Abstract Expressionism 1942

by Gary Comenas

Serge Guilbaut [from How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art]: "...during the first six months of 1942 the government placed $100 billion worth of orders with the private sector (compared with $12 billion over the preceding six months) and... seventeen million new jobs were created. The demand was such that it was frequently necessary to resort to overtime work and to hire women." (SG90)

1942-43: Adolph Gottlieb serves as Vice-President of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. (AG23/42)

1942: Robert Motherwell marries Maria Emilia Ferreira y Moyers

Motherwell had met the Mexican actress during his 1941 trip to Mexico. Initially they lived on Motherwell's $50 weekly stipend given to him by his father.

Robert Motherwell:

... in one sense I grew up with all the sense of great expectations, went to great universities, had convertibles in college, and so on. And yet in another sense it was all absolutely taken away. So that what people don't realize is that I lived in New York, married, trying to become a painter, having my first show there; I lived there for ten years on fifty dollars a week. And it's been a continual annoyance to me that because of my personal extravagance partly as compensation for all of that that everybody thinks that somehow there are stacks of money around; though actually my success that way has really meant a grater capacity to borrow money when I was younger. (SR)

Prior to going to Mexico Motherwell lived in what he described as "a thing called the Rinelander Gardens which were beautiful old iron-balconied buildings on Eleventh Street. I had a big room and a balcony and the garden in front."

Robert Motherwell:

And then in Mexico I feel in love with a Mexican actress and she came back with me. We took a little apartment on Perry Street for a year, then moved to an apartment on Eighth Street facing MacDougal Street and lived there for several years. Then I moved to east Hampton [in 1945] and built a house with a French architect out of a tiny inheritance my father had left me. I lived in East Hampton for four or five years. Then she and I were divorced [in 1949] and I moved back to New York. I became a professor at Hunter College [in 1950] so then I moved to the upper East side and lived there until just a couple of months ago. (SR)

Early 1942: Barnett Newman asks "What about Isolationist Art?"

The text written by Newman was unpublished at the time. In the document Newman compares American isolationism to Hiterlism and blames the artists for succumbing to isolationism through Regionalism or American Scene painting.

Barnett Newman [from "What about Isolationist Art?"]:

Art in America is an isolationist monopoly. Publishers and critics, art dealers and museum directors, willingly or unwillingly are completely dominated by an isolationist esthetic that permits no deviation... Isolationist painting, which they named the American Renaissance, is founded on politics and on an even worse esthetic. Using the traditional chauvinistic, isolationist brand of patriotism, and playing on the natural desire of American artists to have their own art, they succeeded in pushing across a false esthetic that is inhibiting the production of any true art in this country... Isolationism, we have learned by now, is Hitlerism. Both are expressions of the same intense vicious nationalism... The art of the world, ranted [the isolationists], as focused in the Ecole de Paris, is degenerate art, fine for Frenchmen, but not for us Americans. The French art is like themselves, a foreign, degenerate, Ellis Island, international art appealing to international minded perverts... How could French art be any good anyway? The French people themselves are no good... And who are their American fellow-travelers, a bunch of New York Ellis Islanders who aren't even 50 percent American, most of them Communist and international minded etc. What we need is a good 100 percent American art based on the good old things we know and recognize... the beauty of our land, the traditions of our folk-lore, the cows coming home, the cotton-picker, the farmer struggling against the weather - the good old oaken bucket.... Art in America today stands at a point where anything that cannot fit into the American Scene label is doomed to be completely ignored...

Strangely enough, the American artist fell for this subtle fallacy... So seductive was the isolationist bloc, it didn't mind a bit if the artist stole European painting styles and techniques, so long as they were confined to the American Scene... The result has been the emergence of an ever-expanding school of genre painters who, using borrowed painting techniques, have dedicated themselves to telling the story of America's life of humdrum... Its complete success was marred for a moment by a leftist 'revolt' which thought it had a new esthetic - social painting. But it turned out to be nothing but a variation of the same theme... (TH21/22)

Early 1942: Peggy Guggenheim marries Max Ernst.

Peggy's cousin Harold Loeb and his wife were witnesses at the civil marriage ceremony that took place in Virginia.

(MD220)

January 1942: Barnett Newman applies for conscientious objector status.

Barnett Newman applied for exemption from the draft as a conscientious objector even though he had already been exempted for physical reasons. (MH)

Thomas Hess [from Barnett Newman exh. cat., Tate Gallery, June 28 - August 6, 1972]:

He [Barnett Newman] claimed exemption as a conscientious objector on the grounds that he would be deprived of his "right to kill" as guaranteed under the constitution. He pointed out that although he was happy to kill Nazis, he was not going to kill anyone just because he has been commanded to do so by some lieutenant. They first deferred him on physical grounds but, because of his insistence, then also exempted him from service on the basis of conscience as well. (TH14)

January 19, 1942: Artists' Council for Victory is formed.

Also referred to as The Artists for Victory the Council was a coalition of art groups established by the Artists' Societies for National Defence (see December 17, 1941) which was formed to advance propagandistic art supporting the war effort. (RO156)

January 20 - February 6, 1942: Jackson Pollock shows Birth in "American and French Paintings" exhibition at McMillen Inc.

Curated by John Graham it paired American artists with French artists and included works by Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Andre Derain, Stuart Davis, Walt Kuhn, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock. Krasner exhibited Abstraction. Pollock exhibited Birth (c. 1941). (PP319)

Willem de Kooning:

Graham was very important, and he discovered Pollock. The other critics came later - much later. Graham was a painter as well as a critic. It was hard for other artists to see what Pollock was doing - their work was so different from his. It's hard to see something that's different from your work. But Graham could see it. (DK205)

January 21-March 8, 1942: "Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors sent a protest letter to the museum in February 1942, accusing the them of reducing "American art to a demonstration of geography" and that the museum which "has shown a fine sense of discrimination" in choosing "the very best contemporary European artists," had not "extended the same sense of discrimination" with American Art. (RO158) The letter was reported both in the New York Evening Sun (February 2, 1942, p. 16) and the New York Times (February 3, 1942, p. 21)

January 1942: Macy's art exhibition.

The exhibition included Rothko's myth paintings, Antigone and Oedipus., which were priced at $200 each. (RO160/LF240)

An advertisement for the show appeared in the January 4, 1942 issue of The New York Times. promising "179 canvases by 72 important Americans" priced "with great modesty" at "$24.97 to $249 framed" with works by "many well-known artists!" and "some brilliant discoveries!" (RO160)

The exhibition consisted of seventy artists including (in addition to Mark Rothko) Milton Avery, Ilya Boltowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, Arshile Gorky, Carl Holty, Stuart Davis and John Graham. Prices ranged from $24.97 to $249. (LF240/BA321)

The department store's press release for the show noted that "Macy's presentation of this important exhibit to a larger-than-usual audience, combining the regular gallery visitors with the department store public, constitutes an experiment which may very well determine the future of exhibits of this sort." (LF240)

February 1942: The Federal Art Project becomes part of the War Services Program.

The Federal Art project was reorganized and became a division of the War Services Program. Artists were now assigned to group projects turning out Red Cross armbands, air-raid pamphlets, victory posters. Lee Krasner, as "supervisor of exhibits" oversaw about ten artists, including Jackson Pollock and Peter Busa. She directed a project (with Jackson as her assistant) designing department store window displays announcing war-related training courses. (JP117/PP319)

February 4 - March 10, 1942: U.S. Army Illustrators of Fort Custer, Michigan exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

March 1942: André Breton works for the Voice of America.

Other employees included Claude Levi-Strauss, Klaus Mann, Yul Brynner, Robert Lebel, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Denis de Rougemont, Georges Duthuit, Julien Green, and André Maurois.

(SS20/)

Denis de Rougement:

[Breton] would appear at 5 a.m. at the end of a large room, supremely courteous and with the patient air of a lion who has decided to ignore the bars of his cage. He lent us his noble voice but he kept for himself his tinge of irony and solemn carriage... He held success at arm's length, leaving it to Salvador Dali to make money out of a movement even more prestigious here than in Paris: Surrealism. (SS222)

March 3 - March 28, 1942: "Artists in Exile" exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York

Artists in Exile: Front row left to right: Matta Echaurren, Ossip Zadkine, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, Second row: André Breton, Piet Mondrian, André Masson, Amédée Ozenfant, Jacques Lipchitz, Pavel Tchelitchew, Kurt Seligmann and Eugene Berman. (Photo: George Platt Lynes/WR5)

Fourteen artists were represented with one piece each: Matta, Ossip Zadkine, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, André Breton, Piet Mondrian, André Masson, Amédée Ozenfant, Jacques Lipchitz, Pavel Tchelitchev, Kurt Seligmann and Eugene Berman. (JR201)(Edward Alden Jewell, "Noted Exiles' Art on Exhibition Here," The New York Times, March 7, 1942, section: society-art, p. 20)

Pierre Matisse [from a letter to his father, the artist Henri Matisse, dated March 1, 1942]:

I stayed in town to hang the exiles' show today, instead of tomorrow. I took this precaution because all the exhibitors are right here in town. You know what they are like. They'd insist on giving me advice, and making sure that their own painting had a very good place. There is Ozenfant, whom I knew in the last war, Léger of course, and Chagall, Lipchitz, Masson, Zadkine, Tanguy, André Breton (who has sent in a poem-object), and Mondrian, abstraction's holy man. They number fourteen in all, and I got them together for a group photograph. As most of them didn't speak to one another when they were in France, I was afraid there would be trouble when they were all thrown together. But, as you can see from the enclosed photograph, all went well. (JR201)

In his preface to the exhibition catalogue (which also included an essay by Nicholas Calas), James Thrall Soby indicated two possible directions for American Artists - either the acceptance of a "new internationalism" or a "xenophobic" reaction against the exiled artists ("and wait for such men to go away leaving our art as it was before.") Soby, of course, backed a new internationalism.

James Thrall Soby [from the catalogue preface]:

Fortunately, numbers of of American artists and interested laymen are aware that a sympathetic relationship with refugee painters and sculptors can have a broadening effect on native tradition, while helping to preserve the cultural impetus of Europe. These Americans reject the isolationist viewpoint which 10 years sought refuge, and an excuse, in regionalism and the American scene movement. They know that art transcends geography.... (SG64)

The topic of a new internationalism was also taken up by Samuel Kootz when he wrote the text for the catalogue of a Byron Browne show at the Pinacotheca Gallery the following year (March 15 - 31, 1943).

Samuel Kootz [from the catalogue of the Byron Browne show]:

America's more important artists are consistently shying away from regionalism and exploring the virtues of internationalism. This is the painting equivalent of our newly found political and social internationalism. Byron Browne is making a personal contribution in this field through energetic inventions, brilliant color dissonances and athletic rightness in space divisions. His balanced designs and rhythms are highly rewarding and repay continuous investigation. In an area not yet familiar to most of the American public. Byron Browne is rapidly succeeding in crating a fine place for himself. His aggressive grasp of our more advanced ideologies pays off in canvases that evidence constant growth. (SG70-71)

March 31 - April 21, 1942: Matta has his first solo exhibition in the U.S. at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

Among the works exhibited were Rain, The Earth Is a Man and Locus Solus.

The Earth Is a Man, which incorporated Matta's technique of sponging on and wiping off thinned pigment to produce translucent layers of colour, was inspired by Matta's trip to Mexico in 1941 with Robert Motherwell. James Thrall Soby wrote that Locus Solus was the beginning of Matta's attempt for "a sterner architonic order" with lines intercepting his amorphous forms. (SS210-11)

James Thrall Soby [from "Matta Echaurren," Magazine of Art (March 1947), p. 104]:

In a number of canvases painted in 1941 and 1942, Matta pierced his thin sprays of color with triangular or rectangular corridors, white, solid, heavily lined, leading past walls of lame or cutting through banked mists of rose, yellow and blue. (SS211)

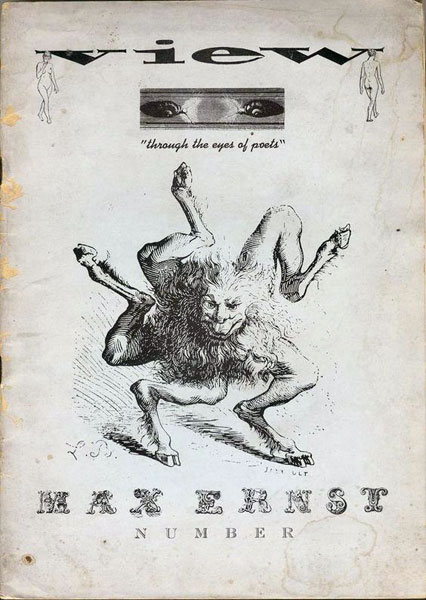

April 1942: André Breton discusses myths in the Max Ernst issue of View magazine.

The Max Ernst issue of View magazine

The issue included Lionel Abel's translation of Breton's "The Legendary Life of Max Ernst: Preceded by a Brief Discussion on the Need for a New Myth." (Reproductions in the issue included work by Joseph Cornell, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst and James Thrall Soby." (VP273)

Spring 1942: James Johnson Sweeney visits Jackson Pollock's studio.

Herbert Matter invited him to see Pollock's work. After his visit, Sweeney told Peggy Guggenheim that Jackson was doing interesting work and suggested that she visit his studio. (PP319)

Other visitors around this time to Pollock's studio were Alexander Calder and Hans Hofmann. Hofmann lived in the building next door to Pollock's studio so Lee Krasner invited him over to hear what he thought of Pollock's work. Hofmann told Pollock "You are very talented. You should join my class." He asked Pollock if he worked from nature. Pollock replied, "I am nature." (JP116)

Spring 1942: Jackson Pollock's mother visits Jackson and Sande in New York.

On May 5, 1942, Pollock's mother Stella wrote to her other son, Charles: "Tuesday night almost ten o'clock Jack & I washed the dishes read a while and listened to the radio, he has just left for his girls [Lee Krasner's] home." (JP117)

Spring 1942: Wolfgang Paalen launches Dyn.

Dyn, written in French and English and published in Mexico, was geared to a New York audience (ads included the Gotham Book Mart). Paalen announced his resignation from Breton's group of Surrealists in an essay in the first issue, "Farewell to Surrealism." He hoped to establish a new group which would be "beyond Surrealism." Five issues of Dyn were published over the course of its life - the last issue was published in 1944. Jackson Pollock had all five issues. (SS212/267)

April 8 - May 16, 1942: Franz Kline exhibits at The National of Academy of Design's Annual Exhibition.

241 paintings (one per artist) were exhibited at the Academy's galleries at 1083 5th Avenue. The works were chosen from 1,300 submitted. Kline showed Artist's Wife, priced at $200. ("Academy of Design Opens Its Art Show," The New York Times, Section: "Society," P. 15.)

May 1942: Harold Rosenberg writes about myth in the Tanguy/Tchelitchew issue of View magazine.

Alternate pages of the magazine were printed upside down so that both the front page and the back page could be viewed as covers. One cover featured Tanguy and the other Tchelitchew (aka Tchelitchev.) Articles included "Breton - A Dialogue" by Harold Rosenberg in which three intellectuals discussed the need for a new myth and also an article on Tanguy as an "iconographer of Melancholy" written by James Johnson Sweeney. (SS219/VP46/273)

James Johnson Sweeney [from "Tanguy, Iconographer of Melancholy"]:

"In Yves Tanguy we have Surrealism's iconographer of melancholy... The dream character and melancholy note are products of his color handling and the disposition of compositional elements in the great lonely spaces of his canvas... He sets the stage and we dream onto it. For essentially Tanguy's art is an abstract art in the sense that his forms have been stripped of familiar individualizing resemblances to objects in the world of nature... The haunting emptiness of space and of far horizons is effected by a subtle modulation of tones, rather than by evident perspective lines. The mood is set by the dominant grays, blues and violets of the artist's palette. Suddenly the barrier between us and the picture melts and we find ourselves building our own interpretation of the stripped forms, colored only by the melancholy note which the painter had carried always with him from the bare landscapes of his youth." (VP47-8)

May 1942: Alexander Calder exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

E.A.J. [presumably Edward Allen Jewell] wrote in The New York Times, "That irrepressible and brilliantly imaginative playboy of the art world, Alexander Calder, is back again, with a fresh assortment of 'mobiles' and 'stabiles' shown to advantage in the breeze-swept Pierre Matisse Gallery... Calder continues gaily and charmingly to titillate the nonobjective." (E.A.J., "Among the Local Shows," The New York Times, May 24, 1942 (Sunday), p. x5)

May 1942: Second annual exhibition of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors at the Wildenstein Galleries.

Adolph Gottlieb exhibited a Pictograph painting (Symbol) for the first time at the exhibition.

(AG39)

May 1942: The Museum of Modern Art acquires Arshile Gorky's Garden in Sochi (1941). (MS241)

Alfred Barr paid for the work by returning Gorky's Khorkum (c. 1938), which the Schwabachers had donated to the museum, and paying out an additional $300. (BA325) In June 1942 Dorothy Miller (then the assistant to Alfred Barr) asked Gorky to contribute a statement about the painting for the museum's files. The statement began, ""I like the heat the tenderness the edible the lusciousness the song of a single person in the bathtub full of water to bathe myself beneath the water. I like Uccello Grunewald Ingres the drawings and sketches for paintings of Seurat and that man Pablo Picasso." (MS242) Gorky makes no direct reference to the painting in his statement, which is mostly a poetic description of the "Garden of Wish Fulfillment" from Gorky's childhood (as quoted in "Arshile Gorky's Childhood").

May 6-June 16, 1942: Art Sale for the Armed Services at The Museum of Modern Art.

c. Spring - Autumn 1942: Julien Levy serves in the Army.

Julien Levy:

I was soon in the army, my gallery closed. Between closing my gallery and entering the Army in 1942, I was at Durlacher's, where my friend Kirk Askew allowed me to give my own shows... Much of my service in the Army was spent in hospitals with a mysterious malady - of the thyroid glands... Entering the Army, and my prolonged illness, interrupted my participation in the events of the New York art world for a period which was to prove of much significance for subsequent decades... The following events took place: the mingling of the exiles from Paris with the New York artists; the installation by André Breton with the advice and collaboration of Marcel Duchamp of a large Surrealist show in New York; the debut of the magazine VVV, edited by Breton and David Hare; and, most important of all, I feel, there began the extensive dialogue between Arshile Gorky and André Masson in Roxbury, Connecticut, and later of Gorky with Matta. Another event was the opening of Peggy's gallery, Art of This Century, which rocked New York with the violent drip paintings of Pollock. (MA259)

Levy's comments about missing out on so much give the impression that he was in the Army longer than he was. Judging from the exhibition list of his gallery included at the back of his book, Memoir Of An Art Gallery, he probably served for about four months - between the closing of a Pavel Tchelitchew exhibition on May 18, 1942 and the opening of a Maud Morgan show on October 13, 1942. And much of the time that he served in the Army was spent in Manhattan. He notes, "Not long after my Army Corps basic training in Florida, I was assigned to a school for mechanics in Manhattan, of all lucky places." (MA259) Several pages later he discloses that he was honourably discharged for medical reasons "in time for Thanksgiving" 1942. Although he may still have been recovering from his illness at the time he notes that his thyroid condition, which "for some obscure military reason" could only be treated by civilian doctors, was "straightened out" by his New York doctor and he "returned to normal," adding that "the cure consisted of carefully exact doses of thyroid extract, to be taken the rest of my life." (MA261)

May 21 - October 4, 1942 Road to Victory exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition attracted 98,000 viewers. (SG89) Edward Alden Jewell reviewed it for The New York Times.

Edward Alden Jewell:

The supreme war contribution... was the magnificent 'Road to Victory' at the Museum of Modern Art... Composed of striking photographs, many of them enlarged to full mural dimensions, this veritable portrait of America was created by Lieut. Comdr. Edward Steichen and Carl Sandburg, working in collaboration. Their achievement, heroic in stature, I have already characterized as the season's most moving experience. (SJ)

The exhibition was designed by Herbert Bayer who had previously been one of Hitler's team of architects and would go on to marry Julien Levy's ex-wife Joella Haweis in 1944. (BA336/SG88)

May 1942: Peggy Guggenheim publishes a catalogue of her collection.

2,500 copies of the book were published which included photographs of the eyes of the artists next to their works and a selection of artists' statements. It featured a cover by Max Ernst and was printed partially in green ink, the color that Breton often used for his writings. Breton's essay "Genesis and Perspectives of Surrealism" was included.

André Breton [From "Genesis and Perspectives of Surrealism"]:

Automatism is the only mode of expression which gives entire satisfaction to both eye and ear by achieving a rhythmic unity... there is a grave risk, however, that a work of art will move out of the Surrealist orbit unless, underground at least there flows a current of Automatism. The Surrealism in a work is in direct proportion to the efforts the artist has made to embrace the whole psycho-physical field, of which consciousness is only a small fraction. (SS213)

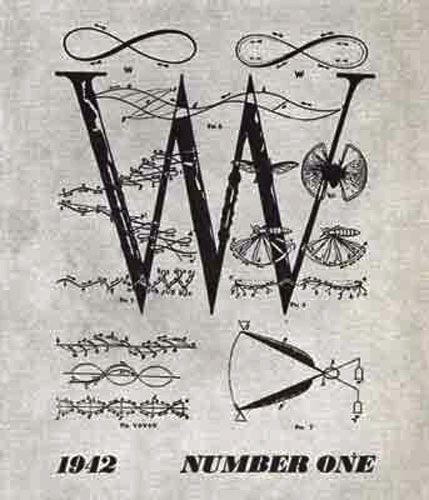

Late Spring/Early Summer 1942: The first issue of VVV magazine is published.

First issue of VVV magazine

Only three issues of the magazine would be published beginning with the spring 1942 issue. In a letter dated either May or June 1942, Matta wrote to Gordon Onslow Ford, "This winter in New York was a very hot one - all energies were lost in personal quarrels. I was fighting most of the winter for the publication of VVV; now it is at the printer's. André at full strength - sabotage of all the click around View (Calas, Seligmann, etc.). Abel, the editor, wrote a very clear program."

(SS214)

Robert Motherwell:

I'll tell you what I remember - and there's a lot I don't remember... The Surrealists were proselytisers... They very badly wanted a vehicle here. By hook or by crook slowly some money was raised. The actual editor was André Breton who always was the chief of everything Surrealist. I think Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst if I remember were associate editors. But the Surrealists had a feeling - not really realizing that artists in America are not taken very seriously - that they were politically radical, etcetera, they were aliens, exiles, etcetera, and that ostensibly there should be an American editor. There was also some effort to get some Americans to contribute. William Carlos Williams and so on.

And so for a time I accepted the role simply to help them out. Then one day it became clear to me in an angry discussion in French, which I only partly understood, that they had also assumed that I had American connections and could raise some money. Which I didn't have, and couldn't. Then I got furious and resigned. And the compromise was that Lionel Abel and I co-edited. And then what transpired was that Abel, who had no job, no money, no anything, asked for the colossal sum of twenty-five dollars a week simply in order to exist while he was gathering the manuscripts and all the rest of it. And again, they got furious at that and fired him. Then I said, "I resign." Then David Hare who had, I think, an independent income agreed to be the nominal editor.

Something very interesting to me that always amuses me is how the name VVV came about. They wanted to invent a twenty-seventh letter in the alphabet. In French the letter W is double V (VV). And so they hit on the idea of having triple V (VVV) as the twenty-seventh letter. And Breton also didn't know a word of English. And as sort of their American adviser, lieutenant, liaison officer, I pointed out to him that for reasons I didn't understand double V in English is pronounced double U so that it would not translate; in English you would have to call it triple U when nevertheless the sign was three V's and it really wouldn't work. He would not accept that it wouldn't work. And it used to confuse everybody. People didn't know whether to say V-V-V or triple V or triple U or whatever. But if it were literally transcribed into English the proper title would have been triple U. And the fact that they chose V with the way that English-speaking people say V made it not translate. Well, if you said triple U the name of the magazine immediately Americans would have got the point. But it was always called triple V and nobody got the point. It seems senseless. (SR)

Not everyone was impressed by the first issue. In a letter to Meyer Schapiro, Kurt Seligmann wrote: "The only qualification I can find for that issue is lousy." (SS219)

Onslow Ford [from a draft letter to Matta, June 1942]:

... apart from Andre's magnificent article, I find it rather difficult to get the direction that VVV is taking. Why were you and Bob not front page? Why was there no mention of Estaban? Why should corpses be imitated instead of trampled upon? Or maybe I misunderstood Abel's introduction. Anyway, best of luck with the next number. you can afford to be tough as they cannot do without you. (SS219)

Summer 1942: Max Ernst drips.

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

There was... according to Ernst, one work, shown later that year by Betty Parsons at the Wakefield Gallery, that intrigued several of the American painters because of its unusual technique. With the benefit of hindsight, he recounts in his 'Biographical notes - tissue of truth, tissue of lies' how he told them it was child's play. 'Tie a piece of string, one or two meters long, to an empty tin can, punch a small hole in the bottom and fill the tin with thin paint. Then lay the canvas flat on the floor and wing the tin backwards and forwards over it, guiding it with movements of your hands, arms, shoulders and your whole body. In this way surprising lines will drip onto the canvas. Then you can start playing with free associations.' ...Whether or not he actually said those words in 1942 is immaterial; the works themselves were evidence of the process and Ernst could also be seen that summer on Cape Cod swinging a paint can over a canvas spread out on the kitchen floor. (SS207)

It is unknown which work is being referred to in the above the quote. However, Howard Devree in The New York Times reviewed a group show at the Wakefield Gallery and Bookshop in June 1942 which refers to an Ernst painting on exhibit as "a disconcerting composition" made up of "seemingly dissociated soup bones," but no mention of drips. (Howard Devree, "A Reviewer's Notebook," The New York Times, June 28, 1942 (Sunday), section: Drama, Screen, Music, etc..., p. x5)

Early Summer: Franz Kline works for the Army.

Kline worked as a filing clerk for the U.S. Army on Governors Island. Kline would later draw a caricature-like portrait of the wife of Col. S.G. Backman, quartermaster for the Third Corps Area. It was through Backman that Kline got the job. Although he only worked for a few weeks he would later recall it as six months. (FK177)

Summer 1942: Robert Motherwell spends the summer in Provincetown, Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

It was the first of many summers he would spend there. (RM131)

June 1942: Arshile Gorky visits his in-laws in Washington, D.C.

While there he saw Ingres's Odalisque with Slave at the Walters Art Gallery. (BA327)

Summer 1942: Jackson Pollock stops seeing Dr. Violet de Laszlo. (JP145/pp320)

As de Laszlo was not having much success in keeping Pollock off the booze, Lee Krasner thought the expense wasn't worth it. Dr. de Laszlo later recalled, "Lee was very possessive and so she was threatened by anyone else on whom he was dependent." (JP145) In the autumn of 1944 Pollock would start seeing Krasner's homeopathic doctor, Elizabeth Wright Hubbard. (PP321)

Summer 1942: Arshile Gorky sketches a waterfall in Connecticut.

In addition to visiting his in-laws in Washington, D.C. in June, Gorky also stayed at Saul [in some sources spelled "Sol"] Schary's home in New Milford, Connecticut for two or three weeks during the summer. While there, Schary took him to see a nearby waterfall. Schary loved "to go down there and paint." Gorky fell in love with the spot as well and did drawings of the waterfall.

Saul Schary:

I took him down to a ruined mill on the Housatonic River... The Connecticut LIghting Power Company had gotten control of all the water power and anybody who had a mill couldn't use the water power, so these mills were abandoned. Over the years it feel into ruin until it was a really handsome and romantic ruin. Just below where they took the power was a waterfall. I used to love to go down there and paint. (BA329)

Schary recalled that after he showed Gorky the waterfall, Gorky "wouldn't come out of that water. He loved it so. In reminded him of a spot back home. He just stood on the rock and let the water flow past him." (BA329)

Gorky would paint his fully abstract work, Waterfall (now in the collection of the Tate Modern in London), the following year - in 1943. Schary kept the first sketch Gorky made of the Housatonic River waterfall in 1942 and later recalled that it was "more realistic than his Waterfall [painting]." According to Schary, the drawing (which was later sold to Joseph Hirshhorn), "shows very clearly how" Gorky's Waterfall painting "evolved out of the water falling over the rocks and splashing up and making these strange kinds of forms." (BA329)

Arshile Gorky, Waterfall, 1943, Tate Museum of Modern Art (London), 1537 x 1130 mm

There was also a waterfall at the home that the Gorkys moved into in September 1945 and lived in until Gorky's death in 1948 - the Hebbeln glass house. A neighbour of the Hebbeln house, the Magic Realist artist Peter Blume, later recalled that he thought Gorky "had sort of a profound interest in the waterfall." (HH611)

The Gorkys also spent time at Crooked Run Farm in Virginia owned by the parents of Gorky's wife. The Waterfall painting has been attributed to 1943 and the Gorky's stayed at Crooked Run from about late May/early June to October 1943. (MS261) Although descriptions of the farm do not include a waterfall, there was a river there which "fascinated" Gorky.

From From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky by Matthew Spender (who later married Gorky's daughter Maro):

... he [Gorky] was fascinated by the river. In May, Crooked Run Stream would have been a robust rivulet containing the occasional languid trout, but when the weather warmed up it sank to a brackish trickle above which hovered thousands of mating midges. The cows wandered down to watch Gorky working in the deep pasture. Ladies, he would say politely, can you please move away? The cows, impervious, remained... He tried reciting Mayakovsky to them at the top of his voice to scare them off. No luck. They liked Mayakovsky. (MS255)

While visiting Schary, Gorky may have also painted The Pirate I. According to Martica Sawin in Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School, Gorky painted Pirate I when "he was staying at the home of Sol Schary in New Milford, Connecticut." (SS210) Sawin notes that "this painting consists largely of pale washes of runny paint delicately touched with passages of the fluent line drawing that was to become the quintessential Gorky." (SS310) According to Gorky's later art dealer, Julien Levy, however, the work was based on a mongrel dog called "Old Pirate" who appeared in Gorky's yard. This is unlikely given that Gorky was still living in the city in 1942 and didn't have a yard, as Hayden Herrera points out in Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work (HH599)

During his stay at the Scharys' place, Gorky also visited André Masson who lived in New Preston, Connecticut. Masson's son, Diego, recalled Gorky visiting their home. Masson would later say that Gorky was the only American painter that he knew. (Masson returned to Europe in 1945.) (SS211)

June 1942: Peggy Guggenheim stays in in Cape Cod.

Peggy initially stayed in Wellfleet with her daughter, Pegeen, and Max Ernst but then moved to Provincetown where they shared a house with Matta who had been living there since May 1942. (SS220) The landlord of Matta's residence, John Phillips, recalled visiting the property and seeing Max Ernst dripping paint on to a canvas from a can.

John Phillips:

Problems with the electric generator took me over there frequently. They were very theatrical. They made me nervous, but they weren't boring. They wanted to project something by the way they walked, talked, and looked. I had the impression that they weren't thinking much outside the perimeters of their own emotional stuff. All the jokes were in-jokes. I think my wife joined in some of the games they were always playing. Peggy Vail [Guggenheim] was doing transformations of bottles and I remember Max Ernst swinging a can of paint with holes punched in the bottom over a canvas spread on the kitchen floor. David Hare was there cavorting with Jacqueline Lamba on the beach. Matta used to go about with a little walking stick and a kerchief. It thought he was absolutely riveting, full of energy and very friendly. Matta did a lot of painting up there and Motherwell who arrived looking very grey flannel suit seemed very impressed by his work. (SS220)

Because Ernst had failed to inform the authorities of his change of residence and because there was a shortwave radio where Matta was staying, Ernst was questioned by authorities who suspected him and Matta of espionage. Max evaded imprisonment (with the help of Bernard Reis and a Boston district attorney who had previous dealings with the Guggenheim family) and returned to New York with Peggy . (MD225/RO182)

June 25, 1942: Marcel Duchamp arrives in New York. (MB237)

Left to right front: Stanley William Hayter, Leonora Carrington, Frederick Kiesler, Kurt Seligmann, Middle: Max Ernst, Amedee Ozenfant, Andre Breton, Fernand Leger, Berenice Abbott, Back: Jimmy Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim, John Ferren, Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian

(Photographer unknown (MB))

It would be Marcel Duchamp's seventh trip to the United States. The previous trips had taken place as follows:

1. June 15, 1915 - August 13/14, 1918.

Departed from Bordeaux on the S.S. Rochambeau on June 6, 1915. Arrived U.S. June 15, 1915.

Departed from New York on August 13 or 14, 1918 on the USS Crofton Hall bound for Barbados and Buenos Aires.

After living in Buenos Aires Duchamp left Argentina on June 22, 1919. After a three day stopover in London he arrived in France on July 26, 1919 and stayed mainly in Paris until December 27, 1919. (MB109/137/TD39/70/89)2. January 6, 1920 - June 9, 1921. (TD98)

Departed from France December 27, 1919 on the "Touraine" from Le Havre to New York, arriving January 6, 1920. (TD90)

On June 9, 1921 he boarded the "France" for Le Havre, arriving at Le Havre on June 16, 1921. (TD98/MB147/162)3. Early February 1922 - February 10, 1923.

Departed for the U.S. aboard the S.S. Aquitania on January 28, arriving about a week later. (TD105/MB165)

Departed from the U.S. on the "Noordam" to Rotterdam on February 10th, settling in Brussels until he returned to Paris in July 1923. (TD129/132/MB168)4. Late October 1926 - February 26, 1927. (TD159/131)

Duchamp boarded the "Paris" in Le Havre on October 14, 1926. (TD157)

On February 26, 1927 he returned to France on the same boat - the "Paris" - that he had arrived on. (On board with him was Julien Levy.) (TD160)5. Early November 1933 - January 20, 1934. (TD161/185)

Departed for the USA on the "Ile de France" on October 25, 1933.

Departed from the USA on the "Champlain" on January 20, 1934.6. Late May 1936 - September 2, 1936. (TD185)

Departed for the USA on the "Normandie" on May 20, 1936.

Departed from the USA on the "Normandie" on September 2, 1936.

For his 1942 trip to the U.S. Duchamp had started the process of getting out of France about two years prior to his departure. On August 22, 1940 his friend and patron Walter Arensberg officially invited him to America. (MB234). On September 30, 1940 Duchamp wrote to Arensberg "Can you do the necessary in Washington for them to give me a visa for 6 months? - to be sent to the American Consulate in Marseilles. Reasons: definite commission for a decoration. guaranteed income for 6 months, signed and witnessed." (TD224) By November Arensberg informed Duchamp that immigrating to America would be a better option than arriving on a visitor's visa and sent Duchamp the required affidavit for immigration. Duchamp received the affidavit by the end of the month but it wasn't until six months later, on July 3, 1941, that he presented it to the American Consulate in Marseilles. He was told that he was two days late - as of July 1st, the rules had changed meaning that two guarantors were now required for immigration. Arensberg tried to get Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the director of The Museum of Modern Art, to intervene without success and also approached George Biddle who he had met at a dinner and whose brother Francis was the attorney general. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Arensberg, Katherine Dreier was also trying to get Duchamp out of France. Finally, in mid-May of 1942 Duchamp sailed for Casablanca from Marseilles where he hoped to get a plane to LIsbon. He eventually arrived in New York on June 25, 1942 on the Portuguese boat, the Serpa Pinta. (MB237)

After arriving in New York Duchamp initially stayed at the apartment of Robert Allerton Parker and his wife Jessica Daves. After about a month he moved into Peggy Guggenheim's home, Hale House, while Guggenheim was staying in Cape Cod and Provincetown. From October 2, 1942 - October 1, 1943 he rented a room in Frederick Kiesler's penthouse apartment. After his rent was up at the Keisler penthouse he rented his own studio, beginning in October 1943, at 210 West 14th Street which he would continue to rent for the next 23 years. (TD229/237/SS220-2/MB245)

Summer 1942: Arshile Gorky's wife, Agnes finds out she is pregnant. (BA328)

Gorky and Agnes stayed at Saul Schary's home in Connecticut during two weeks in the summer. Schary took Gorky to see a ruined mill on the Housatonic River where Gorky produced numerous drawings. At one point Gorky asked Schary if he should have another baby and Schary told him he couldn't afford it. Unknown to Schary, Gorky and Agnes had recently found out she was pregnant. Gorky was incensed by Schary's advice and their friendship cooled. (BA330)

Raphael Soyer painted a portrait of Agnes when she was pregnant. After the sessions Soyer served dinner and David Burliuk (who had completed some sketches of Gorky in 1941) sometimes joined them. Architect Serge Chermayeff who, like Soyer was a Russian emigre, was another guest. (BA337)

June 30 - August 9, 1942: "New Rugs by American Artists" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

One of the rugs "Bull in the Sun" was designed by Arshile Gorky who told Dorothy Miller at MoMA, "The design is the skin of a water buffalo stretched in the sunny wheatfield. If it looks like something else then it is even better!" (BA327)

August 1, 1942: Arshile Gorky receives his draft papers.

Gorky wrote to his sister Vartoosh on August 2, 1942, "Yesterday I received my papers from the draft to fill in, but I don't know what class they'll put me in 1A 2B 3A I don't know yet." (HH568) When he arrived at the draft office he was examined by a cross-eyed doctor who reminded him of a Chaim Soutine portrait. According to Gorky biographer Hayden Herrera, he was rejected by the draft because he was overage. (HH568) He was also "4F". Peter Busa later recalled that Gorky came over to his apartment right after being examined by the doctor and told him that "The doctor said I'm 4F." When Busa told him that that meant he didn't have to go into the army, Gorky said "Is it really so good? Maybe there's something wrong with me" and spent the rest of the morning discussing whether the doctors knew something that he didn't. (HH568)

August 12 - September 13, 1942: "Camouflage for Civilian Defense" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

August/September 1942: Lee Krasner moves in with Jackson Pollock.

Pollock's brother, Sande, his wife Arloie and their daughter Karen moved to Deep River, Connecticut, leaving Jackson with the apartment on East 8th Street. Pollock's mother, Stella, who had been staying with them, went with Sande and Arloie to Connecticut. After they left Lee Krasner moved in with Jackson. (JP/PP319)

Autumn 1942: Robert Motherwell meets Jackson Pollock.

Robert Motherwell met Jackson Pollock while he was organizing the gatherings at Matta's apartment (see below). When Matta and Motherwell were deciding on participants, William Baziotes suggested to Motherwell that Pollock would be a good addition to the group and suggested that Motherwell visit Pollock in his studio at 46 East 8th Street. (JP123) (According to the Jackson Pollock chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art Pollock was brought into the fold of the Surrealists after attending a dinner party at Matta's apartment. (PP319))

Motherwell's first impressions of Pollock were of a "deeply depressed man," who "was so involved with his uncontrollable neuroses and demons that I occasionally see him like Marlon Brando in scenes from A Streetcar Named Desire - only Brando was much more controlled than Pollock." (JP121)

Autumn 1942: Matta practices automatism with Abstract Expressionists.

Robert Motherwell helped Matta organize workshop type gatherings at Matta's apartment where the Surrealist technique of "automatism" was explored - a sort of painterly version of stream-of-consciousness writing where a painter painted instantly and automatically with the hope of achieving as sort of purity of abstraction not linked to subject matter - similar to what Pollock later achieved through his "drip" paintings.

Robert Motherwell:

The real thing started when Matta who had an oedipal relation with the Surrealists - he both loved them and hated them - and was younger, he was my age - which is to say we were in our twenties - and they were in their forties. Matta wanted to start a revolution, a movement, within Surrealism. He asked me to find some other American artists that would help start a new movement. It was then that Baziotes and I went to see Pollock and de Kooning and Hofmann and Kamrowski and Busa and several other people. And if we could come up with something Peggy Guggenheim, who liked us, said that she would put on a show of this new business. And so I went around explaining the theory of automatism to everybody because the only way that you could have a movement was that it had a common principle. It sort of all began that way. I realize now - and I don't mean this cynically - I was naive. I realize now that most of the interest of the other artists was not in the principle of automatism so much as in the fact that I had a connection with Peggy Guggenheim...

[Automatism] was a Surrealist technique but it had all kinds of possibilities... Klee used that kind of technique, although he was not really a Surrealist; Masson and Miro and Arp were all doing it... You see, what I realized was that Americans potentially could paint like angels but that there was no creative principle around, so that everybody who liked modern art was copying it. Gorky was copying Picasso. Pollock was copying Picasso. De Kooning was copying Picasso... I was painting French intimate pictures or whatever. And all we needed was a a creative principle... And I thought of all the possibilities of free association - because I also had a psychoanalytic background and I understood the implications - might be the best chance to really make something entirely new which everybody agreed was the thing to do.

... Ultimately Gorky got drawn into the Surrealist camp; also David Hare, and Noguchi who was in love with Matta's wife at that time. People nowadays have very little sense of how little intermingling there was. I mean everybody now knows that the European artists in exile were here during the war and they all assume that these artists were everywhere and that everybody saw them. It wasn't that at all. The Europeans mainly saw The Museum of Modern Art people and society people, not especially because they wanted to but they were sort of taken in hand that way... (SR)

According to the Jackson Pollock chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art, Matta was "interested in breaking from the Surrealist movement in America" which was "controlled by André Breton." Although Jackson Pollock participated in the gatherings, he became "frustrated with the group" which was disbanded by "late winter." (PP(319) (Note: The MoMA chronology indicates that Matta's apartment was on 9th Street whereas it is located on 12th Street in Jackson Pollock: A Biography by Deborah Solomon. (JP123)

From Jackson Pollock: A Biography by Deborah Solomon:

Pollock rarely talked at the weekly gatherings... Once Matta asked each of the artists in the group to give a definition of a flower. "A flower is a fox in a hole," Pollock said, and although no one was quite sure what the comment meant, its ambiguity only heightened its value. Another time Pollock stared for a few moments at the smoke rising from his cigarette. Which is the empty space, he wondered aloud, the smoke of the air? Pollock was interested in Matta's theory of "psychic morphology," which maintains that forms, like feelings, are constantly undergoing change. Once Pollock mentioned that a good example of this theory could be found in Navaho art, where men step out of their skins to become thunderbirds. Motherwell started to elaborate on the subject, but Matta quickly silenced him. "The reason Jackson is successful," Matta said, "is because he doesn't talk too much." (JP123-4)

Solomon also mentions that "Surrealist parlor games" were played at the sessions such as "Male and Female" where a sheet of paper was passed around the group and each artist added something to it, resulting in androgynous fantasy figures. (JP124) Jackson Pollock's Male and Female (c. 1942), was possibly named after the Surrealist game.

c. Mid-1942: Arshile Gorky applies unsuccessfully for a job at Brookline College, Massachusetts.

Gorky's failure to get the job left him and his wife, Agnes, in a desperate financial state. Although Agnes came from a privileged background, her parents had cut her off financially because of her support of Communism. Ethel Schwabacher, who Gorky taught privately (and who would later write one of the first biographies of the artist), and her husband, would invite Gorky over for dinner. Gorky's wife Agnes recalled that they were so hungry at the time due to their financial situation that " We just hoped they would pass the steak twice. They were awfully sweet. 'Oh is that steak?' we would say. Sometimes there wasn't enough to go around twice." (BA327)

October 1942: Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock study sheet metal.

When Krasner and her team finished the window-display project (see February 1942), she was given a new assignment designing posters for navy recruiting centres. (PP319) According to the Deborah Solomon biography of Jackson Pollock, "In October Pollock and Lee were both assigned to a vocational school in Brooklyn - to learn how to manufacture aviation sheet metal. A week after Pollock started school he was ordered back to Manhattan to rejoin the War Services program. " (JP127)

October 1942: Marc Chagall exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery.

From Time magazine [October 26, 1942]:

A cosmopolitan crowd of Manhattan art-lovers trampled each other's elegant toes last week to see an exhibit of paintings by Marc Chagall, one of the least known (in the U.S.) of important modernist painters, the man for whom the word Surrealist was first coined...Today Marc Chagall says of Surrealism "Not for me." A hater of realism as well, he refuses to be joined by any artistic school. He will not even discuss his own work. "Monsieur," he says in his dense Vitebsk French (he speaks no English), "l'art est comme l'amour. If your wife is ugly, you do not talk about her looks. If she is beautiful, they speak for both her and you."

October 1, 1942: Mark Rothko's wife's jewelry appears in Vogue magazine.

The short blurb in Vogue on her increasingly successful jewelry business noted "...because they are hand-made, because they are sterling silver, you will want these for your own./Order them by mail from Edith Sachar, 29 East Twenty-Eighth Street. The curling leaf pin, $4.50, the graceful ear-clips, $3.75 a pair..." (RO169)

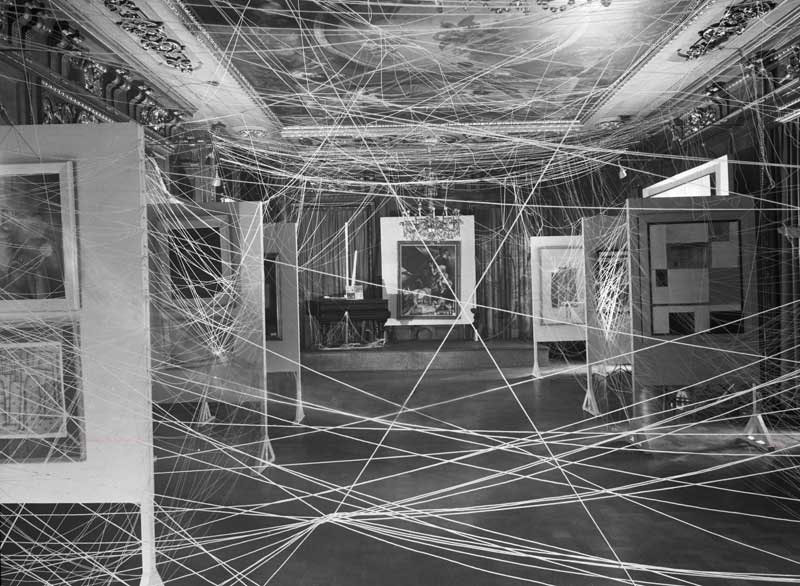

October 14 - November 7, 1942: The "First Papers of Surrealism" auction/exhibition is held at the Whitelaw Reid mansion on Madison Avenue. (DK170)

Installation view of First Papers of Surrealism exhibition, showing Marcel Duchamp’s His Twine 1942

(Photographer: John D. Schiff) (Gift to the Philadelphia Museum of Art of Jacqueline, Paul and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother Alexina Duchamp)

The exhibition was organized by André Breton and Marcel Duchamp for the Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies and held at the private Whitelaw Reid Mansion on Madison Avenue. (RM137/BA332) Duchamp strung five miles of string between the temporary partitions on which the art was hung. Children were brought in to play amongst the string. One of the children was Milton Avery's daughter, March Avery who recalled, "We were encouraged to run about and I remember feeling somewhat uncomfortable both because I didn't think it was proper behaviour for an opening and also because I sensed that some of the guests were of the same opinion." (SS227) Although the reviewer for The New Yorker magazine praised Masson's Meditation on an Oakleaf and Matta's The Earth Is a Man ("scintillating"), he wasn't so crazy about Duchamp's string, writing "String is boring. So is Surrealism. It has grown tired, tedious and a little repetitive. The earlier work is better." (SS227)

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

... it was Marcel Duchamp who was asked to devise a plan to camouflage the elaborate decor and gilded moldings of the reception rooms, as well as to develop a concept for the catalogue... Duchamp's first response to the challenge was to visit the Seligmann's tranquil farm in Sugar Loaf, where he took up a gun and fired five shots at the stone wall of the nineteenth-century barn. Since it would have been uncharacteristic of Duchamp to have owned a lethal weapon, it is conceivable that he used the gun that Seligmann kept for protection in his isolated farmhouse. If so it was very likely the same gun from which the bullet was fired that killed Kurt Seligmann twenty years later, not 200 feet from that same barn wall. Duchamp photographed the section of the barn wall with the bullet marks and used the photograph on the front cover of the catalogue for 'First Papers,' punching out five bullet holes....

The exhibition included work by Picasso, Arp, Miro, Ernst, Dali, Kay Sage, Kurt Seligmann, Leonora Carrington, Esteban Frances, Matta, Joseph Cornell, David Hare, Robert Motherwell, Barbara Reis, Lawrence Vail (who was Peggy Guggenheim's husband prior to her marriage to Max Ernst), . (SS230) William Baziotes (The Butterflies of Leonardo da Vinci (SS359))and Hedda Stern. (BA332) Paintings included Matta's The Earth Is a Man; Max Ernst's Surrealism and Painting (aka Surrealism Paints a Painting) and La Planète affolée; Gordon Onslow Ford's First Five Horizons (since lost): and André Masson's There Is No Finished World and Meditation on an Oakleaf. (SS229) Jackson Pollock was also asked to participate but declined. According to David Hare, "Jackson didn't like the Surrealists because he thought they were anti-American. And the Surrealists didn't like him because they expected to be courted all the time. Jackson wouldn't court them at all." (JP123)

Masson later (1958) commented on Meditation on an Oakleaf: "In New England there are oak trees three times larger than here [France], the leaves also. The weeds are three times larger than here and the insects gigantic, for there is an astonishing fauna and it remains very wild 250 kilometres from New York... so I put a wildcat in my painting." (SS227)

Time magazine ["Inheritors of Chaos," November 2, 1942]:

Organized by Pioneer Surrealist André Breton for the benefit of French prisoners of war, it [the exhibition]... had a striking installation: a cat's cradle consisting of miles of string woven all through one exhibition room. As an added attraction a number of schoolboys were employed to play catch with footballs over the labyrinth.

Among the show's 105 exhibits, including dolls, idols, ceremonial masks by American Indian primitives, was work by painters Masson, Delvaux, Chagall, Tanguy, Magritte, Vail, Hirshfield. Of those canvases faintly visible behind the 7-ft.-high string cobweb was a huge new Freudian nightmare by Surrealist Ernst. Painted specially for the exhibition, Surrealism & Painting depicted a nest of multicolored bosomy birds, from whose naked, writhing limbs a semihuman arm emerged to paint its creator's conception of the disorderly universe. In the next room hung early canvases by de Chirico; also three recent Picassos, one of which, Les Femmes au Bord de la Mer, dwarfed, by its sheer creative power, every other painting in the show.

The catalogue included a foreword by Sidney Janis and an an essay by Robert Allerton Parker praising eccentrics and visionaries and, according to Sawin, "fourteen pages devoted to myth... ending with the Grand Transparents, illustrated with David Hare's composite photograph of a figure half consumed in flames. The chosen myths were pagan, Christian, medieval and contemporary, and they were represented by old engravings and photographs and twentieth-century paintings in the Surrealists' favourite process of analogy." (SS225-26)

October 19, 1942: Art Exhibition for the Benefit of Armenian War Relief at the Art Students' League.

The works in the exhibition were auctioned with the proceeds going to support the Armenian Tank Division who were fighting with Russia against Hitler. Arshile Gorky contributed three paintings - The Head, Summertime in Sochi and Black Sea. Later he heard that the organizer of the exhibition had bought the paintings for himself for five dollars. Gorky was outraged and told him he would donate the $15 himself if the pictures were returned to him but the organizer refused. (B334-335)

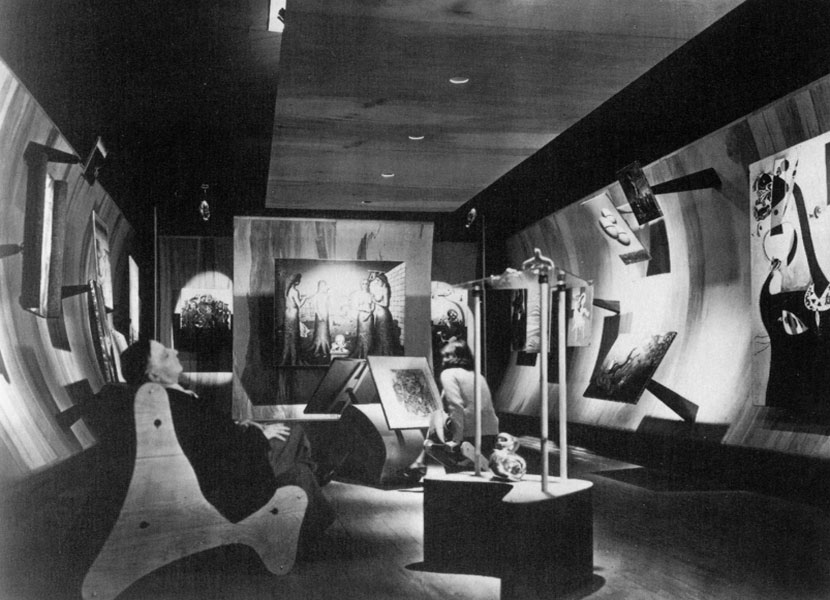

October 20 1942: Peggy Guggenheim opens Art of this Century.

Frederick Keisler seated in the foreground of Peggy Guggenheim's gallery, Art of This Century, 1942

(Photo: Berenice Abbott)

André Breton helped select the works for the opening show. Only one American was included - John Ferren. Guggenheim's second show "Exhibition by 31 Women", which opened January 5, 1943, was an exhibition of work by women artists, including Djuna Barnes, Carrienton, Buffie Johnson, Kahlo, Gypsy Rose Lee (a self-portrait), Louise Nevelson, Meret Oppenheim, I. Rice Pereira, Kay Sage, Hedda Sterne, Dorothea Tanning, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and others. (MD240) Later solo shows at the gallery would include William Baziotes, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko. (RO181/DK170)

Time magazine ["Inheritors of Chaos," November 2, 1942]:

As art lovers emerged from dimmed-out Manhattan streets, they encountered a blinding white light. "That's day," said the patroness of Surrealism, Peggy Guggenheim, shielding her eyes from a mass of blue-white electric bulbs. "Isn't it awful?" "Day" illuminated a "painting library" (a large room enclosed in a sinuous purple tarpaulin), where art lovers were invited to sit on narrow, legless, armless rockers, and by turning unframed canvases hung from triangular columns, study the exhibits from any angle they desired.

Such is the entry of a new museum opened last week for the benefit of the Red Cross by jet-haired Miss Guggenheim, wife of Painter Max Ernst. Under the name Art of This Century, Miss Guggenheim's four-roomed gallery (30 West 57th) is to be a permanent show. All owned by herself, the collection of 171 exhibits (14 by husband Ernst) is reputed to be the biggest of its kind.

Beyond the painting library, gallery-goers enter a kind of artistic Coney Island. Here are shadow boxes, peepholes, in one of which, by raising a handle, is revealed a brilliantly lighted canvas by Swiss Painter Paul Klee. Another peep show, manipulated by turning a huge ship's wheel, shows a rotating exhibit of reproductions of all the works, including a miniature toilet for MEN, by screwball Surrealist Marcel Duchamp.

Beyond these gadgets mankind swarms into what seems to be a decorated subway. There spectators gaze at large canvases by England's Leonora Carrington, Spain's Miro, Chile's Matta, all their works unframed, suspended in the air from wooden arms protruding from concave plywood walls. Every two minutes, while onlookers enjoy the spectacle, a roar as of an approaching train is heard, lights go out on one side of the gallery, pop on at the other.

This installation is the creation of diminutive, Austrian-born Scenic Designer Frederick J. Kiesler, director of the laboratory of the School of Architecture at Columbia University. Says he, making everything plain: 'We, the inheritors of chaos, must be the architects of a new unity.'"

The gallery, Located on the top two floors (previously tailor shops) of 30 West 57th Street, opened at 8:00 pm on October 20th. Admission was $1.00 with the proceeds going to the American Red Cross. Mark Rothko attended the opening. (RO179) The press release for the gallery described it as a "research laboratory for new ideas" to "serve the future instead of recording the past." (PP319-20)

The Guggenheim collection was exhibited in three gallery spaces in the main gallery: the "Automatic Gallery," the "Surrealist Gallery" and the "Abstract Gallery." The temporary exhibitions were shown in the "Daylight Gallery" with natural light coming in from the large windows overlooking 57th Street. (RO180)

November 1942: Franz Kline and wife move to 23 Christopher Street (top floor). (FK177)

November 1942: Howard Putzel writes to Onslow Ford about Jackson Pollock.

In November 1942 Howard Putzel, who advised Peggy Guggenheim on her collection, wrote to Onslow Ford, "I have discovered an American genius... Matta speaks very enthusiastically about Pollock's work and so, surprisingly, does Soby." (SS337/DK205)

December 9, 1942 - January 24, 1943: "Twentieth Century Portraits" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

The exhibition included Arshile Gorky's My Sister, Akho. According to his wife, Agnes, Gorky purposefully gave it an earlier date of 1917 "because he didn't want it hung next to the boys in the back room." (BA337) After his death it was renamed Portrait of Ahko.

December 7, 1942 - February 22, 1943: "Artists for Victory" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The show consisted of 1,418 works by contemporary American artists. Jackson Pollock exhibited The Flame (c.1934-38) (PP320) The first prize for painting went to American regionalist John Stuart Curry for Wisconsin Landscape. (RO164) Other prize winners included Alexander Calder, Jack Levine, Marsden Hartley, Jacob Lawrence, Philip Evergood and Frank Kleinholz.

The exhibition generated two protest exhibitions which Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb and other Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors members participated in: "American Modern Artists" (aka "Four American Artists") at the Riverside Museum January 17 to February 27, 1943 (which is also referred to as "and "New York Artist - Painters" February 13 to February 27, 1943. In "New York Artist - Painters" Rothko exhibited his works based on myths: A Last Supper, The Eagle and the Hare, Iphigenia and the Sea and The Omen of the Eagle. In American Modern Artists he exhibited Seascape, Seated Figure, Sculptor and Nude. Barnett Newman wrote text for the catalogues. (RO164-65)

Mark Rothko [re: The Omen of the Eagle]:

The picture deals not with the particular anecdote, but rather with the Spirit of Myth, which is generic to all myths at all times. It involves a pantheism in which man, bird, beast and tree - the Known as well as the Knowable - merge into a single tragic idea. (RO166)

December 28, 1942 - January 11, 1943: "Adolph Gottlieb: Paintings" at the Artists Gallery.

The exhibition was the first solo exhibition of his Pictographs.