Andy Warhol's L' Amour

by Gary Comenas (2015)

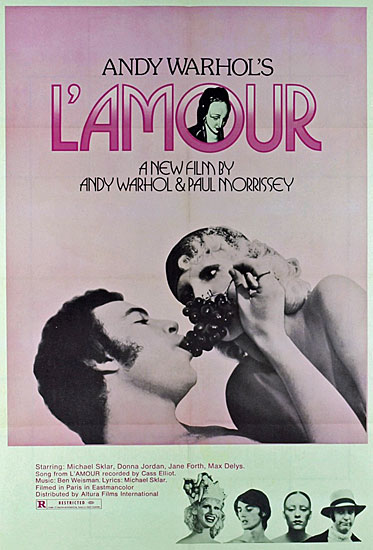

Poster for Andy Warhol's L'Amour

Cast: Michael Sklar, Donna Jordan, Max Delys, Patti D'Arbanville, Karl Lagerfeld, Coral Labrie, Peter Greenlaw, Corey Tippin, Jane Forth

Directors: Paul Morrissey, Andy Warhol/Writers: Paul Morrissey, Andy Warhol/Producer: Paul Morrissey/Cinematography: Jed Johnson - Eastmancolor/Editing: Jed Johnson, Lana Jokel/Music Composer: Ben Weisman/Theme from L'Amour recorded by Cass Elliot/Distributor: Altura Films International/Running Time: 90 minutes/Rated: R (VC/MF)

Directed by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey/Editors: Lana Jokel and Jed Johnson/ Director of photography: Jed Johnson/Music: Ben Weisman/Distributed by Altura Films International/ Running time: 90 minutes/ Rating: R.

-----

Andy Warhol's L'Amour came and went so quickly that few people actually saw it. From reviews it came across as somewhat purposeless - not art, not cult and not entertainment. "Wane" was how one reviewer characterized it.

It also didn't have any of the Warhol/Morrisey superstar transvestites in it - no Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis or Holly Woodlawn. Karl Lagerfeld's presence should have made the movie more interesting but fashion designers don't necessarily make the best improvisational actors. Michael Sklar, who played the welfare officer in Trash and a rich American in L'Amour, made an attempt at superstardom during his Warhol career but ultimately only managed semi-superstardom at best.

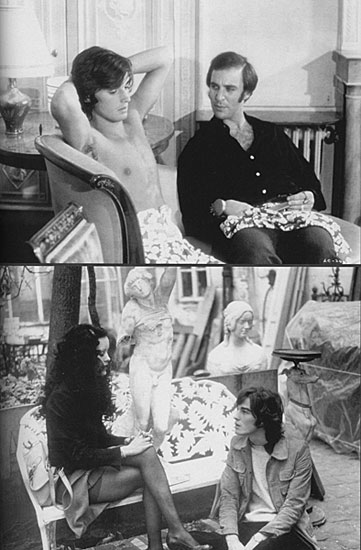

Still, despite the short run, there remains an interest in the film and it's curious that there are no plans to screen it, if only for historical reasons. It was (allegedly) shown in conjunction with the exhibition "Andy Warhol: The Late Work" that ran at the Museum Kunst Palast in Düsseldorf from 14 February - 31 March 2004 before travelling to the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz (13 June-12 September 2004), the Liljevalchs Konsthall Stockholm (22 October - 9 January 2005) and finally the Musée D'Art Contemporain de Lyon (27 Janury - 8 May 2005). The catalogue for the exhibition included two promotional photographs from the film:

Two promo stills from L'Amour reproduced in the Andy Warhol. The Late Work exh. cat.

The lack of any other screenings might be due to the co-direction credit, shared between Morrissey and Warhol, which possibly complicated the ownership of the film - or it simply might be that the film was so bad that it wasn't even bad enough to be good.

Fortunately we have an eye-witness account of the filming of at least some of the scenes because a journalist, Sally Beauman, travelled to Paris to watch Warhol and his crew shoot L'Amour (which was known at the time as Les Beautés or The Pissoirs of Paris) and wrote about it in the 5 February 1971 issue of The Telegraph magazine under the title of "But the People are Beautiful."

Sally Beauman ("But the People are Beautiful," The Telegraph, 5 February 1971):

Andy Warhol sits in the corner of this Paris apartment like a small silver seraph... Around him is a mild form of chaos, which he studiously ignores. He, or rather Andy Warhol Productions, which is a group name for Paul Morrissey, Fred Hughes and Jed Johnson the sound man, all of whom filmed Flesh, and more recently Trash, are in Paris to make their first European movie to be entitled Les Beautés - a French Farce. Alternative title: The Pissoirs of Paris. (SBE422)

Beauman's claim that Fred Hughes and Jed Johnson "filmed" Flesh and Trash isn't quite true. Johnson is credited with the sound and editing of Trash but Fred Hughes isn't normally credited with playing a part in the actual making of either film. (FPM/VTR)

Although Beauman doesn't identify the Paris apartment as belonging to Karl Lagerfeld, she does say that the room they were filming in "could only have been created by an interior decorator, and the interior decorator/designer - Karl Lagerfeld - is, in this case, also acting in the movie." The apartment was on the Rue Bonaparte in St. Germain - "a few yards from the Seine." (SBE422-23)

According to Beauman, the filming wasn't going well - at least not initially.

Sally Beauman:

It is certainly fairly peaceful in the apartment now: Fred Hughes is on the phone, Karl Lagerfeld is looking in the mirror, the lights are smoking, Paul Morrissey lounges on the Thirties lamé. The only trouble is that - apart from Karl - there is no sign of the other actors. On the phone Fred Hughes voice takes on a plaintive note:

'What d'you mean you can't come over, Patti, we're supposed to be shooting. Well, there's a bathroom here if that worries you. What, you won't? Patti, what were you doing last night?' He pauses to give the room a thumbs down signal. 'Well, how about tomorrow? You're going to Venice tomorrow? But Patti, we're shooting a picture.' He hangs up. There is a silence. 'Why not get Max,' squeaks Paul Morrissey. 'We could shoot a scene between Karl and Max. Max could tell Karl he's been having an affair with Patti.'

'Has he been having an affair with Patti?'

'No, but he could do.'

Andy Warhol makes his first suggestion.

'We could get Jane and Donna over, ' he says mildly.

'Jane and Donna are at the hairdressers having their hair dyed again.'

Fred Hughes gets on the phone once more. It is now 3.30.

'Hello, Max, can you come over now? What, you just work up? Well, that doesn't matter,come anyway.' (SBE426-7)

Beauman stays until Max arrives and witnesses a small scene between Max and Lagerfeld where Max tells Lagerfeld that "Er, Karl... I zink maybe you should know, I make a leetle zing with Patti," and Karl responds "what is a little thing?"

On another day some of the cast assembled at a pissoir to film another scene:

Sally Beauman:

We have arrived at the pissoir and are waiting for the van to materialize bringing the equipment. Andy and the girls. Fred Hughes tells Michael Sklar how they will be filming. It appears this does not correspond with how Paul Morrissey had said they would be filming. Michael puts up a fight: 'But I've prepared this whole scene in my head and now you're telling me it's all different. I mean that throws out all my motivation...

We all stare at the pissoir for want of anything else...as the cameras arrive. The camera, with Warhol operating it, is well hidden inside the van, which backs up on the pavement so it can focus most effectively on the starring pissoir... Donna and Jane and Michael line up further down the street. Paul Morrissey tells them to do one thing: Fred Hughes tells them to do another...

It's all getting a little temperamental; the leading actresses are glowering; clearly there are some considerable ego trips involved in this picture... in the midst of all the fracas, Andy Warhol, hand on the camera button, gives a gentle sigh. 'Oh, come on,' he says in his sweet way, 'do anything. It doesn't matter what they do...' And it works like magic.

The three stars converge on the pissoir... Donna cosies up to the pissoir, and, deodorant cake in hand, goes into a series of gummy pin-up smiles, of lightning cheesecake postures...

It is the first pissoir of many. There is then the St. Germain pissoir. The Arc de Triomphe pissoir. The Pigalle pissoir. In each they do several takes until they have one that is good, or the police arrive - whichever happens first. On one particularly good take Andy forgets to press the button, and only when they are finished realises the camera did not roll...

Later the same day we watch some rushes. The movie screen is set up in Andy's apartment, and everyone sits on the floor squinting at the flickering images. All the outdoor shots are over-exposed, so the actors and actresses appear to float around Paris in a ghostly white mist...

There are several takes of Donna on the telephone; some takes of Donna and Jane walking around Paris with their friends Jay and Corey; there is a jealous scene between Max and Michael in bed, during which Max - who is naked - firmly keeps a pillow between his legs: clearly this is not going to be as explicit as Flesh or Trash - but maybe that is all part of being a Hollywood-style commercial entertainment. Except, of course, that it obviously is not going to be that either: a cast of mostly amateurs improvising lines to one 16mm camera is not Hollywood; it is alas, as becomes increasingly clear, not Warhol either. The freshness and exciting haphazardness of his early films has gone. (SBE430-31)

Beauman's description is interesting for serveral reasons. Although Warhol gives the impression of being 'seraph-like,' it's his instruction to "do anything" that gets the ball rolling as far as the filming is concerned. Beauman's description also notes that Warhol was doing the actual filming. It was Warhol who was behind in the camera in the scenes that she was writing about. Warhol was directing the action by effectively telling the actors to improvise while the others shouted conflicting directions at them in a chaotic and ineffective manner.

This conflicts with the impression given by some writers that it was Morrissey, alone, who directed L'Amour. According to Maurice Yacowar in The Films of Paul Morrissey (Cambridge University Press, 1993), "It is probably inaccurate to speak even of 'collaboration' in the Warhol-Morrissey films... Paul Morrissey was the presiding force of creative control in the 'Warhol films' from My Hustler to Lonesome Cowboys (1967). The casting, cuing of actors, prompting of plot, arrangement of location, editing, and 'whatever directing these films had, came from me,' Morrissey avows. Morrissey even set the lights and prepared the camera; all Warhol had to do was operate it. With the advent of outside financing on L'Amour (1972), Warhol gave up even his minimal activity running the camera, turning it over to Jed Johnson, and withdrew from the set. " (FPM3)

Ms. Beauman's account indicates otherwise. Morrissey may have wanted to add "plot" but what if Warhol didn't want more "plot?" The lack of a plot is one of the defining aspects of a Warhol film. Warhol was "anti-plot." When there was a "plot" in one of Warhol's films it was usually minimal and often nonsensical.

According to Warhol's friend and biographer, David Bourdon, and Bob Colacello (the on-again off-again editor of Interview magazine), Warhol killed two birds with one stone with L'Amour. Not only did he make a movie, he also added to his burgeoning collection of art deco pieces. According to Colacello, while Warhol was on a press trip to Germany in February 1971 he would "check out the antique shops for Art Deco pieces" and later claim that they were "props" for L'Amour. (BC51) Colacello recalled Warhol would "every so often give Jude [O'Brien] some Bakelite bracelets or pins - not as many as he gave Jane [Forth] and Donna [Jordan], but enough to make her feel wanted. These plastic Art Deco trinkets cost next to nothing back then, but they were just coming into fashion and Jude loved showing them off to our Columbia friends. Andy, of course, was tax deducting them as 'costumes' for L'Amour." (BC57) When Warhol moved his operations to 860 Broadway in 1973, many of the furnishings in the executive office were art deco. David Bourdon recalls, "Andy played down the importance of his [art deco] collection, denying that he had ever made a shopping trip to Paris and claiming that the table and chairs were just 'used furniture - stuff we used for a movie [L'Amour] we were making in Paris.'" (DB326)

Although L'Amour would not be released until 1973, it was filmed in September 1970 according to Victor Bockris in his biography of Warhol, and edited in the spring of 1971 according to Bob Colacello. Colacello recalls, "The spring of 1971 was a great time to be working at the Factory. Andy Warhol's Trash was still filling theaters in New York, California, and Germany; Andy Warhol's L'Amour was being edited; Andy Warhol's Women in Revolt was being shot." (BC54)

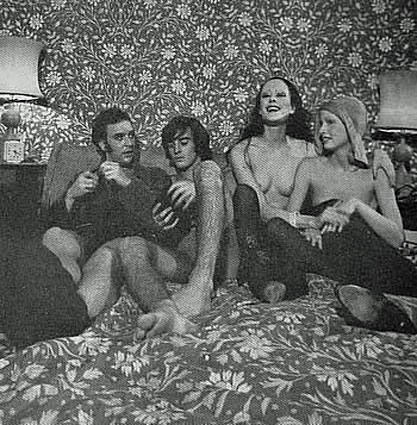

Michael Sklar, Max de Lys, Jane Forth and Donna Jordan in L'Amour

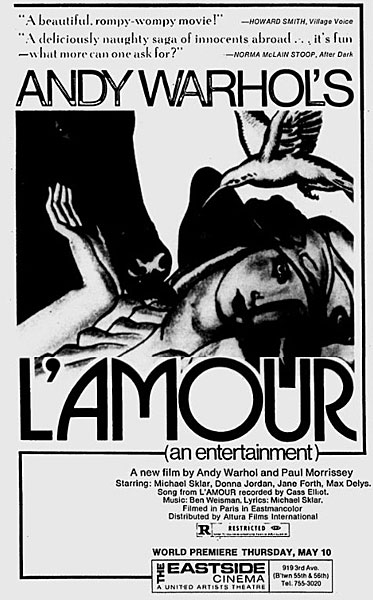

The first ad for L'Amour in the Village Voice was a large ad announcing the "world premiere" of the film on 10 May 1973 - in the 10 May 1973 issue of the Voice:

Village Voice ad, 10 May 1973

Despite the claim of it being the "world premiere" on the 10th, the film must have been shown previously as it features quotes from previous screenings. Howard Smith of the Village Voice and the journalist quoted from the gay monthly After Dark must have either already seen the film or pretended to have already seen it. Smith wrote the "Scenes" column for the Voice but L'Amour was not mentioned in it in the month leading up to the film. In any case, the comments on the ad aren't exactly overwhelming. What is a "rompy-wompy movie?" Is it good or bad? The After Dark reviewer called it "fun." But was it any good?

The ad also credits ex-Mama and the Papas' lead singer, Cass Elliot, as the singer of the film's song, Song from L'Amour. Another ex-member of the Mamas and the Papas, John Phillips, had meanwhile been working on the music for what would become an even greater flop for Warhol than L'Amour - a Broadway musical directed by Paul Morrissey called Man on the Moon.

The day after L'Amour opened at the UA Eastside Cinema, Vincent Canby's review of the film appeared in The New York Times. He wrote that L'Amour was "so wane it makes one remember Trash and Women in Revolt as robust classics of their kind:"

Vincent Canby (The New York Times, 11 May 1973):

L'Amour, the newest chapter in the continuing series of Andy Warhol-Paul Morrissey soap-opera put-ons, takes the Factory gang to Paris where Michael (Michael Sklar), a rich American, represents his father's firm, the Watkins Bathroom Deodorant Company. Michael is head over heels in love with Max (Max Delys), a street hustler who looks like a French version of Joe Dallesandro. Michael, however, is fond of Jane (Jane Forth), a self-described American high-school dropout who has come to Paris to model with her best friend Donna (Donna Jordan), who would sort of like to marry Michael so they could legally adopt Max.

This is a film unafraid to ask questions. Will Michael find happiness with Max? (No.) Will Max find satisfaction with Jane? (Not really, since Jane says she gets more excited buying make-up.) Is this sort of thing funny? (Only intermittently.)

Were there fewer demands for one's attention, L'Amour might be worth sitting through for the occasional comic moments, such as Michael's big renunciation scene with Max ('I'm growing older, Max...'), which leaves Michael so shaken that all he can do is crochet. Michael, however, is but a poor, hairy substitute for Sylvia Miles, who handles this sort of comedy better. There is also a nice title song, sweetly sung from time to time by Cass Elliot, and a rather pretty scene where everyone roller skates around the Palais de Chaillot. It looks like a high-fashion layout gone a bit looney.

These things simply are not funny or important enough to compete with late-night talk shows, a new album by the Carpenters, the Watergate scandal, kung-fu movies, dining at Blimpie's, and a number-one best seller by Jacqueline Susann. We live in a in a time and place in which first things must come first.

L'Amour which opened yesterday at the UA Eastside Cinema, is so wane it makes one remember Trash and Women in Revolt as robust classics of their kind. (VC)

A few days later, a scathing review by Judith Christ appeared in the May 14th issue of New York Magazine:

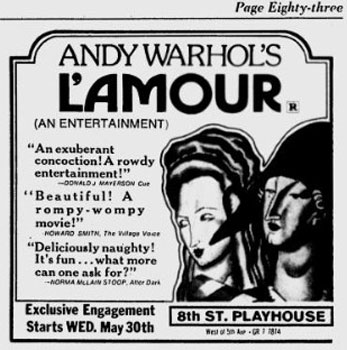

The run at the UA Eastside didn't run long. Andy Warhol's L'Amour was still advertised as playing there in the following week's Village Voice - "World Premiere Now" at the Eastside Cinema - but by the next week there was no ad for the Eastside and a new ad for the 8th Street Playhouse saying that L'Amour would be playing there exclusively beginning May 30th:

Village Voice ad, 24 May 1973

Andrew Sarris's review of the film was published in the Voice the day after it opened at the 8th Street Playhouse:

Andrew Sarris, Village Voice, 31 May 1973:

L'Amour is not quite as startling as Trash or as striking as Women in Revolt, but that is largely because it doesn't rely on the relatively facile dialectics of drag. Since Morrissey became the more active partner of the Warhol-Morrissey team, the technical quality of the movies has been steadily improving. This raises an interesting problem for formal criticism in that Warhol's earliest 'technique' was so minimal that it almost qualified as something else whereas Morrissey's relative professionalism takes him out of the minimal category without any appreciable advance toward the still distant domains of the most masterful mise-en-scene.

In this instance L'Amour comes so close to being a well-modulated movie that one wonders why the director doesn't turn off the faucet of falsetto histrionics more often than he does, particularly in the monotonously coy confrontations between Michael Sklar's prissy pederast and Max Delys's soulful stud...

By making its freaks only a tiny portion of the Parisian scene, L'Amour confirms for me at least all the magic and mystery of Paris. And this time around, I become fondly attached to the Warhol-Morrissey menage for, of all things, being so intransigently American! What has never been acceptable as social allegory is now finally validated as a personal myth. Goodbye Jean-Paul Startre [sic], and hello, Jean Cocteau. (ASA)

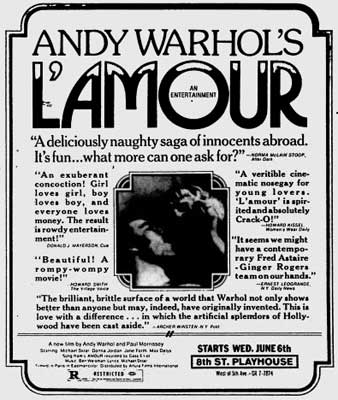

In the same issue of the review, the ad for the film in the Village Voice now said the film "starts Wednesday, June 6th, at the 8th Street Playhouse even though, as the above ad shows, it had previously begun its "exclusive engagement" at the 8th Street Playhouse on 30 May.

Village Voice ad, 31 May 1973, p. 80

The following week's issue of the Village Voice - the June 7th issue - had an ad for L'Amour but by the issue after that - June 14th, there was already a different film playing at the 8th Street Playhouse. The film appears to have had a total run of about three weeks before it was taken out of circulation completely.

Around the same time that Warhol's film was failing, John Waters' film, Pink Flamingos, was playing an extended run in New York after a successful tour of colleges the previous year. People who were previously shocked by Warhol's depictions of people shooting up in films like The Chelsea Girls, were even more shocked by the image of an overweight transvestite eating dog faeces in Pink Flamingos. L'Amour was tame by comparison. It was neither so trashy that it was good nor so good that it didn't have to rely on trashiness to sell it. Even worse for Warhol was that Waters was eventually able to do what Warhol was trying to do unsuccessfully with L'Amour - to evolve from making trashy films to entertaining films that appealed to the general movie-going public and would, therefore, be able to get financing from the major studios.