Trash

(Produced by Andy Warhol; Directed by Paul Morrissey)

Essay by Gary Comenas

page one

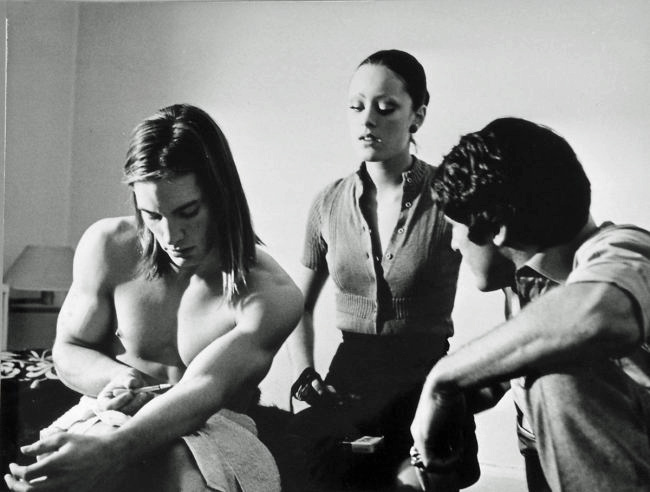

Joe Dallesandro shooting up in front of Jane Forth and Bruce Pecheur in Trash - publicity still from the press kit of the German distributor, Constantin-Film. (The cover of the press kit billed the film as Andy Warhol's Trash)

103 minutes - Director, story, screenplay, photography, camera operator: Paul Morrissey - Producer: Andy Warhol - Editor: Jed Johnson, Paul Morrissey - Song: "Mama Look at Me Now" by Joe Saggarino, sung by Geri Miller - Sound: Jed Johnson (Note: Vincent Fremont was also part of the crew, holding the boom mike, helping to carry equipment and shooting stills with his Kodak Instamatic. Fremont also recalls that he thinks "Bobby Dallesandro, Joe's brother drove a VW van to haul the equipment, etc." (Email December 11, 2020)

Cast: Joe Dallesandro (Joe) - Holly Woodlawn (Holly) - Jane Forth (Jane) - Michael Sklar (welfare investigator) - Geri Miller (go-go dancer) - Andrea Feldman (LSD girl) - Johnny Putnam (boy from Yonkers) - Bruce Pecheur (Jane's husband) - Diane Bodlewski (Holly's sister) - Bob Dallesandro (boy on street) (FPM136/gc)

-----

Although Trash is often characterised as a Warhol film, it was actually Paul Morrissey who directed it. Morrissey's films are often confused with the films that Warhol directed because the Morrissey films are usually advertised with Warhol given top billing, as in Andy Warhol's Trash. Warhol produced (i.e. paid for) the Morrissey films and it was not uncommon at the time for the producer to receive top billing. Dino de Laurentis usually got top billing of the films he produced, such as Barbarella (1968) and Serpico (1973) yet they were directed by somebody else - Roger Vadim in the case of Barbarella and Sidney Lumet in the case of Serpico. Irwin Allen was the producer of The Towering Inferno (1974), and other disaster films, yet it was his name that got top building - not the director's. Having Warhol's name emblazoned at the top of advertising helped to sell the films.

Some film scholars have attempted to draw a dividing line between Warhol's 'art' films and his narrative films and in some cases have made the Morrissey films the dividing line. Film scholar David James considers this distinction in his essay "The Producer as Author."

David James ("The Producer as Author," in Michael O'Pray, Andy Warhol Film Factory (London: BFI publishing, 1989), pp. 136-7 - orig. publ. in Wide Angle, vol. 7, no. 3, 1985):

Warhol's career as a film-maker contains so many abrupt lurches into new directions and shifts to different scales of production that description of it in terms of a single expressive urgency is as difficult as organizing it in terms of standard generic categories. But all the singular achievements as well as the desultory, incomplete projects that lie between the silent rising and fallings of John Giorno's abdomen in Sleep in 1963 and the logo "Presented by Andy Warhol" splashed across the ads for the Carlo Ponti Company's production of Frankenstein in 1974, do refer to a trajectory of which Warhol's own distinction between "the period where we made movies just to make them" and a subsequent decision to make "feature length movies that regular theaters would want to show" [Popism] is as just an anatomy as any. Though the caesural pivot that both joins and separates the autotelic art and the commercial enterprises is difficult to place - does it lie after Empire (1964)? - or The Chelsea Girls (1966)? - or Lonesome Cowboys (1967)? - or Trash (1970)? - certainly a distinction between an early Warhol and a late Warhol can be elaborated in both formal and biographical terms. It corresponds to increasingly sophisticated technological investments, the shift from private Factory showings to public exhibition, and an engagement with the grammar of industrial cinema, with scripting, fiction and narrative as commonly understood.

The gist of David James' argument is clear although some of the details are fuzzy. Even Warhol's "art" films were often shown in "public exhibition" at the various cinemas used by Jonas Mekas as cinematheques. (see "Jonas Mekas and the Film-Makers' Cinematheques.") James goes on to ask whether the "trajectory" toward a narrative cinema represents a degradation of Warhol's filmic qualities from an artistic level or whether, "Warhol came of age as a film-maker... around the time that his collaboration with Paul Morrissey began." [As quoted from John Russell Taylor in Directors and Directions: Cinema for the Seventies (NY: Hill and Wang, 1975) p. 137]

Morrissey's films are certainly more entertaining to watch for most people than watching the Empire State Building on screen for eight hours (see Empire) but are they "art?" No. But they're not meant to be. Warhol was an artist. Morrissey was a film director. It was to Paul's advantage that his films be entertaining because entertainment meant commercial success. According to Bob Colacello, Paul wasn't on a salary but got 50% of "any movie profits." (BC35)

Trash wasn't Morrissey's first film for Warhol, but it may have been one of his most successful - both domestically and internationally. One reason for its success was the performance of Holly Woodlawn - her first time in a Warhol/Morrissey film.

According to Holly, her first scene in Trash was filmed in Paul Morrissey's apartment "on a cool Saturday afternoon in 1969." (HW133) By that time Warhol's Blue Movie had premiered, been seized by the police (in August 1969) and had been ruled obscene (in September 1969). (See Blue Movie.) The previous film that Morrissey had directed for Warhol, Flesh, had opened the previous year in September 1968. (Warhol is credited as the director of Blue Movie, Paul Morrissey as the director of Flesh). According to Joe Dallesandro's biographer, Michael Ferguson, "Trash, as the title eventually became known, was shot mostly on Saturday afternoons over three weekends in October 1969, with a final scene picked up on a Saturday the following spring." (JOE90)

Holly was a friend of the drag queens who had appeared in Flesh - Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling. Holly appeared in a play written by Curtis - Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit in September 1969. Curtis was also supposed to be in the production but was kicked out after numerous arguments with the director, John Vaccaro.

Leee Childers (photographer):

While Jackie Curtis was in rehearsals for Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit, a play she had written and was starring in, and which was being dircted by John Vaccaro, things got a little out of hand. John Vaccaro was a very difficult man to work with because he used anger to draw a performance out of a person. And Jackie was a speed freak who was extremely paranoid and accusatory - the slightest thing would throw her into a frenzy. So she and John fought constantly, and he eventually took all her clothes and ripped them to shreds, threw her shoes at her, fired her, and kicked her down the stairs, which he was famous for doing, and Ruby Lynn Rainer took over the title role. (PM110)

According to legend, Holly first came to Paul Morrissey's attention after Heaven Grand had opened and she was interviewed for an underground magazine, claiming to be a Warhol superstar.

Holly Woodlawn:

In September 1969, Heaven Grand in Amber Orbit, opened on Forty-third Street in a small funeral-home-turned theater. I'd spend hours preparing for my role as Cukoo the Bird Girl, who was featured in the chorus as a Moon Reindeer Girl... The Moon Reindeer Girls' opening number was a song called "Antlers" which was sung to the tune of "There's Nothing Like a Dame" from the musical South Pacific... Rodgers and Hammerstein it wasn't, but we were written up in Newsweek! Also, a writer by the name of John Heys did a feature on me for an underground news rag. My first big interview. Well, I couldn't say I was a nobody, so I took the opportunity to use the media to my best advantage and lied through my teeth. I told him that I was a Warhol Superstar and they ran the story with some shmaltzy Art Noveau photos taken by Leee Childers...

When Paul Morrissey saw the issue with my face plastered on the page and giving an interview as to what it was like being a Warhol Superstar, he was amused." (HW131)

According to Holly in a later interview, the "underground news rag" was Gay Power. (MZ) Gay Power was the first bi-monthly gay newspaper, founded by John Heys in August 1969. Heys was an actor in Charles Ludlam's Ridiculous Theatrical Company and had worked with a number of artists, including Jackie Curtis. Warhol star Taylor Mead was a regular contributor to the magazine which ran for 24 issues. Heys was the editor until August 1970. (JEH)

Paul Morrissey backs up Holly's account in his introduction to her autobiography, A Low Life in High Heels: the Holly Woodlawn Story, except that he notes that Warhol was already aware of Holly as someone who had tried to charge a camera to his account in a photography store.

Paul Morrissey:

When I cast Holly in the film Trash, I had never met him. Someone had brought to my attention an article in some throwaway underground newspaper that discussed in great detail Holly's success as a major star of Andy Warhol productions. Since Holly had never been in any of the films and I had never even met him, this brazen lie must have appealed to my comic sense. I simply had a hunch that here was some kind of "character" or personality. Although Andy pointed out that Holly was someone who had tried to rob him by charging an expensive camera to his account, the combination of lying and larceny only increased my curiousity. (HWix)

Holly had accompanied a friend from Max's who had tried to charge an expensive camera to Warhol's account, telling the shop clerks that Hollly was Viva. When the clerk went to verify the charge, they ran out of the shop. (HW130)

Most of the other cast members of Trash had either been in one of Paul or Warhol's previous films or were regulars at Max's. Joe Dallesandro had appeared in both Loves of Ondine and Flesh. Geri Miller, the stripper, was in Flesh. Andrea Feldman had appeared in Imitation of life and was a regular at Max's Kansas City. According to Joe Dallesandro's biographer, Michael Ferguson, Jane Forth was a sixteen year old friend of Fred Hughes who replaced Patti D'Arbanville (from Flesh) for her role as the rich girl in Trash.

Michael Ferguson (Joe Dallesandro: Warhol Superstar: Underground Film Icon: Actor (NY: Open Road Media, 2015), p. 152 - 153

The role was originally meant for Patti D'Arbanville, who neglected to show up on the day of shooting. When Morrissey called her to ask where she was - that they were all waiting - he was told that she decided she couldn't be in a movie with such a title and that director Roger Vadim was going to make her a star. Strapped, and already having the West End apartment for the day's shoot, Morrissey took the suggestion of soundman Jed Johnson who remembered Jane and thought she might be good. Morrissey called and Jane was on her way.

When Jane was asked by the English photographer, David Bailey, how she first met Warhol for a TV documentary that was broadcast in the UK in 1973, she said that she had first met the artist when she was "fifteen."

Jane Forth (Bailey On Andy Warhol, Associated Television (ATV) for the ITV TV network, transcript):

... I met Andy when I was fifteen. I came up to the Factory and knew someone who worked at the Factory and er they brought me up here and I went out to dinner with him and I was scared to death of him. Also the very first, first time I met him was, I went with someone over to his house to borrow a black leather jacket for some photographs and everyone said Andy Warhol and Andy Warhol I had never heard of him before, I didn't know who he was. I went up there and I kept thinking well if this Andy Warhol's famous he must be very handsome with dark hair and everything else so and I went up there and there was this little skinny man sitting on the end of the bed with white hair and I said, "This is Andy Warhol?" And that is how I met him. [grammatical errors retained]

It's unknown how the actor who plays Jane's husband, Bruce Pecheur, got involved in the production. In the film Jane and Bruce's apartment is broken into by a intruder played by Joe Dallesandro. This would actually happen to Bruce in real life in 1973. An intruder broke into the apartment he was living in with his wife and child. Pecheur attempted to fight the intruder and both ended up dying in the struggle. By the time of his death on August 16, 1973, Pecheur had appeared in a few additional minor films (none by Warhol) and was also an uncredited party guest in the film The Way We Were, featuring Barbra Streisand. (IMDB)

Trash opened in New York on October 5, 1970 at the Cinema II to good reviews. But the actor in the film who got most of the press attention - Holly Woodlawn - was apparently in jail at the time. As the legend goes, she had been jailed for forging cheques while impersonating a French diplomat's wife. She would later deny the story in the New York Times but then repeat it in subsequent interviews and in her autobiography.

According to an interview for a short film made during her 2002 appearance at the Cannes Festival, Holly had a friend who was subleasing an apartment from a French diplomat and his wife who were in France. Holly and her friend found the wife's passport and stuck a photo of Holly (dressed in loads of feathers) taken by Jack Mitchell into the passport. Holly has never explained, however, how the the wife got to France without her passport. Apparently, it was the artist Larry Rivers who got Holly out on bail after the reviews of Trash came out.

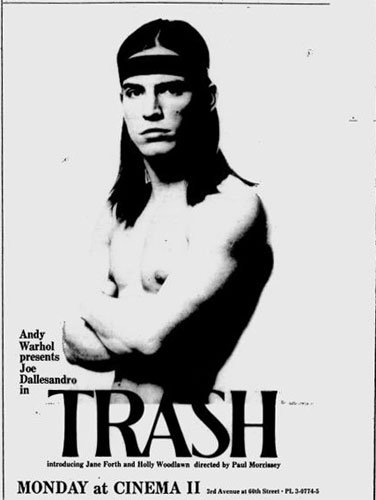

Ad in the October 1, 1970 issue of the Village Voice for the opening of Trash

One of Trash's best reviews was written by Bob Colacello for the Village Voice. Colacello was already writing for Inter/VIEW magazine at the time, but his Voice review of Trash was praised by Warhol when Colacello was promoted from being a contributor to Inter/View to the editor of the magazine.

Trash is bascially the story of a junkie (Joe) who can't get it up, despite numerous attempts by his co-stars - including Geri Miller (the stripper), Holly (who he lives with), Andrea Feldman (an acid-freak) and Jane Forth (a wealthy woman whose apartment he breaks into).

In his review of the film, Colacello characterised these (attempted) sexual exploits as a "metasexual Pilgrim's Progress" where "Drugged stoicism played off against sexual fanatacism emerges as the major thematic motif of the film, in much the same way as the contrast between agnostic stoicism and religious fanaticism dominates [Bunuel's] The Milky Way."

Colacello described Dallesandro's backside as a "Greco-Roman ass" in his review and Holly Woodlawn was "an amphetamined El Greco." Comparing stripper Geri Miller to Holly, he notes that that a "reference to Our Lady of the Flowers cannot be avoided." The scene where acid-freak Andrea says that she wants to be a cock, apparently elevated the film to a "social document."

Bob Colacello ("Film: Trash," The Village Voice, October 9, 1970, p. 58):

At one point he [Joe] is picked up by a phony rich acid freak who, licking her own breasts, screams, "I'd like to be a cock, one big cock!" - a gross, grotesque, but nonethess genuine plea for release from the respressive rigidity of sexual roles, from the corrosive power struggles of human relationships. In a highly unreal, yet utter realistic manner, Trash, thus becomes a social document.

Colacello recalls the response of Warhol and Morrissey to his review in his book Holy Terror, Andy Warhol Close Up. He had gone to Warhol's offices to show the then editor of inter/VIEW magazine, Soren Agenoux, the final version of a Bertolucci interview that he had written for the magazine.

Bob Colacello (Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (NY: Harper Collins, 1990), p. 36 - 37):

Several rewrites later [of the Bertolucci interview], I headed downtown to Union Square. The inter/VIEW office was not only locked but chained. Soren Agenoux [editor] and his cherubic assistant, Jeremy Dixon, were always there in the early afternoon - where were they? I went down to the sixth floor to see if they were there and found Andy eating lunch at his Deco desk. "Is Soren around?" I asked.

"Oh, uh, something happened," said Andy vaguely. "I think Paul wants to talk to you. Gee, your Trash review in the Voice was really great."

Paul also liked it. "A little intellectual," he told me, "but I liked the line about Holly looking like 'an amphetamined El Greco.' And Joe's 'Greco-Roman-ass' - that was pretty funny. And it was very perceptive of you to make the comparison with Our Lady of the Flowers - 'cause if anybody's more Catholic than Genet, it's us. We're not as perverse, though."

Then he got down to buisiness. Would I like to be editor of inter/VIEW? Soren had been let go. Paul explained that Andy and he had been "too busy" to read the last three issues, "and then the other day, I started reading them and I realized Soren was putting out a silly scandal sheet."

"But I don't know anything about editing a magazine, " I said, stunned. "And I've still got another semester to go at Columbia."

Paul assured me that "putting together a magazine isn't that big a deal. "You just slap some pretty pictures down on the page and you and your friends from school could probably do most of the interviews." (BC36-37)

Vincent Canby reviewed Trash for the New York Times and, as with other journalists, singled out Holly Woodlawn's performance in his review: "Holly Woodlawn, especially, is something to behold, a comic book Mother Courage who fancies herself as Marlene Dietrich but sounds more often like a Phil Silvers." (Vincent Canby, "Movie Review: Trash (1970) Film: Andy Warhol's 'Trash' Arrives: Heroin Addict's Life Is Theme of Film Techniques of 30's on View at Cinema II," New York Times, October 6, 1970)

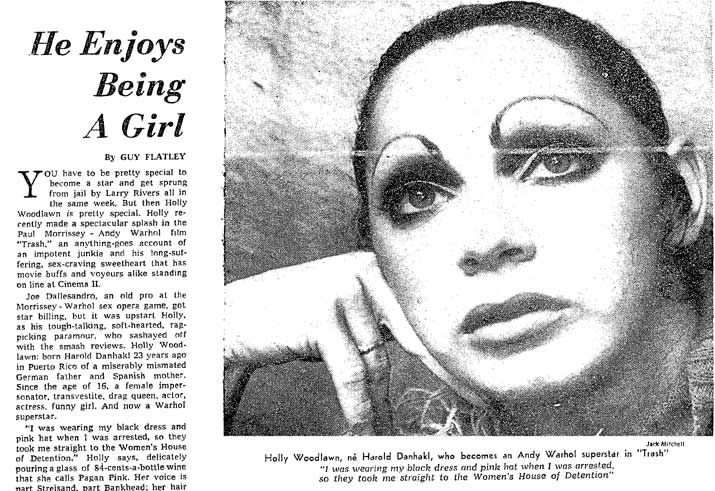

This was followed up by an interview with Holly in the November 15th issue of the Times which included a large photo by Jack Mitchell. In was during that interview that she denied that the story about impersonating a diplomat's wife was true.

Guy Flately "He Enjoys Being a Girl," New York Times, November 15, 1970

Guy Flately ("He Enjoys Being a Girl," The New York Times, November 15, 1970):

But the question remains: how on earthy had Holly got in? Was it true, as rumoured, that she had been posing as the wife of the French ambassador to the U.N. blithely cashing checks and running up impressive charge accounts in her name?...

"Absurd!" pooh-poohs Holly. "Why, I don't even speak French! What do they think I was doing, anyway - running around town saying, 'Excusez-moi, darling, I have here this great big check which you will please cash immediately? I might just as well have gone up to the guard at the U.N. and said, "I am the Australian queen; let me in right away, since I must dash up to the gift shop and hock my tiara." The truth is I don't remember exactly how it all happpened, because I was drunk. Zonked. Bombed out of my mind. I recall sitting there in the lobby of the U.N. looking out at the fountain going splish, splash, splish, splash, when all of a sudden this man and woman came walking over to me in a big hurry... and before I knew it I was down at the Women's House of Detention.

In the account in her autobiography, A Low Life in High Heels, Holly refers to the diplomat's wife as Mme. Chardonet (Holly's favourite wine was Chardonnay) and says it was her friend George who put her up to the crime. She refers to the friend who was subleasing the diplomat's flat as "Chumley" and says that she was arraigned for a "grand larceny" of $2,000 (equal to about $12,000 today). But she never mentions how she finally evaded the charge and no diplomats have ever been identified.