Trash cont.

page two

Trash in Germany

A year after it was released in the U.S., Trash was released in Germany and became the second highest grossing film in that country in 1971 - second only to Easy Rider. But when Warhol took a group of the actors to Germany to promote the film, he didn't include the most celebrated cast member - Holly Woodlawn. Woodlawn later recalled, "They didn't invite me because they were afraid of me. They were silly. It's okay. I don't mind. It's one of those things. I got over that. After Trash opened and I became a big star, I was invited here and I was invited there, but I was young and I couldn't deal with all that insanity and superstardom." (JOE102)

Warhol's Germany entourage consisted of Paul Morrissey, Joe Dallesandro, Jane Forth, Fred Hughes and Jed Johnson, with Bob Colacello joining them later. Colacello wrote about the tour in the Village Voice. According to his account, Warhol and his entourage, "began their German tour on February 17 in Cologne after a stop-over in London for the opening of the Warhol retrospective at the Tate Gallery. Detained in New York to put together the latest issue of inter/VIEW, Andy's film newspaper, I joined them two days later, just in time for the grand premiere of Trash in Munich. From there we travelled to Frankfurt, Berlin, back to Munich, back to London, back to New York - quite a trip!" (Robert Colaciello [sic], "King Andy's German Conquest," The Village Voice, March 11, 1971) The German trip also included Darmstadt, East Berlin, Cologne, and the Alps.

Colacello begins his daily account of the trip on the 18th:

Bob Colacello ("King Andy's German Conquest," The Village Voice, March 11, 1971):

Thursday, February 18, Munich: I arrived at the Arrabella, Munich's chic new hotel, just in time to be whisked off with Andy, Fred and Jed to a press conference and luncheon at the Hotel Conti, Munich's chic old hotel. Andy told me I had missed the Abendzeitung awards ceremony the night before which he described as "really up there." I had brought along the Life magazine "Nostalgia" issue which features Donna Jordan (who along with Jane Forth stars in L'Amour, Andy's made-in-Paris movie) and Fred in smart '40s outfits. "Ohhh, Donna's really up there now," Andy commented. "You too Fred."

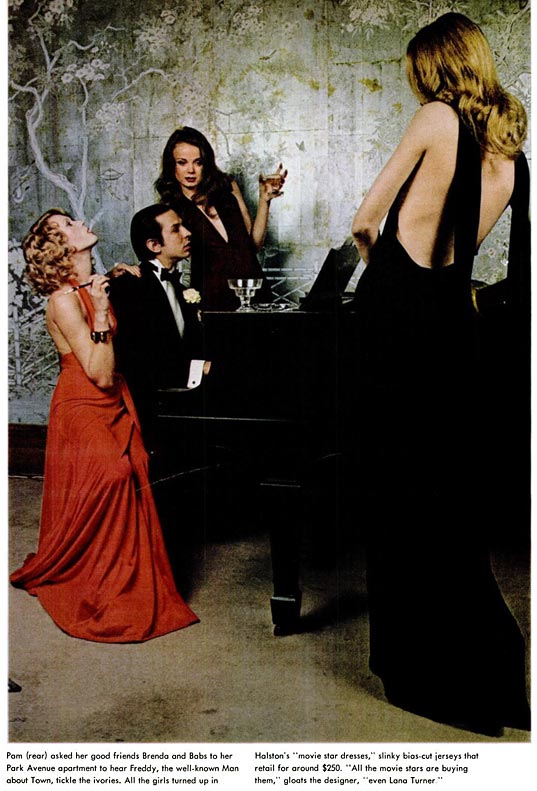

Fred Hughes posing for a fashion piece in the Nostalgia issue of Life magazine, photographed by Berry Berenson, February 19, 1971, p. 56

Still writing under the heading of "Thursday, February 18, Munich," Colacello describes the elaborate opening for the film put on by the German promoter, Constantin-Film:

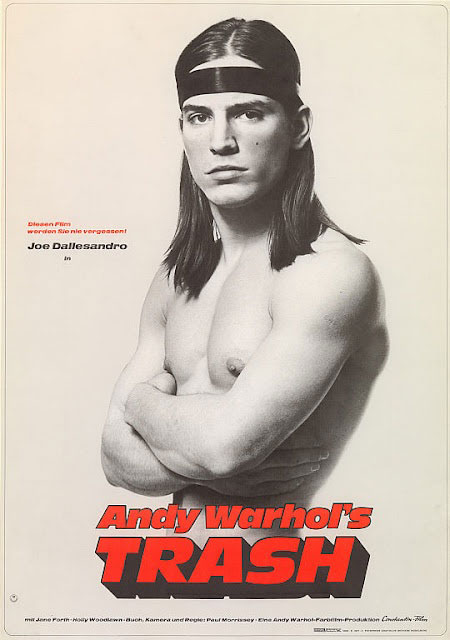

German poster for Trash

Bob Colacello ("King Andy's German Conquest," The Village Voice, March 11, 1971):

Three million Germans have paid to see Flesh [the previous year] so Constantin-Film, confident of commercial success, gave Trash the premiere to end premieres that night in Munich. The lobby of the Luitpold theatre, one of Munich's newest and largest (1100 seats), was jam-packed with photographer and fans upon our arrival, but more impressive than the crowd were the huge posters of Joe Dallesandro which covered the place like wallpaper. The people - mostly young and fashionable and affluent - seemed so small and insignificant against this naked, silent giant; the words "fan" and "star" assumed a sudden and intense reality.

It was equally strange and crazy and marvellous watching Trash dubbed in German. Both Paul and Andy could barely stop giggling as the lines were delivered. Jane and Joe were a bit more mystified by the foreign sounds emanating from their own images: Jane will probably go on saying "Oh mein god" for the rest of her life.

The party afterward - at the Arriflex studios - like all before it was dreamlike and spectacular. Images from Trash were projected onto the outside walls of the building; inside a large neon sign flashed "Welcome Andy Warhol's Trash." Everybody who is anybody in Munich was there, but I was on my 20th-or-so cocktail of the day so I did not catch their famous names.

After Munich, they went to Frankfurt on the 19th and gave a press conference. In the afternoon they were driven to Darmstadt where they were given a tour of the museum with "the largest collection of Pop art in the world." On Saturday, February 20th, they gave another press conference in Berlin and later that afternoon Paul, Joe, Jane Fred and Bob took a walking tour of East Berlin. According to Colacello, "Fred took Polaroids everywhere we went and sent them immediately to the Photographer's Gallery in London where they were sold for $12 apiece." (He doesn't indicate whether the photo credit was in Fred's name or Warhol's.)

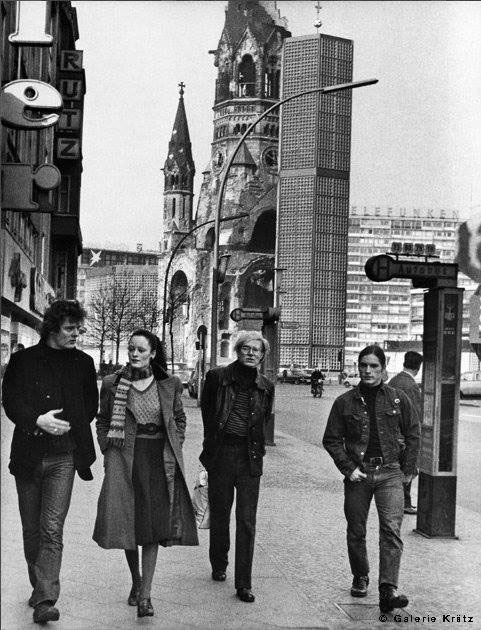

Paul Morrissey, Jane Forth, Andy Warhol and Joe Dallesandro walking up the Kurfurstendamm in West Berlin, 1971 (Photo: Leo Weisse at Gallery Kraetz)

On Sunday, February 21st they were back in Munich and on the 22nd they visited the offices of Constantin-Film where the president of the company presented them with books about Bavarian castles before they were taken to visit two of the castles in the Alps.

Bob Colacello:

We were not prepared for the snow which greeted us in the Alps - Jane was wearing open-toe shoes; Andy resorted to covering his head with a plastic shower-cap which for some strange reason he had taken with him from the hotel. Will McBride, an expatriate American photographer living in Munich, came along to make a movie about the day and was amazed at how fast we ran through the castles. It was not that we didn't find them interesting, but as Andy said: "I'd rather have heat than wealth."

The next day, Tuesday the 23rd, they were off to London.

Trash in England

On February 26th, three days after they arrived back in England, Jimmy Vaughan - the English distributor of Trash (which was yet to be released in England) - informally showed a copy of the film to the British censor (John Trevelyan) with Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol in attendance. According to the British Board of Film Classification case study of Trash, "Warhol and Morrissey were in London for the opening of Flesh and a Warhol retrospective at the Tate."

Although referred to as a "retrospective," the Tate Gallery exhibition catalogue notes, "At the request of the artist, the exhibition omits all work earlier than 1962 and several developments of the last eight years, and is restricted to the soup cans, disasters, portraits, flowers and Brillo boxes." The exhibition was originally organised by John Coplans for the Pasadena Art Museum (May 11 - June 21, 1970) and then travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (July - August), the Stedelijk van Abbemusuem, Eindhoven (October - November), the Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (December 1970- January 1971), the Tate Gallery in London (February 17 - March 28, 1971) and finally the Whitney in New York (May 1 - June 13, 1971.) (Richard Morphet, Warhol (exh. cat.), London: Tate Gallery, 1971)

Although the visit to London by Warhol and his entourage did coincide with the opening of the "Warhol" exhibition, it is unlikely that they were also in London for the opening of Flesh, as suggested by the BBFC. Flesh had originally opened at The Open Space on Tottenham Court Road (now the Odeon) on January 15, 1970 (JOE83), but had been seized by the police on February 3rd. After a battle with the censors, including arguments presented in the Houses of Parliament, it reopened in 1971 but probably not as early as February - although that may be the impression given in the official program of Trash which also refers to Flesh.

According to the official Trash program:

In February 1971, the story began. The Andy Warhol exhibition opened at the Tate. That week, John Trevelyan, the censor, saw Trash. At last, said the censor, Morrissey and Warhol had come to terms with "professional commercial film-making." The matter of a certificate was raised and left in the air.

Flesh was due to open in Chelsea. In spite of giving Flesh a certificate, the censor's office was apprehensive. Was the censor going to be inundated by letters from moral vigilantes? Flesh opened and ran week after week.

An article in The Times, however, gives the impression that Flesh opened in about April 1971. The author of the article, which is dated as April 16, 1971 in the UK Trash program, remarks that "It is pleasing to note that Flesh, the very remarkable Andy Warhol/Paul Morrissey film about a male hustler in New York, has finally been given an X certificate uncut and is now on public exhibition at the Chelsea Essoldo."

The Times, April 16, 1971

Bob Colacello wrote about the London trip, both in his Village Voice article about the Germany tour and in his published account of his Warhol years - Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (NY: Harper Collins, 1990).

Bob Colacello ("King Andy's German Conquest," The Village Voice, March 11, 1971):

Sir Norman St. John Steves, Conservative Member of Her Majesty's Parliament, is not the sort of gentleman one would expect to be a great fan of Andy Warhol films. He is...

Sir Norman, one of the staunchest Parliamentary defenders of Flesh after it was seized by London police last February, and host of this totally refined reception, seemed as please with Joe Dallesandro as his aunt was with Jane Forth.

Although Colacello put his account of London at the beginning (pre-Germany) section of his article, it appears to actually be a description of the stop-over on the way back from London - similar to the account he gives in his book Holy Terror.

During the battle with the censor over Trash, the MP that Colacello mentions in his article, Sir Norman St. John Steves, wrote a letter supporting the film which was later reproduced in the UK program for the film.

The impression given by Bob Colacello is that the shared Catholicism of Warhol and his entourage might have helped their cause. He put a particular emphasis on this in his account in Holy Terror. (Note that in his account in Holy Terror below, he writes that Flesh had been seized, just as he had mentioned in his Voice article, but does not say in either source that they were there for the opening of Flesh as claimed by the BBFC account above.)

Bob Colacello (Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (NY: Harper Collins, 1990), p. 52):

On our way back to New York, we stopped in London, where the Tate Gallery was giving a major Andy Warhol exhibit, and a major Andy Warhol scandal was brewing. The English film censor had seized a print of Flesh when it was shown in a London art theater the previous year, and had now forbidden the distribution of Trash...

The highlight of our London visit was a reception in Andy's honor at the House of Commons... Our host was Sir Norman St. John-Stevas, a Conservative Member of Parliament (and later Minister of the Arts under Mrs. Thatcher)... There were only two other guests, besides the eight of us: Edna O'Brien, the lusty and literary Irish Catholic novelist, and a Roman Catholic priest named Father Ryan, who both immediately hit it off with Joe Dallesandro. What did we talk about? Catholicism. I'm not being facetious. Sir Norman, like most English Catholics, was rather energetic and proud in his devotion to the Roman Church, and saw the censorship of Trash as typical puritanical Protestant behavior." (BC52)

When Vaughan, Warhol and Morrissey showed Trash to the British censor on the 26th, they were told that there might be problems because of the portrayal of drugs in the film. Trevelyan thought it best to leave the decision to his successor, Stephen Murphy. Murphy viewed the film on June 14, 1971 and advised that "the film would require cuts at best, and at worst may be denied a certificate altogether." He suggested that they first try to get a local certificate from the GLC - The Greater London Council. (BBFC1)

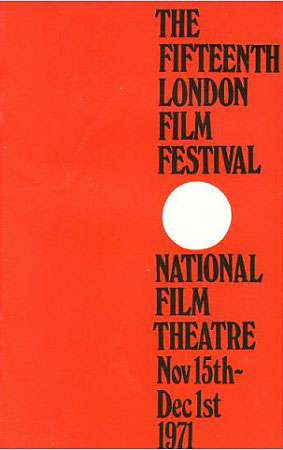

On November 19, 1971, Trash, still without a certificate, was shown at the Fifteenth London Film Festival at the National Film Theatre (often abbreviated as the NFT).

Fifteenth London Film Festival poster, 1971

The Festival films were reviewed in the Winter 1971/72 issue of Sight and Sound magazine and the review of Trash made reference to the censorship battle over the film.

John Russell Taylor ("Paul Morrissey/Trash" in "London Festival," Sight and Sound, 41:1 (1971/1972:Winter) p.31):

... the film should be, from the censors' point of view, one of the most evidently moral and improving on the subject of drugs; and their arguments for refusing it a certificate, based almost entirely on its drug aspects, seem more than usually ludicrous, indeed totally incomprehensible.

As in the U.S., Holly Woodlawn's performance in the film was singled out for praise in the UK review:

John Russell Taylor ("Paul Morrissey/Trash" in "London Festival," Sight and Sound, 41:1 (1971/1972:Winter) p.31):

But above all there is Holly Woodlawn. Holly, needless to say is one of the Warhol drag queens. And it really is needless to explain: first time round one may be intrigued at the outset by the problem of what exactly she is, but before long one accepts completely that she is what she says she is, a woman. It does not matter what she was born as and may still, for all we know, anatomically be. She is a woman giving a performance, and a performance which is by any standards mesmeric. Apart from Joe, she is the only recurrent character in the film... Joe is, as he has been established, the still, dead centre round which other people's passions revolve, while Holly is the dynamic element. And while what she says and does is often fiercely funny, she does bit by bit acquire her own dignity. Morrissey's treatment of her is masterly.

At the film festival screening, questionnaires were distributed to the audience who were asked to vote on whether or not the film should be granted a certificate. Only seven audience members indicated that it should not be granted a certificate. But the British Board of Film Classification thought the results might have been skewed in favour of the film given the liberal nature of a film festival audience. They re-did the poll by including a greater assortment of people, including a group of "middle aged housewives" bussed in for the screening.

BBFC:

Murphy [Secretary of the BBFC] felt that the self selecting nature of the NFT Festival audience ruled it out as an indicator of general public opinion and therefore decided to commission some research of his own from the University of Leicester's Centre for Mass Communication. This research, undertaken at the end of 1971, involved showing the film to a group of 86 individuals and asking for their reactions. In addition to a number of university students, the researchers also bussed in a group of ‘middle aged housewives’ to seek their views. The results, which were not presented to the BBFC until February 1972, showed that the majority (58 per cent) were in favour of passing the film as it was and did not think that it promoted drugs (only six people expressed concerns in this regard). (BBFC1)

Despite the majority being in favour of passing the film, sixty-two percent of the audience were offended by the mainlining scenes and 19 percent by the scene where Holly masturbates with a beer bottle. The BBFC then showed the film to a Manchester audience and although most of the Manchester audience agreed that Trash should get a certificate, the amount of audience members who disagreed was higher than in London - 214 to 48. As far as Murphy was concerned the higher number of disapprovals confirmed his suspicions that people outside the capital would be particularly offended by the film.

On December 13, 1971 a letter was published in The Times, signed by 13 film critics, objecting to the refusal to classify Trash, especially since films like Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs were allowed to be screened. (Straw Dogs had opened in London on November 25, 1971) Two days after the letter appeared the BBFC also passed A Clockwork Orange without requiring any cuts.

In June 1972 the Jimmy Vaughan again asked the BBFC to reconsider the ban on Trash. Although the BBFC restated their view that the full, uncut, version of the film was not acceptable, they suggested that it might be possible to classify the film if cuts were made. Paul Morrissey flew to London on July 15, 1972 to discuss possible cuts to the film. In consultation with the distributor, one minute and eight seconds were cut from the film. The edited version was presented to the BBFC on July 24, 1972. More cuts were requested and made - now a total of two minutes 48 seconds worth of cuts. According to the BBFC "The material that was reduced in the X version was as follows:- (i) the opening fellatio scene [in fact masked fellatio], (ii) the first heroin injection scene, (iii) Holly’s masturbation with a beer bottle. Other cuts that were initially suggested were waived."

However, in addition to the cuts required by the BBFC, Jimmy Vaughan decided to make his own cuts. Vaughn explained to the Board, that “During the re-editing of Trash to meet the requirements of your Board, I felt I might as well make certain cuts of my own [...] I would also like to mention that I myself removed two scenes of blood going into the syringe and several other cuts which I felt myself were either boring or possibly distasteful”.

According to the BBFC, "...Vaughan’s own cuts were considerably more severe than those requested by the BBFC and amounted to the deletion of a further eight minutes of material. By the time Trash hit UK cinemas, nearly 11 minutes were missing, mostly because of the actions of its distributor rather than the BBFC." (BBFC1)

The edited version of the film was given an "x" rating on November 9, 1972. It was finally screened on February 8, 1973 - delayed because Vaughan reportedly wanted the opening to coincide with the publicity that was bound to be generated by the planned broadcast of a TV documentary on Warhol, directed by David Bailey. The broadcast of Bailey's documentary was delayed, however, due to the it's own censorship problems. After a press screening of the documentary in January 1973, the press had a field day - referring to it "shocking, revolting and offensive" (among other things). The Daily Mail seemed particularly outraged by a scene where "a fat female artist... dyes her breasts and then rolls about on canvas 'painting'." (SR) (They were, of course, referring to Brigid Berlin and her tit paintings.)

On Tuesday, January 16th, Ross McWhirter, a sports journalist and co-editor of The Guinness Book of Records, filed a writ to stop the broadcast of the documentary and a court decided that the film should not be broadcast. McWhirter hadn't actually seen the film but had read the press reports. After a number of court battles, the documentary was finally broadcast on March 27, 1973. (SR)

By that time, Trash had already been shown in cinemas. It was reviewed in the February 11, 1973 issue of The Observer by jazz performer and writer, George Melly. The review was headed "Behind the six and drugs is a film of true insight."

George Melly (The Observer (London), February 11, 1973):

At long last, Trash has opened at the London Pavilion and, thanks largely to the efforts of Mr McWhirter and his associates, there are queues in the rain and the film's distributor, the indefatigable Jimmy Vaughan, will reap a rich reward for his persistence.

There are three cuts and, although I'm loth to have to admit it, two of them marginally improve the film [produced by Andy Warhol]. The fellatio scene at the beginning has been trimmed, and while the logic escapes me, it lasts quite long enough to establish the hero's heroin-induced impotence. The blood pulled into the syringe and then repumped back into the vein is, for those of us who tend to be queasy about needles anyway, something of a relief.

Only the beer bottle sequence, now cut to a point where the more obtuse may wonder what Miss Woodlawn's doing with it, damages the film's impact, and while I'm appalled at the right of the censor to come between artist and public, it's only fair to say that Mr Murphy has wielded his scissors with maximum discretion.

Now the fuss is over, it's possible to view the film dispassionately and it is remarkably good in every sense of the word. The director, Paul Morrissey, is cool, but that doesn't mean he isn't compassionate. He is non-censorious, but this isn't the same as not caring. Joe, the handsome passive junkie whom everybody wants to turn on, is a figure of true pathos, and while those who crawl and writhe over him may seem lacking in restraint by conventional standards, they are never less than human.

What emerged was the way Warhol's world presents a wicked caricature of the straight world. Miss Woodlawn's junk-filled flat is for her a true love nest. She works like a Trojan to make it a home and while her nagging may verge on the over-emphatic she really has got rather a lot to put up with, and is suitably touched when Joe tries, in a rare escape from apathy, to sweep the floor.

The film is a comedy, however black. The girl with the big boobs dancing and singing on her very own home vaudeville stage, the pimply Fritz the Cat-like schoolboy slumming for kicks, the mindless rich bitch and her despicable husband, Miss Woodlawn herself with her extraordinary tongue, an organ with an apparent life of its own, are really very funny.

It may be possible to find Trash heartless, but to do so, I think, shows inattention. Every now and then, the camera settles on Joe's beautiful dead face and for a moment there flickers behind the eye a sense of pained, numbed outrage at what is happening to him. Once, a small tear runs down his cheek. These transvestites, nymphos, junkies are in hell. They frot and turn on to give them the illusion of living, the shadow of happiness. For all its superficial air of improvisation, this is a carefully considered, totally responsible film.

As noted in the review, the version of Trash that Melly saw was the edited version. It was not until 2005 that the original, uncensored version of Trash would be released in the U.K. - 35 years after the U.S. release of the film.