23 November 1967, p. 30

The Charles Theatre

According to David E. James, Mekas first presented "weekend midnight programs at the Charles Theater on Avenue B and East Twelfth Street in 1961." In his chronology, "Showcases I Ran in the Sixties," published in To Free the Cinema (edited by James). Mekas also begins his screenings with the ones at the Charles. He doesn't mention the 1953 Gallery East screenings:

"1. Open House screenings at Charles Theater, Avenue B and East Twelfth Street, 1961-1963." (DJ322)

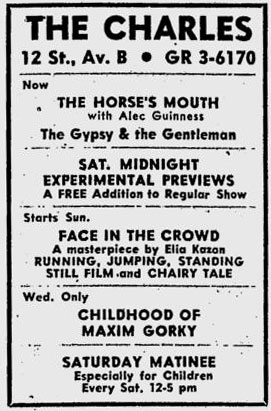

Mekas doesn't specify that the "Open House" screenings were midnight screenings. The Village Voice ads for the Charles show that filmmakers were invited to bring their work to screenings or festivals that weren't at midnight and that midnight screenings were often devoted to one filmmaker.

The weekend midnight screenings were not publicised as Co-op events and Mekas did not mention them in his Village Voice as Co-op events. In fact, he didn't mention that he had anything to do with them. Because of this, it's difficult to know exactly what his input was or when exactly it started. In his 5 October 1961 column for instance, he announces "The Charles Theatre, 12th Street and Avenue B, is open again, with a series of selected revivals. The new owners - Walter Langsford and Edwin Stein, Jr., want it also to be known that the theatre is open for any adventurous 16-mm screenings, experimental films, etc. if anybody has anything. So let's do something about it."(JMV13) Although film writers would later characterise Mekas' screenings at the Charles as a sort of "bring your own film" events, here we have Mekas presenting the idea as the idea of the new owners rather than himself. The first midnight screenings at the Charles were advertised in November 1961, not long after Mekas' column informing his readers that the owners of the venue were looking for experimental films. Most of the midnight screenings focused on the work of a single director. The first ad mentioning a midnight screening was in the 2 November 1961 issue of the Voice for a midnight screening of films by Lewis Jacobs, with Jacobs present.

Sometimes the ads would only promise a "sneak preview" for a midnight screening such as the ad in the 16 November issue. On the 23rd of November, an ad appeared announcing "midnight experimental previews" which were a "FREE addition to Regular Show." Again, it's difficult to know whether Mekas actually had anything to do with these midnight screenings or whether they were due to the efforts of the cinema owners, Langsford and Stein, Jr.

Village Voice ad, 23 November 1961, p. 13

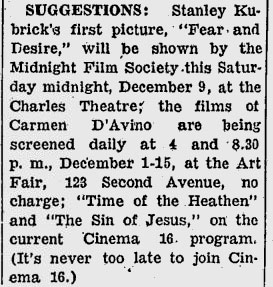

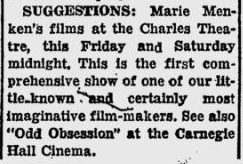

On the 7th of December there was only a "Special Sneak Preview" promised for Friday and Saturday night. In the "suggestions" section of his Village Voice column in the December 7th issue Mekas mentions a group called "the Midnight Film Society" at the Charles Theatre although he doesn't mention if he's involved with the group. (The "Suggestions" section does not appear in the collection of his columns that was published as Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema 1959-1971, but it did appear in the original columns in the Voice.)

"Suggestions" section of Jonas Mekas' "Movie Journal" column in the Village Voice - 7 December 1961, p. 14

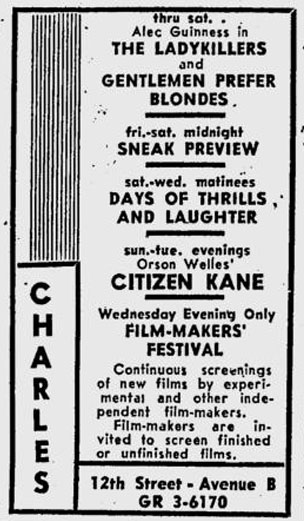

The midnight event advertised the following week at the the Charles was the appearance of Vittorio de Seta. (Village Voice, 14 December 1961, p. 14). The first advertisement inviting filmmakers to bring their films was in the 21 December issue, although it wasn't advertised as a midnight screening:

Village Voice ad 21 December 1961, p. 13

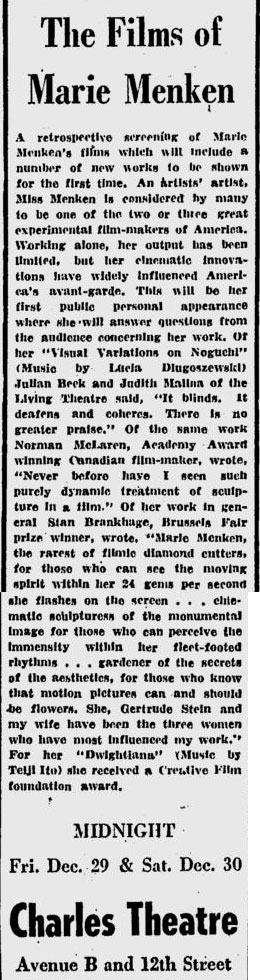

The following week's issue contained a large ad for a Marie Menken "retrospective." It's likely that Mekas had something to do with that evening as he championed Menken's films and it was a midnight screening, although not an "open house" screening.

Village Voice ad, 28 December 1961, p. 11

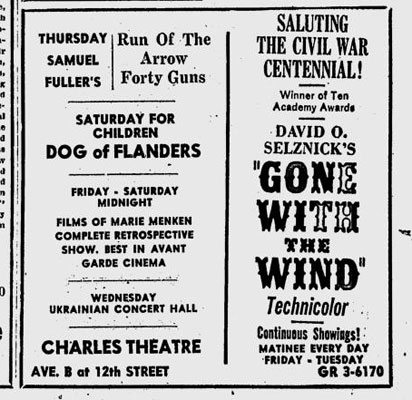

This was in addition to the usual ad for the Charles that appeared in the same issue:

Village Voice ad, 28 December 1961, p. 11

Mekas also recommended the Marie Menken evenings in his Village Voice column in the same issue, but did not say he had anything to do with the screenings:

Jonas Mekas, "Movie Journal" column in the Village Voice, 28 December 1961, p. 12

He followed it up in his 4 January 1962 column with a glowing review of the screening and complaints about the fact that none of the mainstream film critics had attended the screening, apart from Archer Winsten, the reviewer for the New York Post. In his column Mekas does not claim to have had anything to do with the retrospective.

Jonas Mekas:

"The Marie Menken retrospective last week at the Charles Theatre was an important event for all those who care about cinema. I didn't see any of the daily or weekly film critics at the screening; I never see them at any important screening of experimental or poetic works. Archer Winsten, the only critic who came, walked out on Menken after the first two films. The pleasure was left entirely to the audience. The audience is more ready to learn and to explore the unknown than our critics." (JM46)

Marie Menken was one of the filmmakers whose work Mekas praised in his column. Others included Stan Brakhage and Robert Breer. In his 15 March 1962 column, for instance, he praised the work of Brakhage, Menken and Breer over Alain Renais' Last Year at Marienbad. At the time, Mekas thought that Marienbad's "forced intellectualism" was "sick."

Jonas Mekas (The Village Voice, 15 March 1962, p. 13-14):

"Alain Resnais' Last Year at Marienbad is many things. But it is neither a great nor a revolutionary film... For the critics and movie-goers not familiar with the experimental cinema "Marienbad" is the "furthest out" cinema. This shows how little our critics know about what is going on in modern cinema. Had they known Maya Deren's Ritual in Transfigured Time or Meshes of the Afternoon - both made 15 years ago - they would have found little that is revolutionary in Marienbad...

'Who is further out than Resnais?' you will ask. I have a surprise: Stanley Brakhage, Marie Menken, Robert Breer. In Brakhage's films (Anticipation of the Night, The Dead, Prelude) we find not only a more subtle cinematic form but also a more advanced cinematic technique. When you watch Anticipation or Menken's Arabesque, you can hear Robbe-Grillet's lines: 'I walk again through these corridors, through these gardens...'

I can see the historical importance of Marienbad as a forerunner of a commercial experimental film... Renais breaks away from the realist tradition, goes into the subconscious. And that is his greatest contribution to the contemporary dramatic film. The next step is the experimental poetic cinema.

As it is now, I still prefer the pure experimental poets like Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Marie Menken, Robert Breer to the commercial-experimental cinema of Renais. Their work makes me see the world and myself in a new way, and the beauty of it sends me into ecstasy. This is modern cinema and it is a cinema that is human in the most essential way. Marienbad, in comparison, is a frozen, pretentious ornament, full of postures, declamations. Its forced intellectualism is sick."

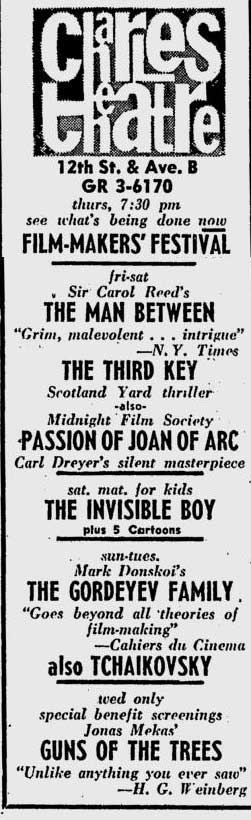

During the previous month, in February 1962, the Charles held a "Film-Makers' Festival" but it's not clear to what extent Mekas played a part in this. It was not a midnight screening - it was on a Thursday at 7:30 pm. The same ad announces the "Midnight Film Society's" screening of Passion of Joan of Arc on Fri-Sat and a Wednesday screening of Mekas' own film, Guns of the Trees - apparently a "special benefit" screening although it doesn't indicate on the ad what it benefited:

Village Voice ad, 8 February 1962

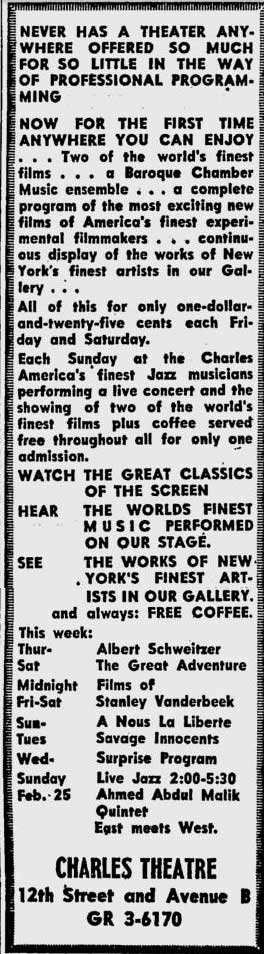

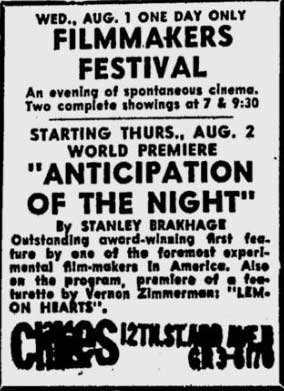

Two weeks later, in the February 22nd issue, the Charles ad gave a general overview of the cinema, promising "a Baroque Chamber Music ensemble," jazz musicians and "a complete program of the most exciting new films of America's finest experimental filmmakers" - not to mention "free coffee." Midnight films of Stanley Vanderbeek were scheduled.

Village Voice ad 22 February 1962

Other midnight screenings during the first three months of 1962 included Rene Clair's I Married a Witch (5-6 January); the films of Nicholas Webster (19-20 January); films of Rudy Burckhardt (26-27 January); films of Joseph Marzano described as "most promising new film-maker" (2-3 February 1962); two "rare silent classics" - The Slums of Berlin (1925) and Le Brasier Ardent (1923) on 16-17 Feb; films of H.G. Weinberg advertised as "a noted critic's fascinating experiment films - among the earliest in the U.S. along with an unidentified film by Sergei Eisentstein (16-17 March); films by San Franciscan Larry Jordan with The Bridge by Vido and Fortune's Fool by Emil Jennings (23-24 March); a retrospective of films by Francis Lee (30-31 March).

In April a Shirley Clarke retrospective was was announced. Clarke, as noted earlier, was a a founding member of The Group and would also later be involved in the Film-Makers' Distribution Center with Mekas.

Village Voice ad 5 April 1962

Although Mekas would, later in the year, identify some of the independent filmmakers who were "waging the real revolution of new cinematic forms and content," as Ron Rice, Stan Brakhage, Marie Menken, Breer and Leacock (JM69), most of the midnight screenings during 1962 had nothing to do with these filmmakers. Screenings for the first half of the year included James Broughton (13-14 April); three films by Alain Renais (25-26 May); Norman McLaren, Slavko Vorkapich and Weegee (8-9 June); and a James Davis retrospective (15-16 June). But who programmed these midnight screenings? Mekas or the owners of the cinema, Langsford and Stein? Mekas continued to write about the screenings as though he had nothing to do with them. Nor did he claim responsibility for the bring-your-own-film Filmmaker's Festivals held at the Charles which, in any case, did not take place at midnight.

Village Voice ad, 26 April 1962

According to the ad for the "Eighth Filmmakers Festival" the bring-your-own-film festival at the Charles was presented by the cinema's owners, Langsford and Stein:

Village Voice ad 28 June 1962, p. 15

The bring-your-own-film festivals were apparently so successful that they extended the program, leaving it open ended. According to the announcement in the Voice the Festival would run "as long as filmmakers submit film." Although this sounds like Mekas' open screenings, neither he nor the Co-op were mentioned in the ad and the screenings did not occur at midnight.

Village Voice ad 5 July 1962

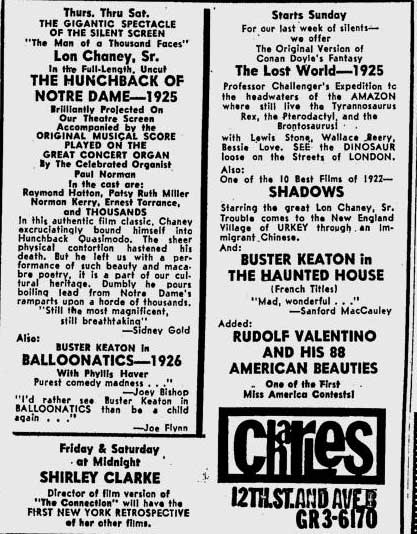

The following week's issue included the announcement of the "World Premiere" of The Flower Thief starring Taylor Mead who was a particular favourite of Mekas (and later of Warhol's).

Village Voice ad, 12 July 1962

Mekas reviewed the screening in the following week's issue (July 19th), again not suggesting that he had anything to do with it although he did mention that he had seen a few versions of the film - despite the fact that the Charles' screening was billed as the "world premiere."

Jonas Mekas (The Village Voice, 19 July 1962):

"Taylor Mead of The Flower Thief (directed by Ron Rice; at the Charles Theatre) is the happy innocent, the unspoiled idiot. He has a beautiful flower soul. He will go to heaven like all children do... The idiot (and the beat) is above (or under) our daily business, money, morality. It is bad, it is pretty bad when we have to learn from the idiot, but that is exactly where we are today. All wise men have gone mad.

That's why The Flower Thief is one of the most original creations in the recent cinema (or any other art, for that matter). That is why to me it is a much more beautiful movie than Marienbad...

I have seen the film in three different versions, a two-hour-long version, a forty-five minute version, and now a seventy-minute version. It always works, no matter how long or how short it is." (JM64-65)

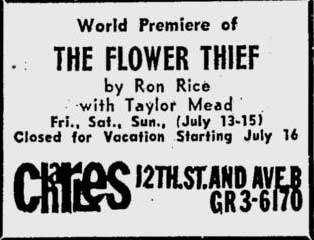

The August Filmmakers Festival took place at 7 and 9:30 pm on August 1st, with another "world premiere" taking place on August 2nd - Stan Brakhage's Anticipation of the Night.

Village Voice ad, 2 August 1962

Amos Vogel of Cinema 16, a members-only film society that had started screening experimental films in the late 1940s, had refused to show Brakhage's film and Mekas had shown the film instead. Brakhage was interviewed about the situation with Vogel and Mekas by Scott MacDonald in 1996:

From "Conversation with Stan Brakhage, 11/30/96" in Cinema 16: Documents Toward a History of the Film Society, 2002):

Scott McDonald: I understand that there was a break between you and Amos Vogel because he would not show Anticipation of the Night (1958) at Cinema 16. Is that true? What was your experience with Cinema 16?

Stan Brakhage: Well, that's true about Amos and Anticipation... His view was that the film would destroy my reputation. I didn't see that I was having any kind of reputation anyway... But the break with Amos wasn't about his refusal to show or distribute Anticipation. There were other films that Amos refused to show or distribute, like Marie Menken's new work; and I told Amos, 'Until you distribute Marie Menken's new work and Anticipation of the Night, I won't give you any of my new work.' There were other films he wanted. So that was the break that finally led to Jane and I advertising that we would distribute films, and that we had an agreement with Bruce Conner and other people we knew about, to distribute from our home in the mountains in Colorado.

At that point, I arrived in New York to begin showing some of my work that Amos was distributing and some work by other people, and at that precise moment, Jonas and Adolfas were deciding to create Film-makers' Cooperative. So we more or less came to an agreement to pool our resources and that's how the New York Co-op began. Jonas and Adolfas were in a better position to do distribution than Jane and I were: they were in New York and they had backing of some kind or other - enough support for the moment, and eventually they also came to have the support of Jerome Hill. Or perhaps Jerome was already involved. So I just became part of their efforts.

Then gradually - and I think to Amos's bitterness - they pushed him out and occupied the Cinema 16 offices. (CS299-300)

The Charles ad in the following week's issue of the Voice announced the opening of another venue. It mentions Anticipation of the Night but doesn't mention Mekas.

Village Voice ad, 9 August 1962

In September, Andrew Sarris substituted for Mekas as the author of the "Movie Journal" column in the Voice. He wrote a scathing criticism of the Filmmakers' Festival at the Charles Theatre and the New American Cinema which had been championed by Mekas. The column was subtitled "Hello and Goodbye to the New American Cinema."

Andrew Sarris ("Movie Journal," The Village Voice, 20 September 1962):

"Having recently served as a judge of the September Filmmakers' Festival at the Charles Theatre, I am reminded of the old story about Voltaire being conducted on a tour of all the vices invented for man, woman, and beast in the Paris brothels and behaving with such commendable aplomb that his hosts invite him for a return visit. 'No, thank you,' he replies. 'Once a philosopher, twice a pervert.' As for me at the Charles, it's once a critic, twice a masochist...

Since I have always been dubious about the inflated claims of the New American Cinema, I bent over backwards to be fair to new filmmakers even though I found more merit in one sequence of Minnelli's Two Weeks in Another Town than in the entire program at the Charles...

The New American Cinema is nothing but an idle pastime for intellectual ragpickers. Its art is so marginal that any critical evaluation degenerates into trivialities. My! That was a god shot! Look at the camera moving without wobbling! The montage is beginning to get to me! Unfortunately, most of the tentative efforts at the Charles are less the first step than the last stop, and this is particularly true of the polished relics of the avant-garde."

Sarris, who also wrote for Film Culture, had first substituted for Mekas in 1960 when Mekas took a break from the Voice. (DJ110) Eventually he was given his own column in the Voice so that in some issues there would be a film column by one or the other or both, with Sarris' column just called "Film." Sometimes they would be in conflict with each other. For instance, in the 18 March 1965 issue there was two columns - one by Mekas and one by Sarris - positioned next to each other on the same page. Mekas wrote, "I have to confess that very often I pity Andrew Sarris, my good friend - and I pity all other theorists of the auteur cinema who remain blind to some of the greatest film authors alive. Something must be and is completely wrong, totally wrong with our movie theatre system, with our distribution of works of art - that's where the trouble lies. The balance must be restored. There should be three or four theatre on Times Square playing Normal Love, Brakhage, Markopoulos, Harry Smith Ken Jacobs, Anger." (p. 23)

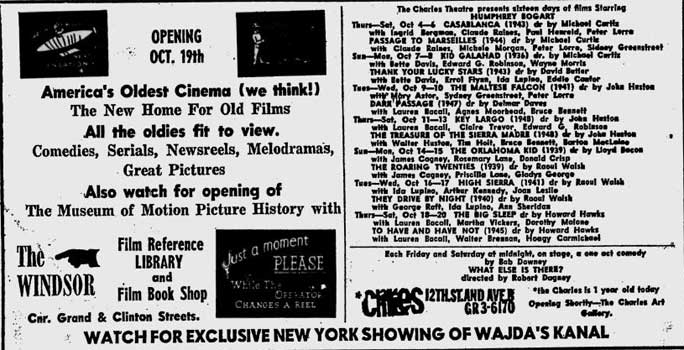

In the Charles ad for in the 4 October 1962 issue, the midnight film screenings were replaced by a live stage production. The ad also announced the opening of their sister cinema, The Windsor on 19 October. Yet by November the Charles Theatre was in serious trouble and on verge of closing - despite the previous claims of the popularity of their experimental film evenings or festivals.

Village Voice ad, 4 October 1962

During much of October, Mekas was with his brother filming Hallelujah Hills. His November 1, 1962 column for the Voice began "For the fourth week in Vermont, assisting on the filming of Hallelujah the Hills. It is cold here. We have our winter boots on. It was snowing for the last four days... What a difference from shooting a film in New York! During our five weeks of shooting we have seen only one cop. We were shooting in the the middle of the highway, blocking all traffic, when we saw the police car coming. We remembered all our troubles with the police during the shooting of Guns of the Trees. The cop, however, waved his hand, shouted a 'Good Day' to us, and away he went." (p. 17) In his November 15th column, he wrote, "Back in town. So many movies to see!" (p. 13)

In his November 22nd column of the Voice, Mekas warned, "The Charles Theatre is mobilizing its audiences for its own last stand. The door of the Charles Theatre might be closed forever soon. So everybody come and hold the door." (p. 13)

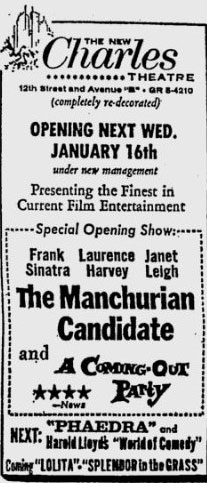

No ads for the Charles appeared in the November and December issues of the Village Voice although they were listed in the "At The Movies" section in November. In the November 15th issue they were listed as showing Frantic, Leda, House of Dracula and The Undead. In the November 22nd issue they were listed as showing Fear and Desire and The Killing. In the November 29th issue, however, there was simply a note: "Schedule unavailable at press time." (p. 13) There was no listings at all during December but in the January 10, 1963 issue, there was an ad for the Charles - now called The New Charles with the note that it was "under new management" and was "opening next wed. January 16th." Despite the claimed popularity of the experimental film screenings or filmmakers' festivals, the New Charles promised a more mainstream program: "the Finest in Current Film Entertainment."

Village Voice ad, 10 January 1963

Later in January, Mekas announced in his column that the magazine Film Culture would be presenting midnight screenings at the Bleecker Street Cinema, without mentioning that he was the editor and publisher of the magazine.