Andy Warhol: From Nowhere to Up There

an oral history of Andy Warhol's early years

by Gary Comenas

page twenty-four

David Bourdon: Gold, real or ersatz, fascinated Warhol for the wealth that it represented as well as for its glitz. During 1957, he self-published still another promotional item, this one with the alluring title A Gold Book. It was a forty-page bound volume, published in an edition of one hundred, and dedicated to 'Boys/Filles/fruits/and flowers/Shoes/and tc [Ted Carey] and e.W [Edward Wallowitch].' (DB51)

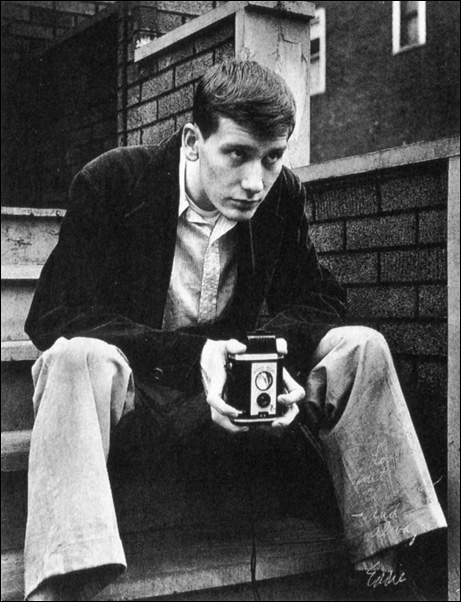

Andy Warhol's boyfriend, Edward Wallowitch ("Eddie") (Photographer unknown) (AWMU173)

Ted Carey: Edward Wallowitch... was a photographer... who was a very close friend of Andy during the early '50s.... (PS258)

Georg Frei/Neil Printz: (authors of The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné): Edward Wallowitch was a professional photographer who met Warhol through Nathan Gluck, probably in the late 1950s. (GF470)

Patrick S. Smith: ... [Nathan] Gluck introduced Warhol to the photographer Edward Wallowitch and his brother John Wallowitch. Edward Wallowitch had just graduated from high school and had some photographs chosen and bought by Edward Steichen to be in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Wallowitch often photographed children in his neighbourhood in Philadelphia. Such a photograph was traced by Warhol and used as a promotional flyer...

According to Gluck, the photographer and Warhol became very close friends, and Warhol often used Wallowitch's photographs as the basis of drawings, such as some in Warhol's so-called Boy Book, as well as Campbell's soup cans for Warhol's Campbell's Soup Can pop art paintings. The photographer lived incognito in Florida and sold photographs to religious organizations: photos of underprivileged children for promotional material. (PSC62)

[Although the Boy Book was never published, it's possible some of the images were included in A Gold Book.]

Patrick S. Smith: In 1957, Warhol printed the promotional suite of elegantly bound drawings of children and other 'Boy Portraits.' Entitled A Gold Book, the 19 blotted drawings are printed on gold paper. Coloured tissue papers are between the pages, and some of the drawings included hand painted overlays of Dr. Martin's dyes. The drawings are either traced from photographs by Edward Wallowitch or from Warhol's own sketches. (PS67)

Rainer Crone: In this drawing of the James Dean type [on the front cover of A Gold Book (1957)], clothing assumes the function of a social gesture. The iconological significance of the drawing is not solely due to the type of person portrayed, but owes much to his pose... This accurately characterizes the attitude of a social group for a whole generation; the rebellious beatnik stance, later to be adopted, in the 1960s, by the so-called hippies and their counter-culture. (RCA69)

Billy Name (Warhol superstar): During the Beat era, the Bohemian Greenwich Village was 'The Village.' It was Cafe Figaro, which was the coffee shop to hang out in. Washington Square Park was filled with bongo drum players. All of the clubs had jazz musicians who did heroin and smoked marijuana, and you could hang out with these people and just groove. So, Ginsberg and Corso and Burroughs and the whole clique were the equivalent to the art culture what Marlon Brando and James Dean, the rebels, were to the film culture. And in the authentic cultural world, the kings were the poets. (CO32)

James Campbell: [In 1959] Life [magazine] printed a picture of 'a happy home in Kansas' - a living room where the four-square family congregated for a 'TV session,' or gathered around the photograph album ('unfailing fun'). This was contrasted with a 'hip family's cool pad' in Venice, California, where the 'emphasis is all on "creativity" with no interest in physical surroundings.' The occupants were shown sprawled on mattresses on the floor, with empty beer cans lying around.

Soon there was Rent-a-Beatnik, The Beat Generation Cookbook, and a MAD magazine special... Rent-a-Beatnik was the brainchild of Fred McDarragh's [sic], a photographer who was making a speciality of beat (and beatnik) scenes. McDarragh [sic] placed an ad in the Village Voice: RENT genuine BEATNIKS/Badly groomed but brilliant (male and female). The rental price was $40 nightly. (MAD countered with 'Rent a SQUARE for your next Beatnik Party.) Props such as bongo drums and guitars were extra. (JCA249)

[Note: Similarly, about ten years later, Warhol reportedly offered his superstars for rent. According to Michael Ferguson, biographer of Warhol star Joe Dallesandro, Joe could be rented out for $4,500 a week - more than $28,000 in 2013 terms. (MF6) g.c.]

Fred McDarrah: In the late 1950s, there weren't the divisions between writers, dancers, poets, and musicians that there are today. Those in the 'avant garde' - or anyway those who thought of themselves as being in the avant garde - grouped together, living in the same neighbourhoods, supporting each other's work by attending concerts, openings, readings, and hanging out together. Once I became friendly with the artists, meeting musicians and poets was easy, and soon I was documenting the entire scene...

What really set me apart from the others was that I had a daytime job on the Village Voice, a recently started alternative weekly newspaper that thumbed its nose at the establishment and told its small world all about the radical, crazy Beat Generation. In the paper's early days of the 1950s, each issue ran about twelve pages, with articles discussing art, poetry, music, film, dance and the avant garde. Since I had worked on Madison Avenue in advertising, I became the Voice's space salesman, selling one-inch ads to small local shops and restaurants... (FMvi-viii)

Thomas N. Armstrong III (Director Whitney Museum 1974-1990, Director Andy Warhol Museum May 1994 for nine months): We now realize that the period from 1958 to 1964 was a critical time of transition in American art, as the unquestioned hegemony of Abstract Expressionism began to flatten and the new movements of Pop Art and Minimalism emerged. (BH8)

[Note: It was mentioned in Armstrong's NY Times obituary that he had been director of the museum for nine months - see William Grimes, “Thomas N. Armstrong III, Museum Chief Who Once Led the Whitney, Dies at 78,” The New York Times, 22 June 2011 g.c.]

Barbara Haskell: Between 1958 and 1964, the arts in America underwent a dramatic upheaval… The onset of this artistic era was publicly heralded in 1958 by two exhibitions in New York, in which Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg presented works incorporating everyday objects and motifs hitherto considered inappropriate for art. In that same year, Allan Kaprow constructed his first environment out of found objects and taped electronic music, and enacted his first public Happening. These presentations reflected the influence of composer John Cage’s theories about the inter-changeability of art and life. Cage’s twenty-five-year retrospective concert in New York in May 1958 and the class he taught that academic year on experimental music composition at the New School for Social Research encouraged a variety of artists from all disciplines to venture into non-narrative and non-traditional forms of performance. Out of these experiences artists evolved fresh paradigms for music, theatre, dance, sculpture, and painting which found expression in Happenings, Fluxus, the Judson Dance Theater, and Pop Art. (BH12)

David Bourdon: ...what was Warhol doing? He was still churning out clever shoe drawings... selling his hand coloured picture books through Serendipity, and providing very little evidence that that he wanted to be taken seriously in the art world. It must have been inconceivable to almost everyone who knew him that a day might dawn when he would be as controversial or famous an artist as Johns, Rauschenberg, or Stella. Compared to that of the probing artists of the New York School, who prized 'tough' and 'authentic' abstract painting, Warhol's work was altogether too facile and ingratiating, unremittingly frivolous, and ultimately irrelevant. (DB66)

Victor Bockris: Meanwhile things were beginning to go badly with Ed Wallowitch. Ed had... moved away from John [Ed's brother] and had his own place. When Ed's sister Anna May [sic] decided to get married he felt deserted and began drinking like a pig and having psychotic episodes. After a while Andy distanced himself from him. Their relationship disintegrated. Ed had a nervous breakdown and had to move back into his brother's apartment, where he stayed on thorazine for six weeks. (VB130)

Tony Scherman/David Dalton: In October 1958, Edward, whose mental state had always been fragile, suffered a severe breakdown. The brothers were broke, and John asked Warhol for a loan to hospitalize Edward, which he refused. (TS27)

John Wallowitch (Ed Wallowitch's brother): The analyst thought it would be better for Edward to go to a place out on Long Island that could handle this kind of thing. But it cost $250 a week. At the time, I was making three dollars an hour and there was no money coming in from Ed, or our parents. I called Andy up and asked him for $600 to help Ed out. He said, 'Oh, I'm sorry. My business manager won't let me do it.' It would be nice if Andy had come to see him or called, but no, there was nothing. I loved Andy, but there was something malevolent and evil about the way he sucked off Ed's energy. But I know Ed got his revenge because Andy took it up the ass a lot. And my brother was well equipped from what I hear. (VB130)

Trevor Fairbrother: During the 1959/60 season, he [Warhol] submitted a group of small oil paintings to the Tanager Gallery, a fashionable artists’ cooperative, for consideration at their monthly business meeting. His friend Philip Pearlstein, who was active in the gallery and present at the meeting remembers that they showed ‘boys kissing boys with their tongues in each other’s mouths.’ They were dismissed because the subject was ‘totally unacceptable… the men in the gallery were all macho… de Kooning was the big dog… the more neutral the subject the better. (TR72)

David Bourdon: In 1959 Warhol produced what would be the last of his privately printed, hand-coloured picture books, Wild Raspberries. (DB67)

Charlie Schieps: Warhol again turned to the pages of the [Harper’s Bazaar] magazine for its December 1959 issue with illustrations for 'Noel Provincial' written by his friend Suzie Frankfurt, with hand lettering by Warhol’s mother. That month the Bodley Gallery exhibited these same drawings with different inedible recipes, calling the show 'Wild Raspberries,' a tongue-in-cheek allusion to Ingmar Bergman’s film Wild Strawberries. This exhibit became a source for a very successful cookbook that remains in print today. (AM4)

David Bourdon: Warhol collaborated on the mock cookbook with designer Suzie Frankfurt who provided the arch recipes for dishes such as 'A & P Surprise,' 'Oysters à la Harriman,' and 'Omelet Greta Garbo.' (DB67)

William Norwich: Born and raised in Malibu - yes, Malibu, Suzie Frankfurt majored in history at Stanford University. She got her first job in New York with the help of her cousin, Norton Simon. She worked in the research department at Young & Rubicam - the ad agency that had the Hunt Foods account, the Simon family business - where she met advertising kingpin Steve Frankfurt, then a promising art director. They married in 1956 and divorced in the mid-1960s. Mrs. Frankfurt began her decorating career redoing Young & Rubicam's offices. (WN)

Suzie Frankfurt: The only reason Andy liked me was because I was raised in Malibu with movie stars like Myrna Loy all around. I liked Andy because I'd always felt my whole life that I was an outsider. It may not be the fact, but it's how I feel. For some strange reason, I felt that I fit in with him... (WN)

William Norwich: Pregnant with her second son, she'd [Suzie Frankfurt] gone to the Serendipity ice cream parlor and restaurant one afternoon. There was an exhibition of “these magical watercolors by Andy.” (WN)

Billy Name: ... in 1959, when I was eighteen... I was working as a waiter in the restaurant Serendipity. Back then it was an elegant and fashionable place, where you could see film stars like Kim Novak. Warhol would usually turn up as the evening began and one of the owners of the restaurant introduced me to him. He wasn't yet famous as an artist, but he already had a name and his first successes in the world of illustration. We were soon on first-name terms. I worked in Serendipity for around a year and Andy came there often. It was there that they first exhibited the Cat books that he worked on with his mother. (RU203)

Steven Bruce (Serendipity owner): When we first opened [in 1954] we created a sort of avant-garde furore because everything we had was Art Nouveau, and it was always considered junk until then… Andy Warhol started coming in – I didn’t know who he was or what he was – and having a coffee or an espresso. Because at that time, we were primarily just gifts and espresso and pastries… And so I would always watch him there drawing, and I didn’t know who he was. He was always carrying around a huge black portfolio – about 20 x 20 – a big, big thing filled with drawings that would come out. And he always wore a sort of sport jacket and pants, and he looked like someone’s poor relative. At that time, he had a very sweet but sad quality, which he still does have – that waiflike quality. And he had troubles with his eyes. He was going to an eye doctor, I found out, for eye tests to strengthen his eyes. And he had a pigment problem with his skin. So, he was very definitely a young man who was gaining his way through the world though his artwork, not because he was a terribly attractive human being, you know, on a very superficial level that people gravitate to. Then he would start, you know, bringing in friends and even at that early age, you know, students that he would have around with, close friends. He would bring them in, and he would have five or six people with him. He would give them work, artwork to finish... (PSC148-9)

William Norwich: Taken by Warhol’s paintings [displayed at Serendipity], she [Suzi Frankfurt] sought him out and, with Mr. Frankfurt as the go-between, arranged to meet for lunch at the Palm Court of the Plaza Hotel in 1959. (WN)

Suzie Frankfurt: We [Suzi and Warhol] had to write a funny cookbook for people who don't cook. My mother, who was a hostess sine qua non, deemed the most important thing for a new bride was to be a good hostess. I wanted to emulate my mother, of course, and it was the year all these French cookbooks came out. I tried to make sense of them. 'Make a béchamel sauce,' they'd say. I didn't even know what that was.

So we did the book, Andy with his Dr. Martin's dyes and Mrs. Warhol [Andy's mother], her calligraphy. She was gifted and untutored, and we left all the spelling mistakes. I wrote the recipes... There were two versions, coloured and semi-coloured. We thought it would be a masterpiece and we'd sell thousands. I think we sold 20. (WN)

Dieter Koepplin: Warhol’s mother did the calligraphic rendering of the recipes… There are also separate versions of other recipe prints, such as the piglet with ribbons and with a rose stuck in its mouth. Here, too, Júlia Warhola wrote the recipes by hand. (DK33)

Martin Warhola (Paul Warhola's son): Granny [Júlia Warhola] gave us the cookbooks that Uncle Andy made in the 1950s. Cook books and colouring books. So we painted and drew in them. We'll always remember how granny would slip a little money into each of them for us. That was very sweet of her. (RU100)

Rainer Crone: The book Wild Raspberries, which was also published in conjunction with an exhibition, makes use of the work of the French cookery writer and illustrator Antonin Carême (1784-1833): Le Pâtissier pitoresque. The pictures in the exhibition and in the book adopt the style of nonsense literature to ridicule the exaggerated faith in recipes and the methods of food preparation preferred by the New York consumer society... [Warhol's] illustrations of recipes and foods [were] doubtless suggested to some extent by Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin's famous La Physologie du gout... According to Nathan Gluck, Warhol submitted this book. This should, however, be seen as a general source of illustrations. (RCA70/109 n. 153)

Nathan Gluck: He [Andy]… bought a few books on elaborate French cooking – where you have these tremendous and elaborate dishes, which the French call presamment and where you have cakes that are built like grottos or huge roasts that are all decorated with things. And those in a sense, prompted... Wild Raspberries, which was a play on words of the Ingmar Bergman movie which was current at the time, which was called Wild Strawberries. And a lot of these drawings were really adapted from them... this one happens to be Careme. But he had a two volume set... I think it was a book called Urban Duboise, La Cuisine classique - the second edition of 1864... or it could have been Dubois and Bernard, which is also La Cuisine classique. That's... 1856. (PS319/334)

David Bourdon: The original [Wild Raspberries) drawings were displayed at the Bodley Gallery in December [1959] and received a favourable one-sentence review in Arts Magazine [in January 1960]. (DB67)

Ted Carey: ... at the same time, Andy was pursuing his fine art career. And Andy first, I think, became interested in pursuing it because I can remember that Andy was spending Saturday afternoons going to the art galleries. And I can remember one day we were in the Museum of of Modern Art, and we went to the art-lending service in the Museum of Modern Art. And there was a collage by Rauschenberg. And it was a shirt sleeve. It was a small collage. It was like a shirt sleeve cut off and that was it. And I said, 'Oh that is fabulous.' And Andy said... well, he said, 'I think that's awful.' He said, 'That's a piece of shit.' And I said, 'I think it's really great.' And he said, 'I think it's awful.' And he said, 'I think anyone can do that. I can do that.' And I said, 'Well, why don't you do it? If you really think it's all promotion. Anyone, you know, can do it!' And so he said, 'Well, I've got to think of something different.' (PS254)