Gene Swenson, Andy Warhol and the Personality of the Artist cont.

by Gary Comenas (December 2016)

Page 3

Gene Swenson made numerous contributions to the art world before and after "The Other Tradition" essay and exhibition mentioned by Bill. Warhol star Gregory Battcock, gave a run down of some of Swenson's activities in the an article, "The Art Critic as Social Reformer," Art in America, September-October 1971 which was reprinted in the exhibition catalogue for "Gene Swenson: Retrospective for a Critic" which took place after his death. The exhibition ran from October 24 to December 5, 1971. The catalogue included essays by Battcock, Lucy Lippard, Ann Wilson and James Rosenquist.

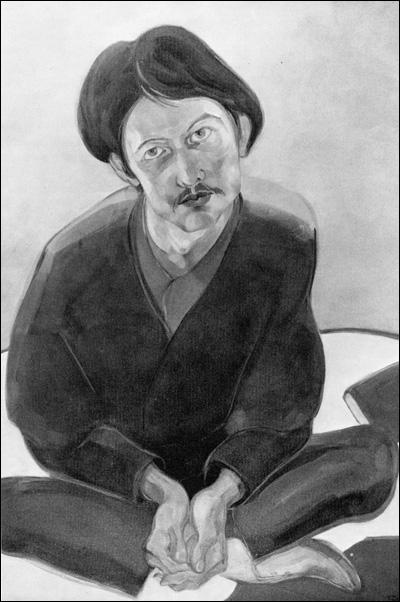

Portrait of Gene Swenson, 1968 by Karl Stuechlen (GS11)

Gregory Battcock:

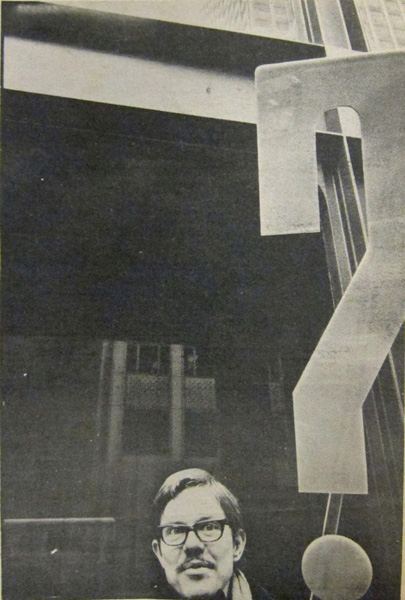

Swenson attempted to bring contemporary art into the mainstream of political and social protest... His actions first became gossip, then legend: his trip to the United Nations to obtain international citizenship, his shouting matches with art dealers and publishers, his picketing of the Museum of Modern Art in the winter of 1968-9 carrying a huge question mark.

He had been in and out of Bellevue and many thought him crazy... Perhaps it was his dealings with the Museum of Modern Art, for which he organized an exhibition called "Art in the Mirror" in 1967 [November 22, 1966 - February 6, 1967], that focused his attention on art museums and their effect on broader social and cultural issues. It wasn't long before Swenson dared to link up the management of the museum with American foreign policy and the Vietnam War. In 1968 he became something of a latter-day Diogenes by picketing the Museum every day from eleven to two for a period of several weeks while carrying, for a sign, a large question mark...

At one point Swenson issued a printed statement announcing that he would perform an "act of melodrama" at the museum. He arrived an an opening dressed in a paper vest bearing the words, "VIRTUE IS ITS OWN REWARD," and carrying a tin beggar's cup. He intended his gesture to illustrate the "intellectual poverty" of the art world...

Swenson's gestures, writings and political stance confused and alarmed many people. His challenges to respected art-world figures (Thomas Hoving, Clement Greenberg, Henry Geldzahler), his linking of the prestigious Castelli Gallery with capitalist exploitation, his attacks on the Museum of Modern Art - all identified targets that had hitherto been immune from social and political scrutiny...

Though eventually he had difficulty in publishing his work, Swenson continued to articulate his ideas. A number of them appeared in the now defunct New York Free Press. "An Art Critic's Farewell Address" is a curious sensitive document that isn't really a farewell address at all, but another plea for ethical reevaluation of modern esthetics, containing "personal experiences that were anathema to the orthodoxies of current art-writing. his last published piece, "From the International Liberation Front" was printed in the Art Workers Coalition "Open Hearing" volume in 1969. It is a manifesto touching on art, politics, the war in Asia and revolution. When he rose to read the document at the historic Open Hearing at the School of Visual Arts on April 10, 1969, Swenson was still working on it...

Swenson's large and passionately held reformist views give his own single-handed attempts to accomplish them a degree a pathos. Yet his brief career was exemplary in it's pursuit of them at any cost - and the cost in friends, stability and financial security was great. When Swenson died, many of felt as though we had lost our conscience.

Jill Johnston recalled Swenson's madness in an article she wrote for the Village Voice in which she interviewed R.D. Laing and also dealt with her own mental problems. [Errors of grammar and capitalization are Johnston's own.]

Jill Johnston ("A stray case of normality," Village Voice, December 7, 1972, p. 39):

... I had a friend, gene swenson who went on an intergalactic journey in his own space ship. I've forgotten the details, but I know he went, possibly the reason nobody believed him was that it wasn't written up in the papers. The splashdown occurred on the roof of his tenement on 4th street and the recovery operation team was the local precinct police and the check-up took place at the hospital. I suppose the astronauts get the psychological test treatment too. And you remember originally they were locked up in a trailer or something on the carrier after the frogmen pulled them out of water.

She continues by noting that the analogy with the astronauts "breaks down at the point where you might say gene was on a more dangerous trip since he had to improvise his own guide and preparation system. I remember him for example bending intently over my radio one afternoon listening for 'number signals.' She writes that he took three "intergalactic" trips into madness before he setttled down and took the medicine that was prescribed him.

Jill Johnston:

He came back three times, and after the third time the Medical Inquisition Recovery Team and all the rest of their frogmen at least convinced the guy that he was a "case." He was ready then to take their tranquilizers forever and get a nice nine to five job filing something and wear a suit and a tie and go to a shrink very often regularly to keep himself straight. The last thing that happened was he biologically died in a car crash in kansas with his mother. At 35 he was still going back to kansas to see his crazy parents who were never his most avid supporters. I'm sure I wasn't the only one who kept saying don't go back home gene, there's even that famous book titled you can't go home again, but who were we but an extended family still telling him what not to do.

Johnston has no "idea what the complex dynamic fuel system was that launched gene on his trips, who could ever know what that is, much less the chief passenger, but I do know that his life situation was basically untenable to himself and that a journey to 'other regions' was in order and that as a one way ticket to bellevue he became a two-time loser every trip he took. No credibility anywhere." She also recalls a visit to her apartment by Swenson and Ann who brought along a "cardboard mobile of the galaxy."

Jill Johnston:

One day he came over to my loft with ann wilson who brought a tape recorder and a cardboard mobile of the galaxy she strung up form the ceiling the idea being gene was going to recount his journey but we got into kansas and the family instead somehow and somebody said what's that got to do with the big trip and I said oh it's all the same thing but I didn't know what I was talking about and even if I did we didn't know what to do really. We didn't know what to do about ourselves. The journey solution was no big deal. If you couldn't come back and seriously change the conditions of the place you found it necessary to leave Nor roles for the mad.

Jill also wrote an obituary in the Village Voice for Swenson when he died. A copy of it is here. She also included his death (and life) in her autobiography in which she also mentions Ann Wilson and William S. Wilson. She begins by noting several of the art world events she attended in New York around the same time that Ann and Gene came into her life in 1968.

Gene Swenson with his giant question mark outside the Museum of Modern Art

Jill Johnston (Autobiography in Search of a Father Volume II: Paper Daughter (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 207-209, 214-220):

That March of '68, I found an opportunity to announce my new persona. The date was the 25th, the opening of the Dada-surrealist show at the Museum of Modern Art. Where some art-rebel types demonstrated outside the museum, others, like myself, challenged authority from within. If there was any real difference, it was that I had no idea that this was what I was doing. Costume, in my case, was everything. Highly attuned to the event as a showcase, I went out and rented a tuxedo and top hat for twenty-five dollars... My appearance felt like a debut. I hardly looked at the art, which was my art; I was much more interested in how I looked myself - standing around drinking, laughing, and basking in the spectacle I hoped or imagined I was creating...

She also attended a "Destruction of Art" symposium four days before the MoMA opening and a Steve Paxton dance concert.

Just four days before this Dada opening, I had witnessed Charlotte Moorman at the "Destruction in Art" symposium use a violin to bash in the head of the man who had tried to stop her performance. By the time I appeared in a rented tuxedo at MOMA, my piece about this ("Over His Dead Body") had been printed. A week earlier, my Hermann Nitsch-inspired piece had appeared. On March 22 Steve Paxton presented an evening that I thought was sublime, in particular a "dance" called Satisfyin' Lover for thirty-two people, who walked across the performing area (a gymnasium) one after the other in regular street clothes. The Yip-In at Grand Central happened the same night.

Johnston writes that it was around the time of those events that she met Ann and Gene and that "both had also been to Bellevue," as had Jill.

Around that time I became acquainted with two people who bridged the worlds of art and politics and who would mean a great deal to me in the months to come. One of them had organized the demonstration outside MOMA the night of the Dada-surrealist opening; the other lived down the street from me, at the big, sprawling intersection of Canal Street and the Bowery where the Manhattan Bridge lies.

Both had also been to Bellevue. Of the two, Ann Wilson, who lived down the street, had not gone crazy exactly but had tried to commit suicide by consuming quantities of pills. That was in late August '65, her stay at Bellevue preceding mine by several weeks...

According to Jill, Ann first met the artist, Ray Johnson, before marrying Bill Wilson whom she then left for Gene Swenson. Jill describes Swenson as "an active homosexual."

Ann had come to New York about 1954 from Pittsburgh, where she had studied art at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon), a class behind Andy Warhol. She said she had gotten off the Greyhound bus in Manhattan with a bunch of framed paintings and was met by Ray Johnson, who took her directly to America's leading gallery, the Janis... Within two years she was living in a loft building on Coenties Slip also occupied by Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly. Nearby were Leonore Tawney, Robert Indiana, Jack Youngerman, John Chamberlain, Jasper Johns, and Rauschenberg. Ann left the Slip in 1960 to marry Bill Wilson [William S. Wilson], college professor, critic, writer, and son of a well-known art-world character called May Wilson. By the time I met Ann she was quite a well-known art-world character herself. With Bill she had twin daughters and a son, losing her standing with the artists by becoming a mother. She then lost her standing as a mother by falling in love with Gene Swenson ("a romantic escape," she has described it, "from the harshness and domestic responsibility of marriage") and running away from home. With Gene her standing was precarious because Gene was mostly homosexual...

Gene was an active homosexual, and during this period, he had a boyfriend called Harry... Sometime during '67 Gene cracked up and went to Bellevue. I believe that event radicalized him. Unlike myself, he found an immediate target for his rage. That year he conducted a prolonged one-man picket outside the Museum of Modern Art, made a revolutionary speech on the steps of the Leo Castelli gallery, was arrested for charging a police barricade at an antiwar demonstration, delivered an address in front of the courthouse in which he was to be tried (and later acquitted) and wrote something called "A Critic's Farewell Address," openly declaring his disaffection from the New York art art world. At the beginning of '68 he staged a series of solo protest events in front of MOMA, which banned him from entering the place. Later he organized a big group demonstration against the Dada-surrealist show the night of the opening I so blithely crashed in a tuxedo. Gene found it "absurd and obscene for official recognition to defuse the revolutionary ideals that lay behind these movements." He took out small ads in the Voice reading, "MOMA is dead. Dada is dead. Celebrate! Mausoleum of Modern Art" or "Artists and poets! Do your thing! Join les Enfants du Parody in the Transformation! Tea and black tie optional" or "Dedicated to the lost but not forgotten spirit of Dada and surrealism. Their historical bodies are now embalmed and on view at MOMA." I couldn't relate to it. I was inside the museum, "doing my thing," but thought of it in no way politically. Politics to me still meant a bunch of brutish people in Washington who ran something called a government which had nothing to do with me. I had been sympathetic to artists like Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine who made funky work in great poverty downtown and said they hated the museums; but I observed that within no time they were showing in the best galleries uptown and soon seemed to have no objection to being shown in the museums...

So who was Gene Swenson? A good friend of his, a painter called Basil King, said he was a man who had been sent out of Kansas to be a genius. That says practically everything. Gene's father was a man who pumped gas in a gas station, his mother a schoolteacher, very ambitious for her son - a D.H. Lawrence sort of mother. He went through Yale and arrived in New York in 1956, becoming an art critic and historian. He lived in the same tenement on Fourth Street for eleven years, got a master's degree at N.Y.U., wrote reviews for the same magazine I did (Art News), and contributed essays to other periodicals, in particular about the art and artists that came to be known as pop. I first remember seeing him at a pop art symposium at MOMA in 1963 (presided over by a panel including Cage, Rauschenberg, Duchamp, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Roger Shattuck), speaking from the audience in a agitated defensively authoritative manner. The museum was perhaps already his bête noire. Gene was a champion of the avant-garde like myself, his territory a lot less circumscribed than mine, its stakes hardly his alone to claim. When I met him, I was struck by a blaring incongruity in his appearance. His clean-cut, attractive, blue-eyed, all-American, Ivy League, charcoal-suit look was belied by his intense gaze - on edge, expectant, uncool, mischievous, wild. He had an air of permanently shocked naiveté, or of "signaling through the flames" from behind his glasses, an extreme idealism contradicted by some personal knowledge of brutality, which in fact he openly disclosed, perhaps boasted of, in the form of his S&M interests. Gene was a guy who never really made it out of Kansas - his prestigious Eastern education had not prepared him for the world. he remained like a girl, untutored in the rules of the game. Plucked out of his class, plopped down in a fast competitive city where art has always been an instrument of wealth and power, he found himself out of his depth. He hated to see that deals were made and things were not pure, that art was not an ideal pursuit in itself. Once he understood that art served capitalist ends and was not just a beautiful autonomous tradition, he conceived a program to make it serve other interests, revolutionary ones that characterized the sixties and his own unfolding life. He wanted power himself but opposed it at large; his real program seemed to be to set an example by self-destruction. He would go after the power, then undermine any base or foothold he managed to get. The axis of change for him in the sixties must have a a show he organized at the Modern in November '66 called "Art in the Mirror." A long essay he had intended to write for the exhibition was cut short by an attack of acute appendicitis.

The following spring he went mad, and the rest of his career, until August '69 when he died, was marked by increasing political radicalization and intermittent bouts of insanity. Besides the Modern (which, I feel certain, had courted and rejected him), his other special targets were Leo Castelli and Henry Geldzahler, who had been a schoolmate of Gene's at Yale. Geldzahler, golden boy of art, ensconced as curator at the Met, represented everything Gene both wanted and hated. The Gene I knew was this madman, either flipped right out, creating bizarre scenes (throwing eggs out his sixth-floor window onto the tops of cop cars, driving chariots or rocket ships naked on the roof of his building) or politically suicidal, waging this war singlehandedly against the sort of establishment that would be the last to see any serious uprising on the part of its peons, the artists. But I saw Gene in quiescent moods also: withdrawn, fragile, transparent, recovering from one collision or another with the hospitals or the police. I had a welter of feelings about him, none of them very consciously connected with the aspects of my life that mirrored his. One day he visited me in my loft and scared me by his mediumistic intensity and his "mission" of listening to my radio, his ear right against the speaker, to pick up the "number signals" for his rocket-machine assignment or operation or whatever it was. When not on his earthly political missions, he was soaring away visiting other planets and settling galactical disputes. He was definitely trying to get away. Nobody else I ever hear of had a Pan Am reservation to the moon. One time when he was sane and sober Ann brought him over to my loft with a mobile of our planetary system, the kind you might hang over a child's crib. And I thought that if we could help him re-create one of his trips by hanging up the mobile and stimulating his memory and associations, I could then translate it all in family terms. Luckily, nothing came of it, because Gene didn't want to play. He held forth on art and politics as usual, enthralling Ann and boring me...

I never heard him say anything about his parents. The men in the art world never said such things. Why think about home, from which art and New York represented the great escape? But Gene was obviously thinking about home - his last "mission" was a car crash with his mother on a Kansas highway, an "accident at the cross-roads." His father survived them, and an older brother who was a colonel in the Marines. Gene was thirty-five (the same age incidentally, as poet Frank O'Hara when he died in 1961 in a car accident on Fire Island). Compared to Ann, I was barely affected by Gene's death. I had lost one of my crazies, but crazies were everywhere at the end of the sixties, and Gene (along with Ann) had been angry or jealous of me for my freedom to write irrelevant (i.e., unpolitical) things week after week in a paper that had become successful. The last time I saw him he was yelling at me, the substance of which I don't remember, behind a violently extended arm and forefinger. Possibly it was because I had advised him not to go to Kansas. I rarely minded my own business, and I assumed that whatever worked for me would work for anybody else. I had disavowed my mother, therefore Gene would do well to do likewise. Gene had been seeing a shrink who told him he should get a nine-to-five job, the same message Ann got from hers and that I had gotten from mine in '66 at St. Vincent's. The presumption underlying these "therapies" was that our lives in New York had led us astray, our parents had been right about us, and a regular job would demonstrate a certain remorse and the desire of reform and to recapture our parents' values. In '67 Ann wrote in her journal: "Gene was sick in bed with a cold, furious with his Dr. because he had expected Gene to accept a 9-5 job. That's such a problem of anger and despair for us. This business of our art not being commercial coin and hence our time our gifts not respected in this pragmatic society..." After he died, she wrote, "I am carrying [his] books down six tenement flights of stairs under the unsparing scrutiny of the bare light bulb on each landing - the only author who corresponds in any way to this life of those I carry is Céline... the hopes of a life of art in endless garbage-strewn tenements. No wonder that Gene's life was bitter and maddened by dreams of unreal success." Though I could not know it then, Gene was an important addition to my small pantheon of male heroes: child-men, mother's sons, eternal boys, founding on the constructs of their fathers, ever proving that society moves by dissent as well as conformity. (JJO207-209, 214-220)

When I showed Johnston's quote to Bill Wilson, he responded "too many sorrows in Jill's riff to respond right away to your own interior trembles - two wise people judged Gene to be in love or in lust for me... I was a real toad in his imaginary garden. The fatal accident with his mother driving reads as suicide-murder, within which killing him is killing her, and killing her is killing him. (March 15, 2014). He later clarified, "Gene has a weird position in my romantic husbandly history. A pair of psychiatrists I consulted about handling the three children decided that Gene had been in love with me as a married father of children, with then the displacement onto Ann. Once, when a waiter asked Gene what he wanted, he pointed toward the waiter and responded "You!" Studying the rather few but intense pages brings back Pittsburgh and misadventures. A moment came when Gene's entertaining madness ceased to be funny, yet did not become trivial. Dying in a car crash with his mother offers dimensions of tragedy in a modern mode - an accident without discoveries (as approaches toward truth) and without reversals (which would peel back appearances to reveal concealed truths). (Email December 13, 2014)

Gene Swenson died in August 1969. David Bourdon recalls, "With tragic irony, Gene Swenson died at age thirty-five in a traffic collision in August 1969. He and his mother were driving along an interstate highway in western Kansas - they were second in a line of cars - when, ahead of them, a tractor-trailer suddenly jackknifed, killing everybody in the first three automobiles." Jill Johnston died September 18, 2010. William S. Wilson died February 1, 2016. Ann Wilson is still alive.

William S. Wilson (Email August 12, 2005):

Gene's interviews were sadistic; he fucked over the artists, I think hoping to inspire someone to rough him up. He was brilliant and amusingly crazy, until he was boringly crazy, repetitive with flat obsessions. Still, his dying was horrible, & many people read it as a suicide, somehow, his mother driving. No one can possibly know. A huge figure in my life, not for a moment missed by me, but he had a large part in my story...

[end]